Q&A: Here’s what you need to know about the Republican memo everyone is talking about

The memo reportedly alleges that the FBI abused its surveillance authority in connection with a secret court warrant.

For weeks, it has sometimes seemed that the only thing people in Washington were talking about was a classified memo that almost no one was actually allowed to read.

Now that it’s public, it’s time to break down what this controversial document is all about.

Where did the memo come from?

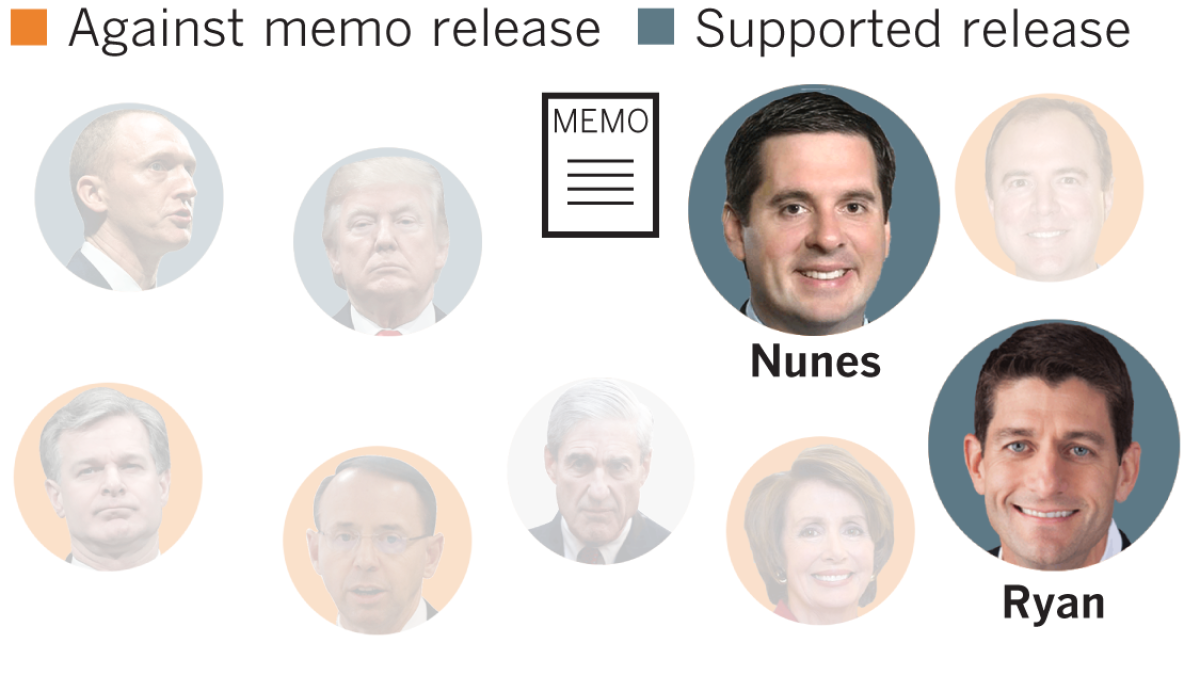

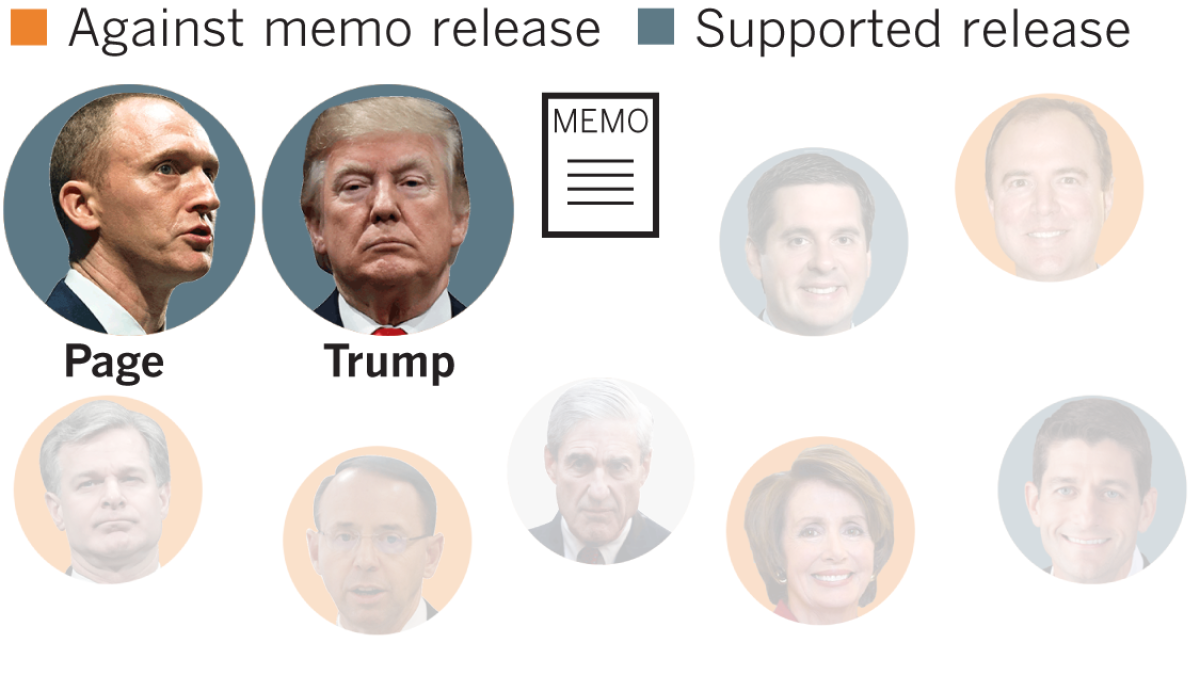

The memo was written by staff working for Rep. Devin Nunes (R-Tulare), who chairs the House Intelligence Committee and is one of President Trump’s closest allies in Congress. With the support of House Speaker Paul D. Ryan (R-Wis.), Nunes spent months demanding sensitive records from the FBI and the Justice Department, including the highly classified evidence used to support a warrant application to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court. The Nunes team then wrote a four-page memo summarizing what they thought were the most important problems with the process. Democrats on the committee did not have any input into the report, nor did many of Nunes’ Republican colleagues.

What does this have to do with the Russia investigation?

Not much. The memo focuses on government surveillance, approved by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, of Carter Page, who served as a foreign policy advisor to the Trump campaign. The first application for a warrant came in October 2016, after Page had left the campaign amid questions about his contacts with Russian officials. Page has not been charged with a crime, and has accused the government of improperly eavesdropping on him.

But the memo confirms that another Trump aide, George Papadopoulos, “triggered the opening” of the investigation that is now headed by special counsel Robert S. Mueller III into whether Trump or his aides assisted Russian meddling in the election. Papadopoulos reportedly confided to an Australian diplomat in July 2016 that Russian intelligence officials had obtained Democratic Party emails, and the diplomat passed the warning to the FBI. Papadopoulos pleaded guilty last October to lying to the FBI about his contacts with Russian officials and is cooperating with Mueller’s team.

April 6, 2017

Nunes steps aside from leading his committee's Russia investigation amid an ethics controversy over whether he inappropriately disclosed classified information.

August 24, 2017

Despite stepping back from the Russia case, Nunes is probing how law enforcement have handled their investigation. He subpoenas records from the Justice Department.

December 7, 2017

Nunes is cleared by the House Ethics Committee.

January 3, 2018

Chris Wray and Rod Rosenstein appeal to Paul Ryan to avoid turning over some sensitive records to Nunes, but Ryan backs up Nunes.

January 18, 2018

House Intelligence Committee votes to make the memo privately available to every member of the House.

January 29, 2018

House Intelligence Committee votes to release the memo, sending it to the White House for review.

January 30, 2018

Trump is caught on a hot mic saying he "100%" wants to release the memo even though administration officials said he hadn't read it yet.

January 31, 2018

The FBI publicly says it has "grave concerns" with the accuracy of the memo.

February 1, 2018

A senior administration official says Trump will give the green light for the House to release the memo.

The memo was classified as top secret. How is it becoming public?

The House Intelligence Committee is using a process that experts say has never been used before. After allowing all members of the House the opportunity to read the secret document — about 200 reportedly did — the committee voted along party lines to send it to the White House. Trump had five days to object to its release, but he declassified it on Friday. The committee also voted on party lines to block the simultaneous release of a Democratic rebuttal, saying it needs to go through the same process.

Why have Republicans and conservative commentators been saying this is so scandalous?

Before the memo became public, there was a steady drumbeat of dark statements about its contents. Fox News host Sean Hannity said “this makes Watergate look like stealing a Snickers bar from your local candy store.” After releasing the memo, Nunes said his research had “discovered serious violations of the public trust.”

The basic thrust of their concerns is this: When the Justice Department asked the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, also known as the FISA court, for a surveillance warrant on Page, some of the information to back up the request came from Christopher Steele, a former British spy who was a longtime FBI source. At the time, Steele was working for Fusion GPS, a research firm that had been hired first by anti-Trump Republicans and later by Democrats to collect opposition research on Trump. The source of Steele’s funding was not disclosed to the court, according to the memo.

Is that a big deal?

It’s hard to tell how important Steele’s research was to obtain the warrant, or if the secret court would have rejected the application had they known more about him. Instead, they reauthorized it three separate times, each time by a different judge. Classified applications to the surveillance court normally are 50 or 60 pages, while the Republican memo is only four. "You need to know the totality of what's in the affidavit to know if it's relevant,” said Orin Kerr, a USC law professor and an expert in criminal procedure.

There’s also a question about whether the identify of Fusion GPS’ client is relevant. It’s not unusual for law enforcement to field tips from politically motivated sources. "The FBI gets information from mobsters and terrorists on a regular basis,” said Benjamin Wittes, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “It seems a little peculiar to suggest they can’t get it from Democrats.”

So how important was the dossier to obtain surveillance?

Like so many other things about the memo, this is hotly contested. The document references — but does not directly quote — closed-door testimony from Andrew McCabe, who recently stepped down as the FBI’s deputy director. "No surveillance warrant would have been sought from the [FISA court] without the Steele dossier information,” the memo says. Republicans have pointed to this line as proof that Democratic-funded research was a key part of the case.

McCabe’s full testimony remains classified, so it’s impossible to independently judge the memo’s accuracy. Rep. Adam B. Schiff (D-Burbank), the ranking member on the House Intelligence Committee, said the memo takes McCabe’s comments out of context. It’s also possible that the dossier piqued the FBI’s interest in Page but wasn’t crucial to establishing probable cause to conduct surveillance.

What are Democrats saying about this whole episode?

Democrats have described the memo as misleading and inaccurate, a smokescreen to give Trump political talking points to undermine the criminal investigation. House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) said Nunes should be stripped of his committee chairmanship. Schiff said Republicans were trying to “circle the wagons around the White House and distract from the Russia probe.” Republicans not only blocked simultaneous release of the Democratic response, they refused to let FBI Director Christopher A. Wray brief the panel on his concerns.

Are law enforcement and intelligence officials OK with this memo?

They are not. Top officials appointed by Trump opposed its release and some did so publicly. The FBI — which is led by Wray, who was picked by the president after he fired Comey last year — issued a statement saying it has “grave concerns about material omissions of fact that fundamentally impact the memo's accuracy.

Deputy Atty. Gen. Rod Rosenstein, who appointed Mueller and supervises the special counsel investigation, pushed back against the memo. Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats also privately expressed reservations about releasing the document.

Democrats and independent observers are concerned that the memo’s release will fray the crucial relationship between the intelligence community, which conducts much of its work in secret, and congressional committees, who are charged with providing oversight. Will agencies still want to provide the same amount of classified information if lawmakers will use it to develop and publish partisan reports of their own?

UPDATES:

2:35 p.m.: This story has been updated with additional details.

1 p.m.: This story has been updated with more details on the testimony from Andrew McCabe, the former FBI deputy director.

12:35 p.m.: This story has been updated with graphics and additional information from the memo.

This article was originally published at 10:40 a.m.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.