Loud and angry, protesters turn congressional town halls into must-see political TV

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell spoke to his constituents as protests were held outside the venue Feb. 22 in Jeffersontown, Ky.

Reporting from Mariposa, Ca. — They came by the hundreds, in big cities and rural hamlets, to heckle, plead, badger and, in some instances, to protest the protests themselves.

Congress is in recess this week, and a citizenry suddenly spurred to action used the opportunity to let their returning lawmakers know just how they feel about the tempestuous last month in Washington.

“Winners make policy and losers go home,” a taunting Mitch McConnell, the Republican Senate leader, told an invitation-only gathering in his home state of Kentucky, as about 1,000 protesters gathered outside.

Not exactly.

The town hall meeting, a throwback to a time of more intimate connection, has become a political organizing tool in the social media age — a piece of performance theater and a worldwide stage.

Obamacare, immigration, environmental regulation, Social Security, Russian meddling in the 2016 election and Trump, Trump, Trump — all poured forth this week in the form of questions, loudly and heatedly.

The raucous gatherings have been the mirror image of the clamorous sessions that birthed the tea party movement early in President Obama’s term, a conservative opposition that tormented him — and sometimes the GOP establishment — throughout his eight years in office.

About 900 people showed up in an auditorium at the fairground in Mariposa, a small tourist way station on the road to Yosemite, for Elk Grove Republican Rep. Tom McClintock’s town hall. It was more than 10 times the usual attendance and better than a third of the local population.

The conservative lawmaker drew a burst of applause by dispensing with opening remarks. “This evening is yours,” McClintock said, “so have at it.”

And the audience did, for more than double the hour he had scheduled.

He was grilled about repealing the Affordable Care Act and promising the replacement would be an even better healthcare plan. “What’s the plan?” voices cried out. “Show us a bill!”

He was mocked for questioning the science behind global warming. “The planet has been warming on and off since the last Ice Age,” McClintock said to hoots and laughter.

He was ridiculed for likening President Trump to his unbridled predecessors Andrew Jackson and Theodore Roosevelt, and taunted for downplaying the contacts between Trump allies and the Russian government.

“I think you will find votes I have cast have the support of the vast majority of people in this district,” said McClintock, who was easily reelected in November to a fifth term. “The moment they don’t, there’ll be somebody else standing here.”

“Good idea!” someone shouted.

But even some of the harshest questions were prefaced with thanks for McClintock’s willingness to show up early and stay late.

“God bless all of you for being here,” he said at one point after a woman in the audience said the huge turnout was a show of resistance to Trump. (In fact, about a third or so of the crowd appeared strongly supportive of the president.)

For Rep. Buddy Carter, a two-term GOP lawmaker representing a staunchly conservative stretch of coastal Georgia, the boos began as soon as he tried to present plans to replace the current healthcare law.

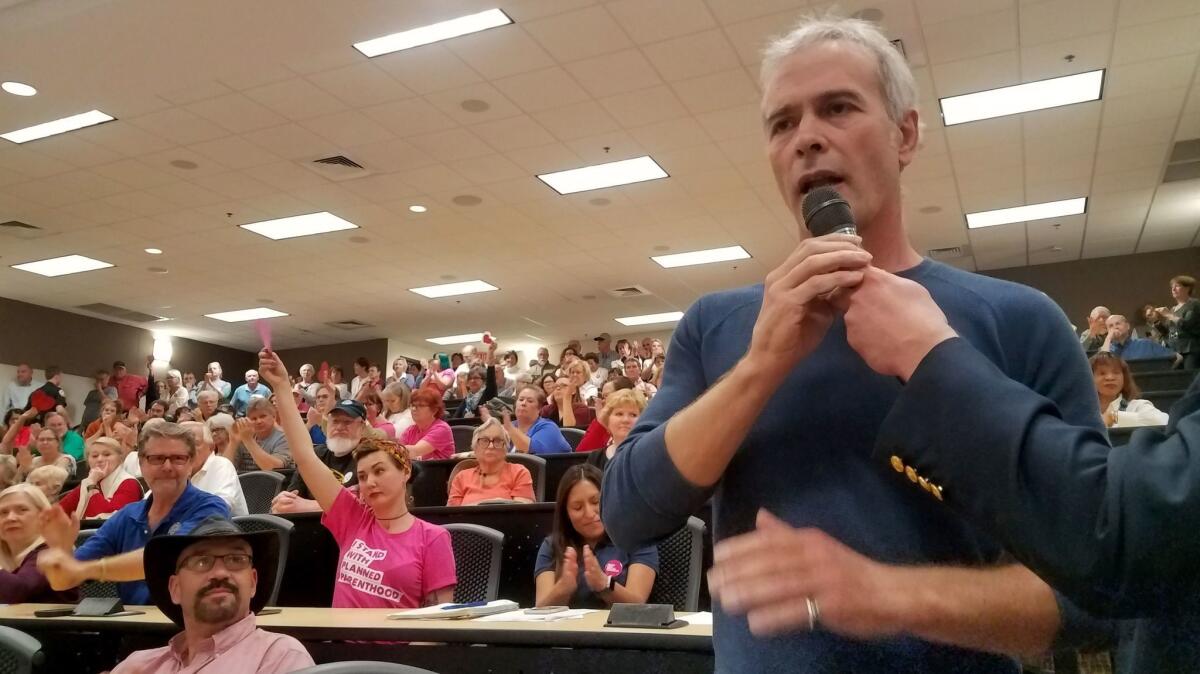

More than 300 people, many wearing Planned Parenthood T-shirts and waving pink and purple paper hearts, squeezed into a college auditorium in Savannah for the standing-room-only event. Outside, scores more chanted, “Let us in!”

The crowd erupted in jeers as Carter displayed a slide titled “Broken Obamacare Promises.”

“Affordable Care Act!” a chorus of voices yelled, objecting to the use of the GOP nickname for Obama’s signature healthcare law.

“You know about the promises and you know about the reality,” Carter told constituents, saying that annual healthcare premiums had risen $4,300 for the average family.

“Look, folks, Obamacare is collapsing,” Carter said.

“You collapsed it!” a man in the audience hollered back, and the crowd roared.

An earlier round of town halls this month produced a number of screaming spectacles, prompting many Republican lawmakers to scrub their latest recess schedules of any such face-to-face encounters.

Some preferred to conduct safer “telephonic town halls,” where participants were screened and no cameras threatened to turn confrontation into the Internet’s next big viral moment.

In central Florida, Republican Rep. Dennis A. Ross learned that being reelected a third time with 58% of the vote did not guarantee a friendly crowd.

Appearing before about 250 people and a comfort dog, Ross dodged questions, catcalls and boos before exiting just shy of his scheduled hour.

The last question had three parts: about the expense to taxpayers of Trump’s frequent Florida visits, about his seeming fondness for Russia and about the president’s still-unseen tax returns.

“This is the first anyone has brought that to my attention,” Ross said of the reported $10 million it cost to shuttle Trump for three trips between Washington and his Palm Beach resort.

The boos were so hearty and long that the rest of Ross’ answer could not be heard, though one word was audible — “Hawaii,” likely a reference to where Obama vacationed.

Then the congressman quickly hustled out the back door to a chant of “Do your job!” — the unofficial rallying cry for those who consider the Republican-run Congress too pliant toward the president.

Some skittish GOP lawmakers skipped meeting with constituents altogether; in California, the liberal group Indivisible circulated milk cartons bearing the word “Missing” and the face of Republican Rep. Paul Cook, a three-term congressman from the southeastern desert.

Democratic lawmakers were far more eager to lend a platform to critics of the president and GOP lawmakers. For some people, the gatherings were akin to therapy, or a group session on translating grief into action.

“Sign people up; get people involved,” Rep. Tony Cardenas exhorted a crowd of 300 crammed into an auditorium at the Cesar E. Chavez Learning Academies in Los Angeles’ heavily Democratic San Fernando Valley.

“Register people to vote; beg other people who are citizens, ‘Please vote,’” Cardenas said. “The more people who vote, the better the results are.”

Some credited Trump for their attendance.

Jennifer Bruns, 49, joined her husband and their two teenage sons at Democratic Rep. Brad Schneider’s suburban Chicago town hall, which vastly overflowed the 225-seat Northbrook Public Library. She was apolitical before Nov. 8.

Trump’s election “absolutely lit a fire under my butt, not just to take interest,” Bruns said, “but that I have a responsibility to do whatever I can to make sure our values stay in place.”

In the inevitable way of both politics and physics, the pushback to Trump and the Republican Congress drew its own pushback.

(Trump weighed in via Twitter: “The so-called angry crowds in home districts of some Republicans are actually, in numerous cases, planned out by liberal activists. Sad!”)

In Mariposa, the audience included hundreds who turned out in support of the president and McClintock, who left his last town hall, held outside Sacramento earlier this month, under police escort.

Owen Swart, 58, came wearing a National Rifle Assn. ball cap and “Infidel” T-shirt, declaring his love of both pork and guns. “If that offends you,” his shirt read, “I’ll help you pack.”

It was important, he said, to show that liberal march-ers who flooded the streets after Trump’s inauguration and those questioning the president’s legitimacy — and sanity — don’t speak for him or those he knows.

“We may not make as much noise and have signs,” said Swart, a financial advisor in Modesto, “but we work hard and we vote.”

The big question is whether the outpouring at town halls, the circuit-jamming phone calls to Capitol Hill and the email- and letter-writing campaigns are the start of a meaningful political movement or merely an angry spasm. The answer is unknowable until the next nationwide election in November 2018.

McClintock offered this advice on meeting with constituents in the meantime:

“If you’re going to do it, get the biggest room you can.”

Barabak reported from Mariposa and Cherwa from Clermont, Fla. Times staff writer Kurtis Lee in Los Angeles and special correspondents Jenny Jarvie in Savannah, Ga., and Lee V. Gaines in Northbrook, Ill., contributed to this report.

ALSO

Trump administration clears the way for far more deportations

Here’s how Trump’s new national security advisor differs from the ousted Flynn

Love or hate President Trump? It may all be in your head

UPDATES:

7:15 p.m.: Updated with changes to highlight Rep. Tom McClintock’s town hall in Mariposa.

This article was originally published at 2:10 p.m.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.