Trump’s first midterm pits a booming economy against one of history’s most unpopular presidents

The midterm election now just over eight weeks away is shaping up as a seismic collision between two powerful and competing forces, a rip-roaring national economy and a deeply polarizing and unpopular president.

At stake on Nov. 6 is not just control of Congress but the fate of President Trump as he faces a special counsel investigation and a series of scandals that Democrats, given the power on Capitol Hill, would eagerly exploit.

Polling and turnout in a raft of primaries and other elections suggest Democrats are highly motivated — more so than Republicans — and the party seems poised to gain strength in Washington as well as capitals across the country.

GOP hopes of forestalling a November debacle rest mainly on the strength of these boom times.

Economic growth has hit the fastest clip in nearly four years. Consumer spending is brisk. Unemployment is near an 18-year low, and average hourly wages are climbing — 2.7% in July, compared with a year ago.

“History tells you there should be a big blue wave,” said Scott Reed, a political strategist at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, but he sees prosperity acting as a breakwater. “People feel good.”

The chamber and other GOP allies are spending millions of dollars in hopes of translating those upbeat sentiments into Republican votes, airing advertisements like one praising Rep. Steve Knight — who faces a tough reelection fight against Democrat Katie Hill in the high desert outside Los Angeles — for supporting the tax bill Trump signed into law.

“It’s not cheap to live here,” says a narrator, as a scene of the L.A. skyline yields to a bird’s-eye view of the U.S. Capitol. “So when Congress cut taxes for working families, that made a difference.”

If a wave is coming, California will probably feel it for the first time in decades. Indeed, the state that beats at the heart of the Trump resistance is central to Democratic hopes of seizing control of the House.

There are six Republican-held districts in addition to Knight’s — threading through Southern California and the Central Valley — that Democrat Hillary Clinton carried. Half a dozen appear to be in play, owing not just to anti-Trump attitudes but political lines drawn to enhance competition. (Voters saw to that in 2010 by creating an independent redistricting commission.)

Still others in the Central Valley, east San Diego County and the Sierra Nevada could flip in the event of a strong Democratic tide.

Winning just a few of those contests would go a considerable way toward giving the party the 23 seats needed for a House takeover; Republicans are counting on a ballot measure repealing a state gas tax hike to boost GOP turnout and cut its California losses.

The Senate presents a different picture. Democrats face a much steeper path to take control, even though the party needs just a two-seat gain.

Democrats must defend 25 seats, compared with nine for Republicans, and several of those are in states — Indiana, Missouri, North Dakota and West Virginia included — that Trump carried by double-digits. Only two Republican-held seats, in Arizona and Nevada, appear to be as competitive.

The dynamic reflects a duality of the November election, which is essentially playing out on separate campaign battlefields.

Much of the Senate fight is being waged across rural America, a bastion of the older, mostly white, conservative-leaning voters who constitute Trump’s political foundation. (The result in California, where Dianne Feinstein faces fellow Democrat Kevin de León in her bid for a fifth full term, will not affect the balance of power.)

Will California flip the House? The key races to watch »

The contest for control of the House is being fought hardest in the ethnically and socially diverse suburbs of Orange and San Diego counties, as well as suburban Houston and Dallas, Denver and Washington, D.C., and other more moderate enclaves where the large ranks of college-educated women have stood at the fore of the anti-Trump opposition.

The result could be a loss of GOP House seats — but continued control — and a gain of seats in the Senate, which would be relief for Republicans given the headwinds the party faces. “It would be nothing short of historic,” said Rick Gorka, a national GOP spokesman.

If we wake up on the morning of Nov. 7 picking up Senate seats and maintaining control of the House, it would be nothing short of historic.

— Rick Gorka, a national Republican Party spokesman, on the party’s hopes for this tough midterm election

There are also 36 gubernatorial races across the country, including major states such as Florida, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Ohio and California, where Democratic Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom is a heavy favorite over Republican businessman John Cox in the race to succeed retiring Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown.

The results will reverberate well beyond state capitals, shaping the fight for control of Congress deep into the next decade, as the governor in many states will have final say over the political lines drawn after the 2020 census.

No two elections are alike, but history this November runs strongly in Democrats’ favor.

“Midterm elections are often an opportunity for voters who are unhappy, dissatisfied, disappointed with the president to send that signal,” said Stuart Rothenberg, who has spent decades in Washington as a nonpartisan election handicapper.

The worse a president’s standing, the harsher the referendum.

Since 1946, the party holding the White House has lost an average of more than 40 seats when a president’s approval rating sinks below 50% in polls. That’s a flashing danger sign for Republicans: Trump’s approval has hovered in the low 40% range throughout the year, a level of disapproval rivaled only by President Nixon during the Watergate scandal and President George W. Bush during the unpopular Iraq war.

Equally worrisome for the GOP are numerous signs that Democrats are more enthusiastic about voting than Republicans, a good indicator of who is more likely to turn out.

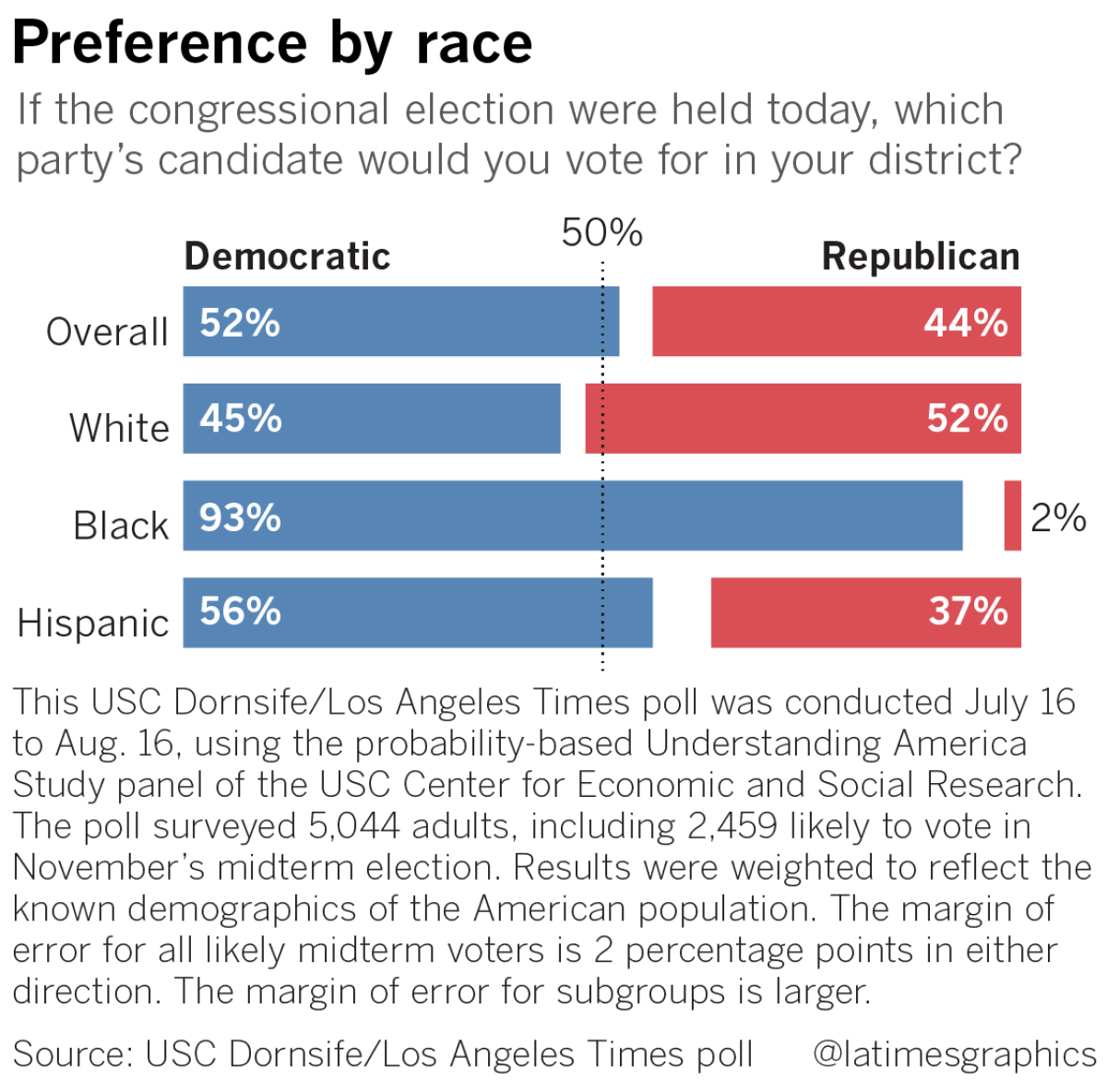

In a separate measure, the Democratic Party holds an 8-point lead in the so-called “generic ballot” — a gauge of which party voters would prefer to see controlling Congress — according to a USC Dornsife/Los Angeles Times Poll taken this summer.

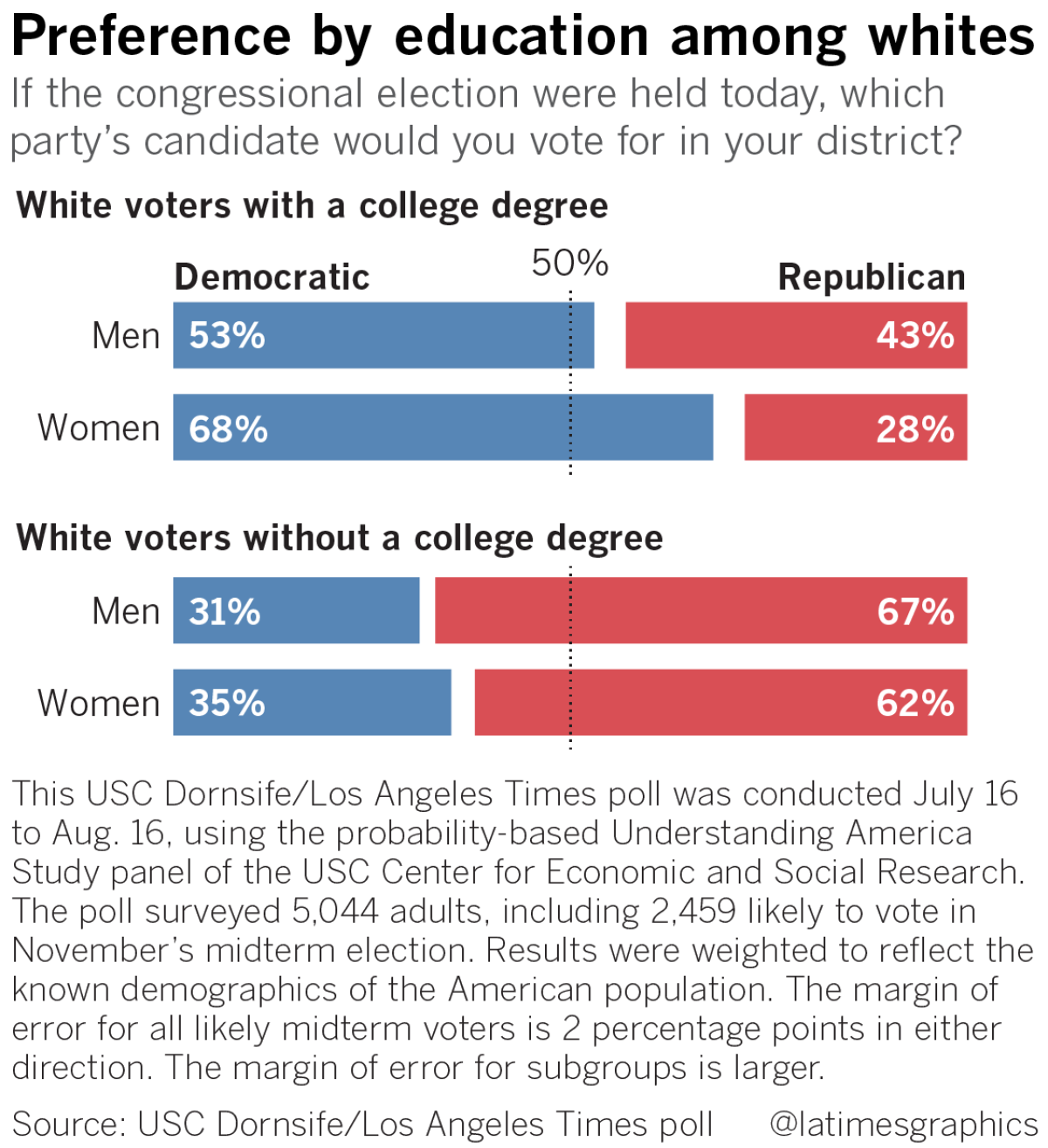

Democrats have established a huge lead among white, college-educated women, 68% to 28%, the survey suggests, and also lead among college-educated white men, 53% to 43%. They hold a significant advantage among Latinos, 56% to 37%, and an overwhelming 93%-2% edge among black voters.

Republicans have maintained a strong hold on whites without a college degree — the biggest chunk of the electorate in much of the country — and also enjoy a strong lead among residents of rural areas, matching the Democratic advantage in cities.

The challenge for Republicans trying to keep the economy front and center is a mercurial president who, at the speed of a tweet, can change the national conversation to kneeling NFL players, Bob Woodward’s new book or the “witch hunt,” as Trump calls special counsel Robert S. Mueller III’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 campaign.

“Every day the candidates are not talking about the economy and the tremendous growth is a day wasted and a step backward,” said Reed, the Chamber of Commerce strategist, who helped run the Republican Party in 1994 when a GOP tsunami swept Democrats away coast to coast. (That was the last time California, then a competitive two-party state, was caught in a midterm tide.)

“Tariffs, Mueller, shutting down the government on Oct. 1. Those are all things the White House is talking about, and all of those could have a big impact on turnout,” Reed went on. “A dose of discipline would be helpful in these next 60 days.”

For his part, Trump is described by White House aides as itching to campaign this fall, focusing mainly on protecting the Republicans’ Senate majority by appearing in friendly states the president carried, including Texas, Mississippi, Tennessee and North Dakota.

More than anything, that circumscribed itinerary suggests the challenge facing the president and his Republican Party as they try to buck history and a galvanized Democratic opposition.

In the event a blue wave comes, it will, like one of Trump’s grand properties, have his name written all over it.

Times staff writers David Lauter and Eli Stokols in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.