What you need to know before the midterm election

The midterm is fast approaching. How many races are actually competitive? Which polls should you trust? And why is California so important this year? Here’s what you need to know before the Nov. 6 election.

All 435 House seats are on the ballot. How many are truly competitive?

Here’s the main thing to keep in mind about the contest for control of the House this year: About 5 out of 6 seats in Congress really aren’t in doubt. They’re either heavily Democratic or heavily Republican, and they’re not likely to flip.

The battleground consists of roughly 60 to 70 districts nationwide, nearly all of which are in territory that Republicans have held for years – in some cases for decades. Democrats have to net at least 23 additional seats nationwide to get a majority. At least half a dozen seats in California are strongly competitive.

In the current environment, a takeover is certainly possible, but a lot of the races in these districts are very close. So if anyone pretends to know precisely how it’s going to come out, tune them out.

–David Lauter

What about the Senate?

Republicans currently control the Senate, 51 to 49.

Democrats need to flip at least two seats to gain a majority, which would give them the ability to block President Trump’s appointees to federal judgeships and a much stronger hand in legislation. But gaining those two seats is a tall order.

The 35 Senate races this year include a disproportionate number of Democratic incumbents trying to hang on in conservative-leaning states, many of which Trump carried by sizable margins. With 29 seats to defend, compared with just six for the GOP, Democrats will be hard-pressed to avoid losing ground, much less gain any.

The result in California, where Dianne Feinstein faces fellow Democrat Kevin de León as she seeks a fifth full term, will not affect the balance of power.

-- Mark Z. Barabak and David Lauter

Why is California so competitive this election cycle?

It starts, like everything else in politics these days, with Trump.

Midterm elections, virtually without exception, are a referendum on the president. And Trump is not popular in California. That’s a drag on Republican candidates such as Young Kim in central Orange County who, in another year, would probably be a shoo-in.

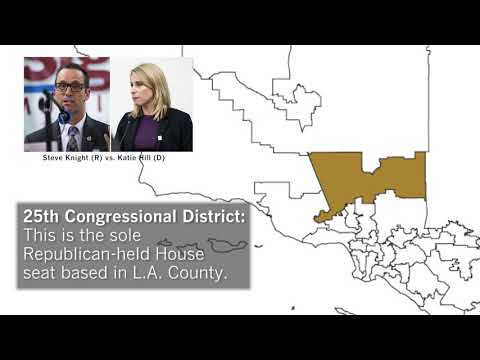

Trump is also an anchor on Rep. Steve Knight, in the high desert outside Los Angeles. In fact, all voters there seem to care about is Trump, and whether Knight and his Democratic rival, Katie Hill, are perceived as for or against him.

Then there’s Rep. Dana Rohrabacher, on the Orange County coast, who’s highly endangered because of his kind words and cozy relationship with Russia, which interfered in the 2016 election to Trump’s benefit.

But there are other, broader reasons congressional seats in traditionally Republican areas such as Orange County and north San Diego County are now competitive. The state’s growing Latino population has become more politically active and pro-Democratic in response to the belligerent tone sounded by many Republicans on the issue of illegal immigration. The GOP’s embrace of religious conservatism also pushed many live-and-let-live Californians away from the party.

But none of that would matter as much if California voters hadn’t taken matters into their own hands. Fed up with years of noncompetitive elections, voters took the political line-drawing away from self-interested lawmakers and gave it to a nonpartisan, independent commission. That’s made a big difference as well.

– Mark Z. Barabak

Is it typical for California to play such an important role in a national election?

No, not at all. It’s been three decades since the state was a presidential battleground — back in 1988 when Republican George H.W. Bush faced Democrat Michael S. Dukakis (and Bush won). It’s been longer still since the state played a meaningful role choosing a major-party presidential nominee. Successive congressional wave elections have come and passed without a ripple. But this year, with those six seats up for grabs, and maybe more, if Nov. 6 produces a blue tsunami, California is in the thick of the fight for control of the House.

– Mark Z. Barabak

What do the political oddsmakers say about California’s contests?

The nonpartisan Cook Political Report, which has tracked House and Senate races nationwide for decades, rates five of California’s 53 House contests as tossups, one as leaning Democratic and one as leaning Republican. All seven of those fiercely competitive races are for House seats held by the GOP.

Three others appear safely in Republican hands, but that could change if a Democratic wave were to become something more akin to a tidal wave.

-- Christine Mai-Duc

Democrats need 23 more seats to take control of the House. Seven of the most competitive races are in California.

How is Trump affecting candidates?

Polls show large numbers of people indicating that they feel a need to vote in the midterm to show either support for or opposition to the president.

In a place like California, Republican candidates are having to walk a fine line between motivating their base (some of whom are enthusiastic Trump supporters) and not turning off independents, who are largely ambivalent about Trump.

Orange County’s 39th Congressional District is a good example of this, where Kim, a Korean immigrant, has touted opposition to California’s “sanctuary state” policy while preaching “compassion” in immigration policy going forward.

– Christine Mai-Duc

Which voters could make the difference in California?

In largely suburban districts, like several of the ones in Southern California, women, minorities and young people are three key groups Democrats say could help them win back control of the House.

In the Central Valley, for example, major efforts are underway to reverse historically low Latino turnout in midterms. In the 25th Congressional District, the Brett M. Kavanaugh Supreme Court confirmation hearings may boost Democrats by spurring a backlash from suburban women.

Billionaire Tom Steyer’s group, NextGen America, is spending $33 million trying to get young people to vote on Nov. 6.

– Christine Mai-Duc

With so many polls, how can you tell if one is credible and accurate?

Good polls are pretty darn accurate. And since all of us live in our own bubbles — in most cases interacting mostly with people who are similar to us — polls are the best way we have to get beyond our own circles and gain a sense of what the larger public thinks.

In the 2016 presidential election, despite all the criticism afterward, polls had correctly forecast almost all 50 states.

So how come people so often say the “polls got it wrong”? In 2016, a lot of folks who like to make predictions looked at the polls that showed Hillary Clinton leading and made two big mistakes. First, they forgot that polls involve probabilities, not certainties, and, second, they forgot that national polls don’t tell you how individual states will fall.

What do we mean? Suppose we tell you that in a particular race, the odds are 90 to 10 that your party’s candidate will win. You might think that’s pretty much a sure thing. But another way of saying the same thing is that 1 out of 10 times in this situation, the underdog will win. With hundreds of contests each election year, 90-to-10 odds are very likely to lead to some upsets. That’s what happened in states like Michigan in 2016 — Trump won an upset. And he got just enough upset victories by narrow margins to win the election.

– David Lauter

How can you tell good poll data from bad poll data?

A good poll will disclose all the questions that were asked. That way you can tell if some were worded in a way that’s designed to skew the results. It will also disclose who conducted the poll, how it was conducted, when it was taken, how big the sample was and what the margin of error was. In states such as California that have large numbers of people who don’t speak fluent English, a good poll will be conducted in more than one language. A poll of Californians who are fluent enough to answer questions in English is not at all the same as a poll of all California voters.

Don’t rely too much on polls released by partisan organizations or campaigns. They typically will take several polls and only publicly release those that support their position.

Finally, don’t just rely on a single poll. No poll is correct all the time. So if you’re paying attention to a specific race, check out the average of several polls. You’ll be much less likely to be fooled.

– David Lauter

How do certain age groups tend to vote or lean when it comes to parties and issues. How do they differ when it comes to voter turnout?

Generally, younger voters lean much further left than their older counterparts, and the Silent Generation (born 1928-1945) is the most Republican.

But in midterm elections like this year, young voters consistently do not turn out at the same rates as older voters.

In researching a story about efforts to get more young voters to turn out this year, I found out that 18-to-34-year-olds have voted at lower rates than any other age group in every midterm going back to 1978. That’s 40 years of depressed turnout for young people.

–Christine Mai-Duc

In general, voter turnout goes up pretty steeply with age. In other words, older folks vote more consistently than younger ones. That’s especially true in midterm elections like this one, as opposed to presidential elections, when more people vote overall.

As for whom different groups vote for, voters younger than 30 have leaned heavily toward Democratic candidates in recent elections. That’s especially true for women. Partly, that’s because the millennial generation is more racially and ethnically diverse than older generations, and minority group members tend to support Democrats. But even factoring that out, millennials are more liberal and more Democratic. The generation older than 65 is the most Republican.

And, no, people don’t automatically get more conservative as they get older. Some generations have (baby boomers did, on average), others haven’t.

–David Lauter

Where should you vote on election day?

You can find your local polling place online via your state’s election website.

And remember to do your homework ahead of time. As the educational nonprofit News Literacy Project reminds, double-check your facts before you vote.

Some questions were submitted during this Reddit AMA.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.