Analysis: Takeaways from prosecutors’ case against Paul Manafort

Reporting from Washington — After roughly two dozen witnesses and nine days of testimony, federal prosecutors are expected to finish presenting their case against Paul Manafort on Monday. Then lawyers for President Trump’s former campaign chairman will present his defense.

The trial is the first on charges brought by special counsel Robert S. Mueller III. Manafort has pleaded not guilty to tax evasion, bank fraud and conspiracy.

Reporters and spectators have packed the stiff wooden pews every day of the trial. Here’s what we’ve learned so far.

The case really isn’t about Russia.

Prosecutors disclosed before the trial that they didn’t expect to present evidence of an election-related conspiracy with Russians, and they’ve stuck to that. There has been no talk of Russian meddling in the campaign — nothing about hacking of emails, social media misinformation or secret back channels to the Kremlin.

But there could be Russia connections at some point.

The trial has still produced some bread crumbs that could lead to Moscow, although their significance is unclear.

For example, the jury learned that Konstantin Kilimnik had access to some of Manafort’s offshore bank accounts. Kilimnik was Manafort’s business partner in Ukraine, but he’s also alleged to have ties to Russian intelligence.

There have also been references to Oleg Deripaska, a businessman close to Russian President Vladimir Putin. Deripaska paid Manafort $10 million disguised as a loan to evade U.S. income taxes, according to testimony from Manafort’s former accountant.

Follow the latest news of the Trump administration on Essential Washington »

Manafort was broke when he started working for the Trump campaign — for free.

It’s one of the enduring mysteries of Manafort. He joined the Trump campaign in March 2016 and didn’t take a salary for the five months he stayed. It was a strange decision for a businessman under tremendous financial pressure.

He was still trying to collect more than $2 million for his work in Ukraine two years earlier, and he was struggling to pay mounting bills for an exorbitant lifestyle involving lavish homes, custom clothing and expensive cars.

It’s possible that Manafort figured the Trump campaign would catapult him back into the top ranks of political operatives and Washington lobbyists after years of working overseas. In a situation like that, working for free could pay off in the end.

But there are darker insinuations as well. Did Manafort’s dire straits make him vulnerable to coercion? Was he still seeking overseas work while steering a U.S. presidential campaign? There could be more to learn here.

Manafort didn’t do anything alone.

Not everyone went along with Manafort’s alleged criminal schemes. But a constellation of people looked the other way or helped out.

Cindy Laporta, who worked as an accountant for Manafort, handled financial documents she believed to be false, submitting them to banks or the Internal Revenue Service. (She received immunity to testify.)

Then there was a lawyer in Cyprus nicknamed Dr. K, who worked with Manafort to set up offshore accounts in the Mediterranean island nation and later in the Caribbean.

And of course there was Richard Gates, Manafort’s right-hand man at his company and his deputy on the Trump campaign.

Gates apparently was indispensable. He testified that he doctored documents, arranged wire transfers and submitted false information to banks, all so Manafort could pay less in taxes or obtain fraudulent loans.

Gates is dirtier than we realized.

When Manafort was first indicted last October, Gates was charged with some of the same financial crimes. Those charges and more were dropped in February when he cut a deal to cooperate with prosecutors.

On the witness stand, Gates admitted to those crimes and much more, giving defense attorneys plenty of ammunition to question his credibility and his character. Not only has he already pleaded guilty to lying to federal prosecutors, he admitted to inflating his income in applications for mortgages and credit cards and embezzling hundreds of thousands of dollars from Manafort’s company.

His personal life appeared a mess as well. He had an apartment in London where he conducted an extramarital affair, and he admitted to spending far more money than he could afford.

Defense attorney Kevin Downing took every opportunity to highlight what he calls Gates’ “secret life.” On Wednesday, he suggested that Gates may have had not just one, but four sexual affairs — but the matter was dropped after prosecutors objected.

There are connections to the 2016 campaign and the Trump inauguration.

The charges against Manafort are mostly unrelated to his work for Trump, but not entirely. He helped Stephen Calk, chief executive of the Federal Savings Bank of Chicago, secure a position as an economic advisor on the campaign after Calk approved one of Manafort’s bank loans.

After Trump won, Gates was still working for Trump, and Manafort tried to leverage the connection to get Calk an administration job. “We need to discuss Steve Calk for Sec of the Army,” Manafort wrote Gates in a November 2016 email. “I hear the list is being considered this weekend.”

There’s more overlap with Trump’s inaugural committee, which Gates served on as a deputy chairman. During cross-examination of Gates, Downing asked whether he used any of the committee’s funds for personal expenses. Gates didn’t deny it. “I don’t recall,” he said. “It’s possible.”

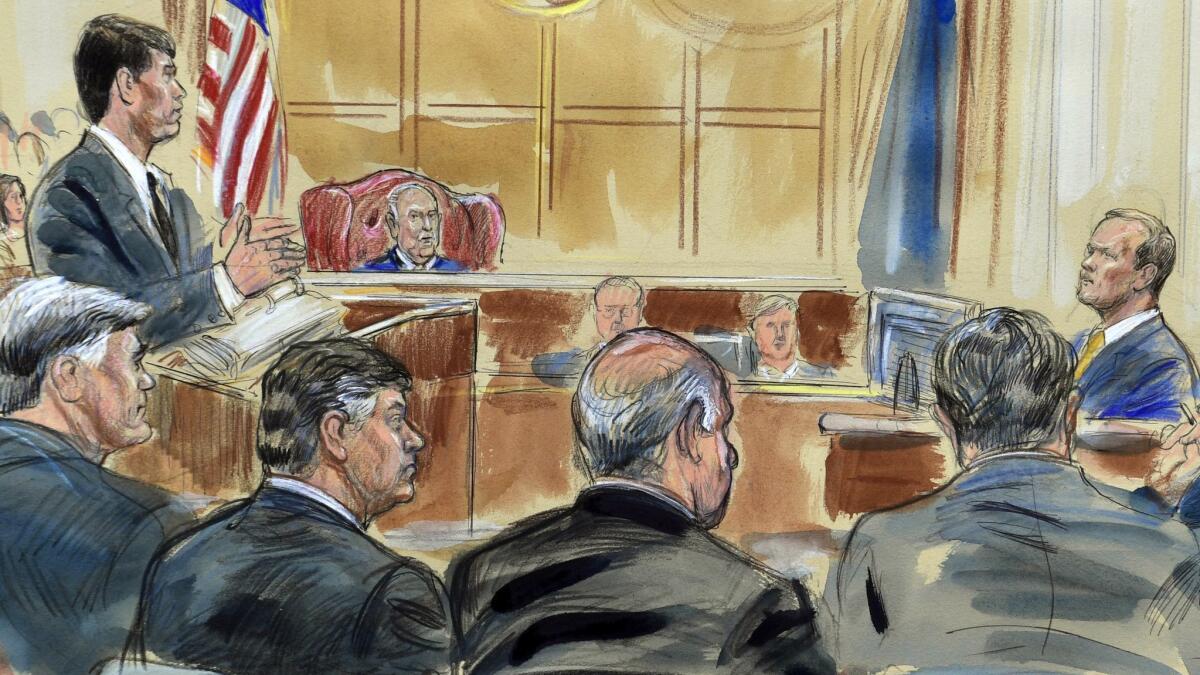

The judge is a wild card.

Judge T.S. Ellis III has been a constant source of drama during the trial, drawing laughter with his bon mots and quieting the courtroom with his outbursts.

He has frequently pushed prosecutors to present their case more quickly, and they’ve striven to pare down their questioning of witnesses when possible.

But the prosecution has still taken heat in the courtroom. On Wednesday, fuming at the bench, Ellis berated Assistant U.S. Atty. Uzo Asonye for allowing an IRS agent testifying as an expert witness to sit in on the court proceedings.

After the special counsel’s office objected to the judge’s outburst in front of the jury, Ellis retreated on Thursday, telling the jurors to “put that aside” and admitting he might have been wrong. “This robe doesn’t make me anything other than human, and I may have made a mistake,” he said.

Twitter: @chrismegerian

UPDATES:

2:56 p.m.: This story was updated after court adjourned Friday.

This story was published at 3 a.m.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.