Trump’s big, early lead in Facebook ads deeply worries Democratic strategists

Reporting from Washington — Almost every time voters who lean toward President Trump visit Facebook, they get deluged with invitations to his rallies or pleas to support his immigration policies: That’s no surprise — the platform was central to his victorious 2016 campaign.

What they probably don’t expect is that the Trump campaign also follows them to more distant corners of the internet — placing ads that supporters see on YouTube channels like Epic Wildlife, Physiques of Greatness and BroScienceLife, even the liberal site Daily Kos. The campaign’s willingness to spend money on such sites may or may not pay political dividends, but its willingness to gamble points to something bigger that unnerves the Democratic Party’s top digital thinkers.

“His campaign is testing everything,” said Shomik Dutta, a veteran of Barack Obama’s two campaigns and partner at Higher Ground Labs, an incubator for progressive political tech. “No one on the Democratic side is even coming close yet. It should be gravely concerning.”

Trump is using the advantage of incumbency, a huge pile of campaign cash and a clear path to his party’s nomination to build a digital operation unmatched by anything Democrats have. His campaign is testing all manner of iterations, algorithms and data-mining techniques — from the color of the buttons it uses on fundraising pitches to the audiences it targets with short videos of his speeches.

By the time Democrats pick a nominee, some of the party’s top digital strategists warn, Trump will have built a self-feeding machine that grows smarter by the day. His campaign has run thousands of iterations of Facebook ads — tens of thousands by some counts — sending data on response rates and other metrics gleaned from the platform to software that perpetually fine-tunes the campaign messages.

As with most campaign tactics, no one knows for sure how much difference the flood of money and advertising on Facebook might make. Despite all the testing of how people respond to specific messages, even the richest political campaigns don’t spend much money on rigorously researching the ultimate question of what, if anything, sways voters, especially with an incumbent who inspires such strong feelings — positive and negative — as Trump.

Still, the central fact of the 2016 election likely will remain true for 2020: Trump’s victory margin in key states was so slim that just a handful of voters staying home or showing up could make the difference.

The main goal of the Facebook ad effort is raising money. But as it widens its base of small donors, Trump’s campaign also gains contact information for activists and accumulates insights into what sells to the narrow group of persuadable voters Trump potentially could win over.

That could mean anything from learning that Trump’s thumbs-up and pointing gestures inspire more campaign donations — a fact — to which messages most encourage voters to surrender phone numbers and demographic data.

For a planned kickoff rally in Orlando, Fla., the campaign posted a variety of Facebook ads — showing Trump head on, from the side, from the corner. He’s wearing a red tie, a striped tie and no tie at all. There is a range of musical styles and graphics, including one version that intersperses palm trees and an alligator wearing a red Make America Great Again hat along with more casual images of Trump pointing his index fingers toward the camera.

Though most of the ads are geared toward promoting Trump’s personality and immigration policies or lambasting the “fake news,” Trump is also testing very narrowly targeted messages. In April, he touted a rare legislative achievement with crossover appeal — a law passed in the fall that reduced some federal criminal sentences — in Southern states with large black populations such as Florida, Georgia and North Carolina. Trump is deeply unpopular with most minority voters, but lower-than-expected turnout of black voters in Detroit and Milwaukee was among the reasons for Hillary Clinton’s narrow losses in Michigan and Wisconsin in 2016.

Other ads cite Trump’s efforts at nuclear negotiations with North Korea and the confirmation of Supreme Court Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh. A heavy focus on the “fake news” media helps insulate Trump from reporting of facts that undercut his case, including the lack of progress on nuclear talks, controversies about Kavanaugh’s past or Trump’s failure to rewrite the nation’s immigration laws.

One of his most used advertising themes, building a wall on the southern border, asks supporters to sign a petition “to show all Republican Senators a list of the many American voters that will NOT be happy if a wall isn’t built.”

Trump has also begun testing attacks on Democratic opponents, using “sleepy Joe” to target former Vice President Joe Biden in several ads while targeting Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts on gun control.

Each of the messages could return in the general election, using information gathered now.

Chris Lehane, a longtime Democratic strategist who heads global policy and public affairs at Airbnb, said that Trump “is running a true 21st century campaign…. The more data you collect, the smarter your flywheel gets. They are doing this with precision.”

The Trump campaign’s marketing and advertising director, Gary Coby, compares the campaign’s approach to high-frequency trading on Wall Street, constantly buying and selling to see which ads bring the most value.

“Every month we’re testing on other channels,” he said. It is a turnabout from Trump’s last campaign, he said, when “we didn’t have the luxury of time to test and explore.”

Democrats are online too, but in a way that does much less to boost the party’s prospects next year. Locked in a competitive primary season, their online targets are donors in liberal areas and voters in a handful of early primary states — people already inclined to vote Democratic located mostly in regions not crucial to retaking the White House. Trump’s messaging is far more likely to pop up on screens in such up-for-grabs states as Michigan, Ohio or Arizona.

For Democrats, “this couldn’t be further from a general election strategy,” said Andrew Bleeker, a leading digital strategist for Obama, Clinton and other Democratic candidates who runs the firm Bully Pulpit. Trump and his allies, meanwhile, are making inroads in the places that will matter in 2020, he said.

Subscribe to the Los Angeles Times 2020 election calendar »

The question is whether Democrats will be able to catch up when they have a nominee.

“They’re going to be so far behind in terms of just sheer volume of testing that they’re going to have to rely on just standard practices rather than what’s tested,” said Josh Canter, a Republican digital consultant based in Austin, Texas, who is not affiliated with Trump.

Trump’s campaign has spent $15.5 million on digital ads so far this year, more than any other political group or candidate, according to data from Santa Monica-based Pathmatics, which detected purchases as small as the one on BroScienceLife. But it’s not just Trump. Other top spenders include a website called Conservative Buzz ($8.8 million), the right-leaning Judicial Watch ($3.7 million) and the Republican National Committee ($2.6 million).

The Democrats to crack the top 10: Sen. Bernie Sanders ($5.5 million), Sen. Elizabeth Warren ($3.4 million) and Gov. Jay Inslee ($2.4 million). Planned Parenthood Action Fund ($2.8 million) is the only liberal group on the list.

In the backdrop of this digital surge, strategists for both Democrats and Republicans continue to debate how much campaign money should be shifted away from television and into digital. Trump has become a pioneer, with plans to use as much as half the campaign’s advertising dollars online. The ratio impresses many of the digital campaigners on the left who cut their teeth with Obama.

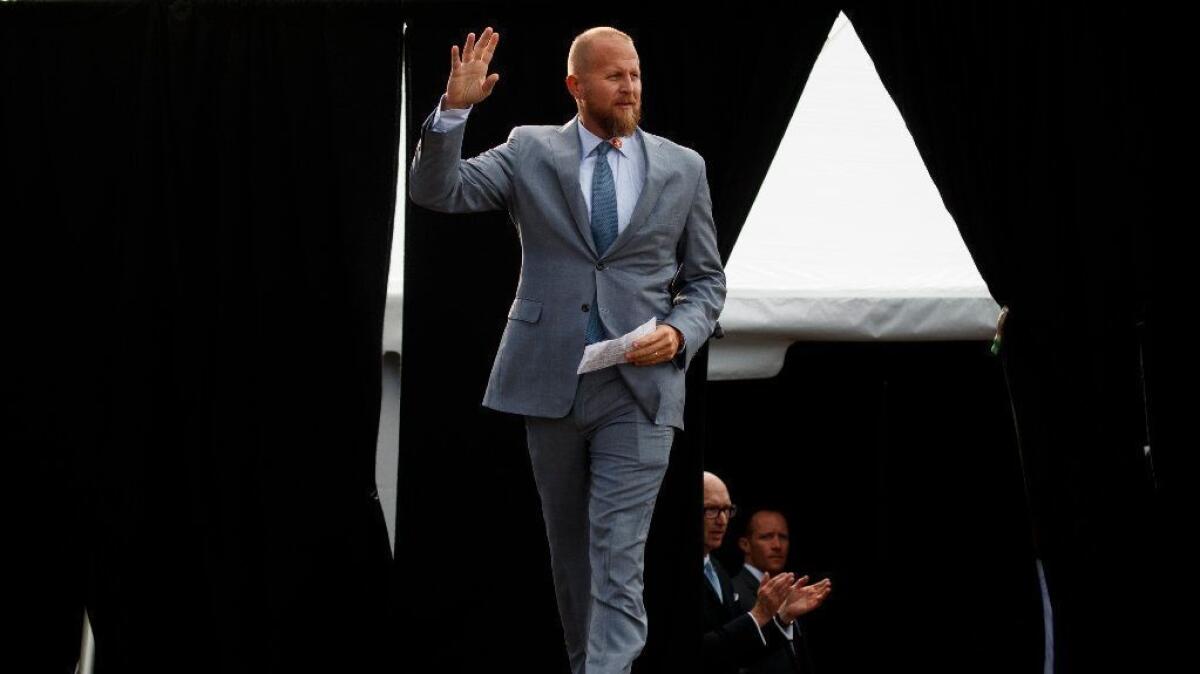

But Trump’s digital mastermind didn’t find his way into the job through the usual path of Stanford hack-a-thons or venture capital-driven startups. Brad Parscale, a tall Texan with a long beard and a faux-hawk hairdo, had been designing websites for Trump’s winery and other projects before he was tapped to run his 2016 digital campaign operation and then manage the entire campaign for 2020. His renegade style, disdain for the establishment and Trump-world street cred have made him a campaign trail attraction, sought out for local television interviews and appearances on rally stages.

Parscale’s aptitude for Facebook is believed to have helped Trump reach significantly more voters per dollar than Democrats, whose content does not tend to keep users as engaged on the platform as long. Facebook algorithms reward advertisers who persuade users to stick around.

Much of the effort seems targeted at fundraising. But getting Facebook users to pitch in $10 or $20 is just the start.

“By getting these people to donate, they have email addresses,” said Patrick Ruffini, a Republican digital strategist. “They have their cellphone number if they’ve been to a rally. They have lots of different ways to communicate with their base other than Facebook, and that’s where any incumbent is going to have an advantage.”

But Ruffini points out that Clinton appeared to have all the campaign advantages in 2016 before Trump built a Facebook campaign from scratch.

“If somebody catches on — like a Buttigieg,” he said, referring to South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg, “or if Warren catches on further … she’s going to have the chance to do what Trump did.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.