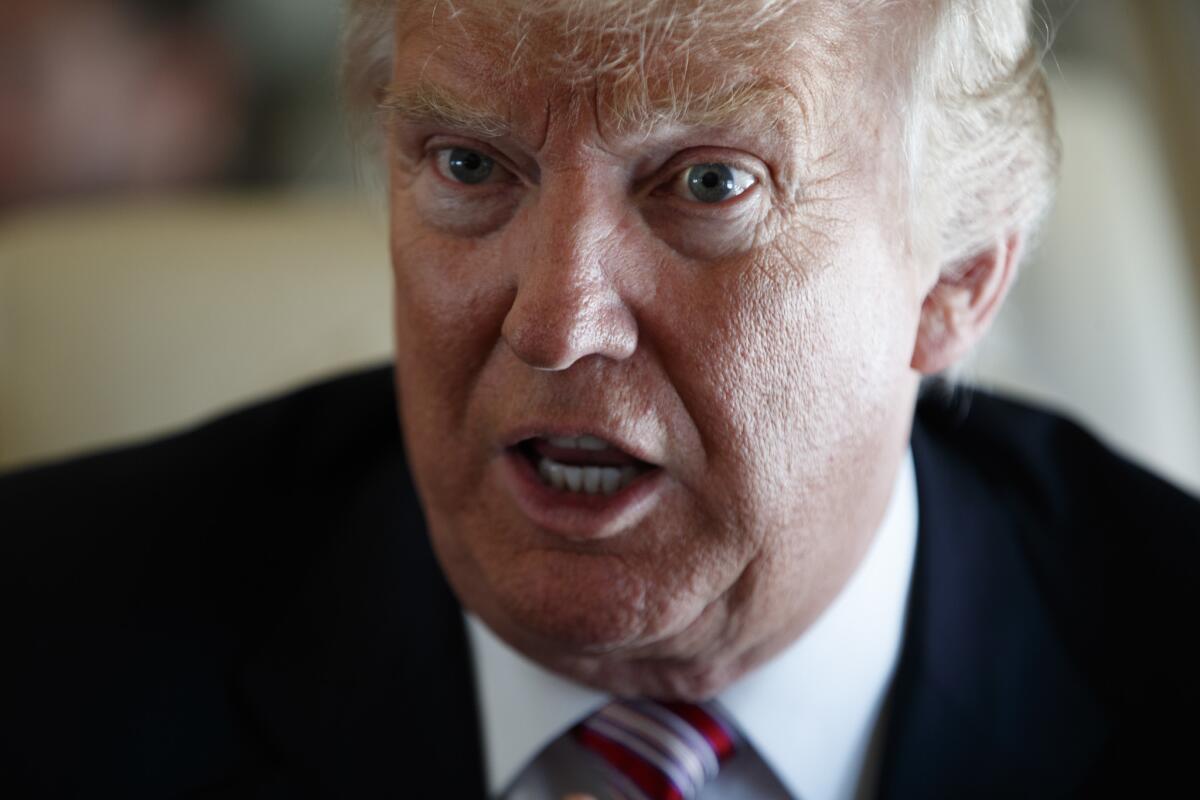

‘Believe me’: People say Trump’s language is affecting political discourse ‘bigly’

Trumpisms: A look at one of Trump’s most common speech patterns. Say it, repeat it, say it again. Read more >>

Reporting from Washington — Of all the rules of politics that Donald Trump has broken in his run for the White House, his way with words may top the list.

Perhaps not since Sarah Palin gave Americans her tossed-word salads has a candidate’s speech pattern been so debated, celebrated and mocked.

But Trump is more than just a free-style rambler. Experts say he employs a very deliberate, effective communications approach unlike any other presidential candidate in memory.

The Trumpisms — “Believe me,” “People say,” “Sad!” — have become so well known they are the subject of spoofs. But like a savvy salesman or break-through advertising campaign, Trump’s techniques carry a quiet power.

Here’s a breakdown of Trump-speak.

The art of the insult

Little Marco. Lyin’ Ted. Crooked Hillary. Even in the rough-and-tumble world of presidential politics, Trump has taken the art of the insult to a new level.

Trump’s name-calling may sound like simple bullying. But labeling his opponents with cutting nicknames also creates simple frames — catch phrases — that stick in voters’ minds, often because they reinforce existing perceptions.

George Lakoff, a linguistics professor at UC Berkeley who has written extensively about political speech, says studies show that 98% of thought is unconscious. Creating those nicknames is a way to make the broader message resonate with voters long after the rallies have ended — like a good advertising jingle.

“Even if he loses the election, Trump will have changed the brains of millions of Americans, with future consequences,” Lakoff writes on his blog.

As a businessman, Trump learned that speaking in an irreverent, shock-jock manner often won him free media attention. Now some Trump supporters are cheering that same willingness to give voice to politically incorrect opinions that they may secretly share, but would never say out loud.

Among the most controversial examples were his description of Mexican immigrants as “rapists” and his pondering of whether the Muslim mother of a U.S. Army captain killed in Iraq wasn’t “allowed” to speak alongside her husband at the Democratic convention.

“He has this great talent for, any time there’s a lull, he goes and grabs up all the attention again,” said Barton Swaim, author of “The Speechwriter: A Brief Education in Politics.” “I’m out of the business of predicting how he won’t go to the next level.”

Say it. Repeat it. Say it again.

It’s a crescendo of almost every Trump rally, the call-and-response moment when Trump promises to build a “great wall” along the Southern border. “Who’s going to pay for it?” he asks. “Mexico!” the crowd answers.

Of course the Mexican president has said unequivocally that his country will not be paying for Trump’s wall. But that hardly matters. In Trump’s world, repeating something makes it seem true, even when it’s demonstrably not.

For example, Trump continues to insist that he warned against entering the 2003 Iraq War, despite a 2002 audio clip of him voicing support. He has repeatedly claimed to have watched TV footage of Muslims in New Jersey cheering on 9/11, despite no evidence of such an event.

He often repeats false claims that inner-city crime is at record highs or that neighbors of the San Bernardino terrorists saw bomb-making materials in their apartment but did not report it.

“The more a word is heard, the more the circuit is activated and the stronger it gets, and so the easier it is to fire again,” Lakoff writes. “Trump repeats. Win. Win. Win. We’re gonna win so much you’ll get tired of winning.’”

‘Believe me’

With this two-word imperative, Trump draws voters in, hoping to inspire confidence, create intimacy and form a bond of trust with voters. It’s a connection that has often eluded Hillary Clinton, with her multi-point solutions to the nation’s problems.

He often uses it to reassure his audience that he has the answers to the nation’s problems or to allay doubts about his abilities.

“I know more about ISIS than the generals do. Believe me.”

“We are going to get rid of the criminals,” he says about his immigration plan, “and it’s going to happen within one hour after I take office.… Believe me.”

Experts say it plays to listeners’ desire for a strong leader with easy solutions. Trump becomes like someone who is huddling close to tell a secret, or like a salesman giving you the inside scoop on a deal.

But Jennifer M. Sclafani, associate teaching professor in linguistics at Georgetown University and author of the forthcoming book “Talking Donald Trump: A Sociolinguistic Study of Style, Metadiscourse, and Political Identity,” said “what people interpret from this particular command is ambiguous.”

That makes “believe me” a double-edged sword for Trump, she said. For Trump’s supporters, it reinforces what they already believe about Trump. But skeptics “are likely to interpret this phrase as coming from an untrustworthy candidate who needs to command his audience to believe him, because he is naturally unbelievable.”

People say…

One of Trump’s signature constructs comes when he’s about to say something controversial — even conspiratorial — but wants to lean on others to do it.

“Many people are saying that the Iranians killed the scientist who helped the U.S. because of Hillary Clinton’s hacked emails,” Trump tweeted last month, though such a conspiracy theory was easily debunked.

After the Orlando nightclub shooting, Trump implied President Obama did not want to stop terrorists, but tried to take cover by putting the offensive remark in the mouths of others. “There are a lot of people that think maybe he doesn’t want to get it,” Trump said on the “Today” show. “A lot of people think maybe he doesn’t want to know about it.”

The “people say” construct allows him to float an idea without taking full ownership or blame.

“What he’s doing is making use of principles that people use all day every day — to get across ideas that are not true,” Lakoff said.

Trump dismissed criticism that he linked rival Sen. Ted Cruz’s father to President Kennedy’s assassination, insisting he was only pointing to a National Enquirer story about the elder Cruz allegedly meeting with Lee Harvey Oswald.

This Trump style, too, has found a home on social media. One band in Texas tweeted recently: “Many people are saying our next album will heal the sick and end all war. It’s just what many people are saying.”

Never having to say you’re sorry

Trump rarely issues a public apology, no matter how wrong he is proven to be or how strong the public pressure.

He insisted he did not “regret anything” about his attacks on the Gold Star Khan family. He refused to back down from his claims that an American-born judge overseeing the Trump University fraud lawsuit could not be fair due to his Mexican heritage.

He won’t apologize for leading the so-called “birther” movement questioning Obama’s citizenship, even though advisors say it might help him win over African American voters.

“I like not to regret anything,” he told radio host Don Imus earlier this year when asked if he regretted questioning whether Sen. John McCain of Arizona, captured during the Vietnam War, should be considered a war hero.

His one and only public expression of regret came last month, but even that was vague and included the verbal architecture of an I’m-sorry-if-you-were-offended apology.

“Sometimes, in the heat of debate and speaking on a multitude of issues, you don’t choose the right words or you say the wrong thing,” Trump told a crowd in North Carolina. “I have done that, and I regret it, particularly where it may have caused personal pain.”

Keep it simple

One of Trump’s biggest strengths with voters has been his ability to speak plainly and to simplify — some would say oversimplify — complex issues.

Build the wall to stop illegal immigration. Bring back coal and steel-manufacturing jobs. Defeat the terrorists “so fast your head will spin.” He convinces supporters that simple solutions would work and intractable problems linger only because of the “stupidity” of U.S. leaders.

In contrast, Clinton is often criticized for sounding too scripted, too poll-tested, too detail-oriented. Obama, too, seemed sometimes paralyzed by the complexity of challenges.

His tweeting is a prime example, mastering the ability to boil down talking points and policy views to 140 characters or less.

Lakoff says that Trump’s simple solutions appeal to those who see direct cause-effect of problems, but not those who view the world in more complex terms.

Clinton is “very careful about what she says. But when she does that, that means she’s not engaging in normal everyday conversation,” Lakoff said. “He’s using all of these mechanisms: It’s what you hear, not what you say. He has just taken it to the extremes and run with it.”

Say it ‘bigly’

Trump’s plans are “tremendous.” His victories “HUUUGE.” Exaggeration and hyperbole are hallmarks of Trump’s communication style.

His financial disclosure statement used all capital letters to boast his wealth: “TEN BILLION DOLLARS.” Though he is the first presidential candidate in decades to refuse to release his tax returns, he insisted recently that he has “released the most extensive financial review of anybody in the history of politics.”

The Clinton Foundation is not merely a scandal, according to Trump, “it’s the most corrupt enterprise in political history.”

And then there’s “bigly.”

“We’re going to win bigly,” Trump said in a victory address in Indiana after becoming the presumptive nominee.

Much has been said and written about “bigly” — if it’s a word and if it’s what Trump is saying. Dictionaries say “bigly” exists in one of those old-timey ways that hasn’t been in fashion for 100 years or so.

But Trump’s spokeswoman, Hope Hicks, told Slate magazine it’s not “bigly” at all. Trump, she said, is saying, “big league.”

Like much of Trump’s speech, it seems open for interpretation.

Twitter: @LisaMascaro

MORE ELECTION NEWS

‘I’m just lost.’ Voters find it hard to commit to Clinton or Trump

How much do presidents and candidates need to tell the public about their health?

Democratic and Republican voters are further apart than they’ve been in a generation. Here’s why

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.