After Ford testifies she was sexually assaulted, Kavanaugh responds with anger and tears

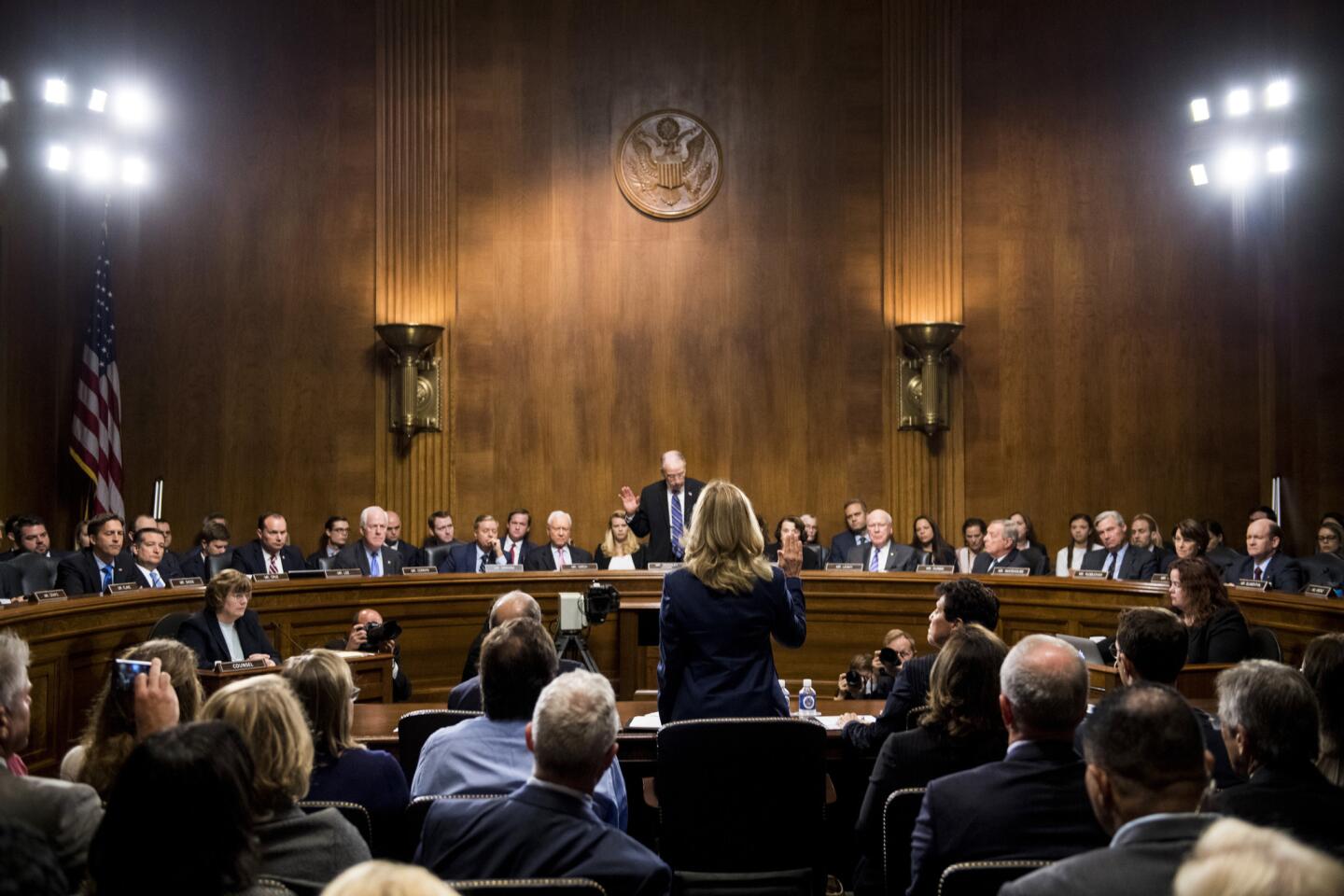

Christine Blasey Ford, who has accused Supreme Court nominee Brett M. Kavanaugh of sexually assaulting her in high school, testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Thursday.

Reporting from Washington — Judge Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination hung in the balance Thursday night as Republicans calculated whether they had the votes to confirm him following a highly anticipated showdown filled with hours of raw, emotional testimony.

After meeting Thursday night, Republican senators expressed confidence that Kavanaugh would be approved by the Senate Judiciary Committee in a vote Friday morning, but acknowledged the outcome would be close. Preliminary votes by the full Senate are scheduled to begin Saturday, with a final vote next week.

But key members from both parties, whose decisions will likely determine Kavanaugh’s fate, have yet to signal how they will vote, a worrisome sign for Senate Republicans, who, clinging to a narrow majority, hoped to swiftly confirm a staunchly conservative jurist for a lifetime seat on the high court.

The dramatic testimony Thursday by Christine Blasey Ford, the California professor who has accused Kavanaugh of sexually assaulting her when they were high school students, threatened to derail the nomination.

Ford told the Senate Judiciary Committee that a drunken Kavanaugh and his friend Mark Judge locked her in a bedroom during a 1982 gathering and that Kavanaugh tried to rape her.

When asked about her most indelible memory, Ford recalled the “uproarious laughter between the two, and their having fun at my expense.” She told the senators she was “100%” certain Kavanaugh was her attacker.

Both Kavanaugh and Judge have denied the allegations.

When it was his turn to testify, Kavanaugh responded with anger and emotion, almost shouting his opening statement and stopping repeatedly to fight back tears and compose himself. Kavanaugh said he had no ill will toward Ford, but denied her allegations.

Echoing now-Justice Clarence Thomas’ condemnation of the “high-tech lynching” he said he had endured during his 1991 confirmation hearing, Kavanaugh called what has happened to him a “national disgrace.”

It was a surprisingly raw display of rage and passion for a judicial nominee, but his supporters said it reflected the heartfelt frustration of a man who thinks he’s been wrongly accused.

“He’s righteously incensed, and I don’t blame him,” said Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah.).

Kavanaugh’s sharply partisan complaints were highly unusual for a Supreme Court candidate. He accused Democrats of “lying in wait” to attack him, frequently interrupted and mocked Democratic senators during questioning and attributed his treatment to “revenge on the behalf of the Clintons.” Kavanaugh is a longtime GOP attorney who worked with special counsel Kenneth Starr to investigate former President Bill Clinton.

Noting the Senate’s role in the process of confirming Supreme Court nominees, he said Democrats “have replaced ‘advise and consent’ with ‘search and destroy.’”

Marc Short, the Trump administration’s former liaison to Congress, predicted that Kavanaugh’s impassioned testimony would help him win confirmation along party lines.

Trump was glued to the television and heartened by the fiery testimony, aides said. One senior administration official involved in the confirmation process described Kavanaugh’s performance as “powerful...strong...game changing” in a text message.

The president was “happier” to see Kavanaugh defending himself so strongly, another administration official said, as Trump had counseled Kavanaugh to do earlier in the week after the nominee and his wife appeared on Fox News.

Immediately after the hearing, Trump tweeted, “Judge Kavanaugh showed America exactly why I nominated him. His testimony was powerful, honest, and riveting. Democrats’ search and destroy strategy is disgraceful and this process has been a total sham and effort to delay, obstruct, and resist. The Senate must vote!”

Democrats repeatedly pressed Kavanaugh on his reputation for drinking and partying while in high school and college, and tried, without success, to get him to call for an FBI investigation into Ford’s allegations. The White House and GOP leaders have said there is no need for the FBI to get involved.

Democrats praised Ford for sharing her story.

“You have given America an amazing teaching moment,” Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) told Ford, causing her to choke back tears.

Ford’s combination of emotional fragility — evident in her face and voice — and her precise recall of certain facts and details made the California professor a powerful witness. She had not been seen or heard in public since her story gained the national spotlight two weeks ago.

Ford also described the harassment, death threats and other blowback she has endured since coming forward. “I am here not because I want to be,’’ she told the Senate Judiciary Committee. “I’m terrified.”

She emphasized that she had originally reported the alleged incident to Democratic lawmakers before Kavanaugh was selected by President Trump and denied having any political motivations.

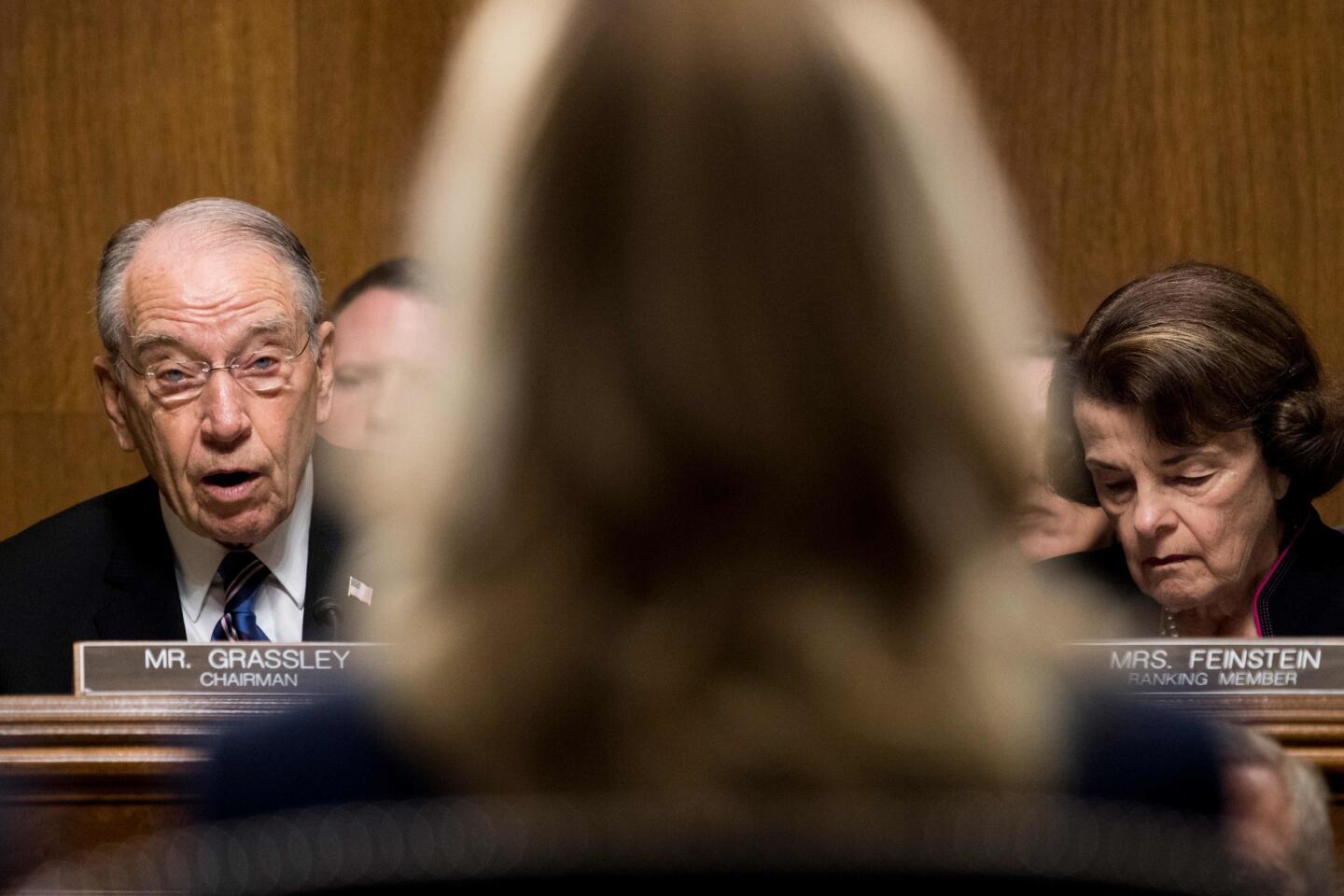

As Ford testified, her training as a research psychologist periodically became obvious. Asked by Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) about the impact that the alleged attack had on her life, Ford referred to the “sequelae” of the attack, a psychology term that refers to the symptoms that can follow a traumatic event. Ford has a doctorate in educational psychology from USC.

The sequelae of sexual assault vary from victim to victim, she noted, adding that in her case, she had suffered from “PTSD-like” symptoms, including claustrophobia.

Later, Feinstein asked how she could be sure that it was Kavanaugh who had put his hand over her mouth to prevent her from screaming.

“The same way that I’m sure that I’m talking to you right now,” she responded. “Basic memory function.”

Ford went on to refer to the way neurotransmitters in the brain record memories in the hippocampus, a portion of the brain that plays a central role in human memory.

But her responses were not entirely clinical. Asked by Feinstein if there was a possibility that this could be a case of “mistaken identity,” Ford’s response was simple.

“Absolutely not.”

At times Ford’s California informality, nervousness and lack of experience in public speaking contrasted sharply with the usual stiffness of Senate proceedings in Washington. She joked about needing caffeine, referred to childhood “beach friends,” spoke of her fear of flying and often took deep breaths. At one point she drew sympathetic laughter when she asked for the definition of “exculpatory evidence.”

She said events regarding her coming forward publicly unfolded so quickly this summer that she was interviewing potential attorneys from her car in a Walgreens parking lot while on vacation.

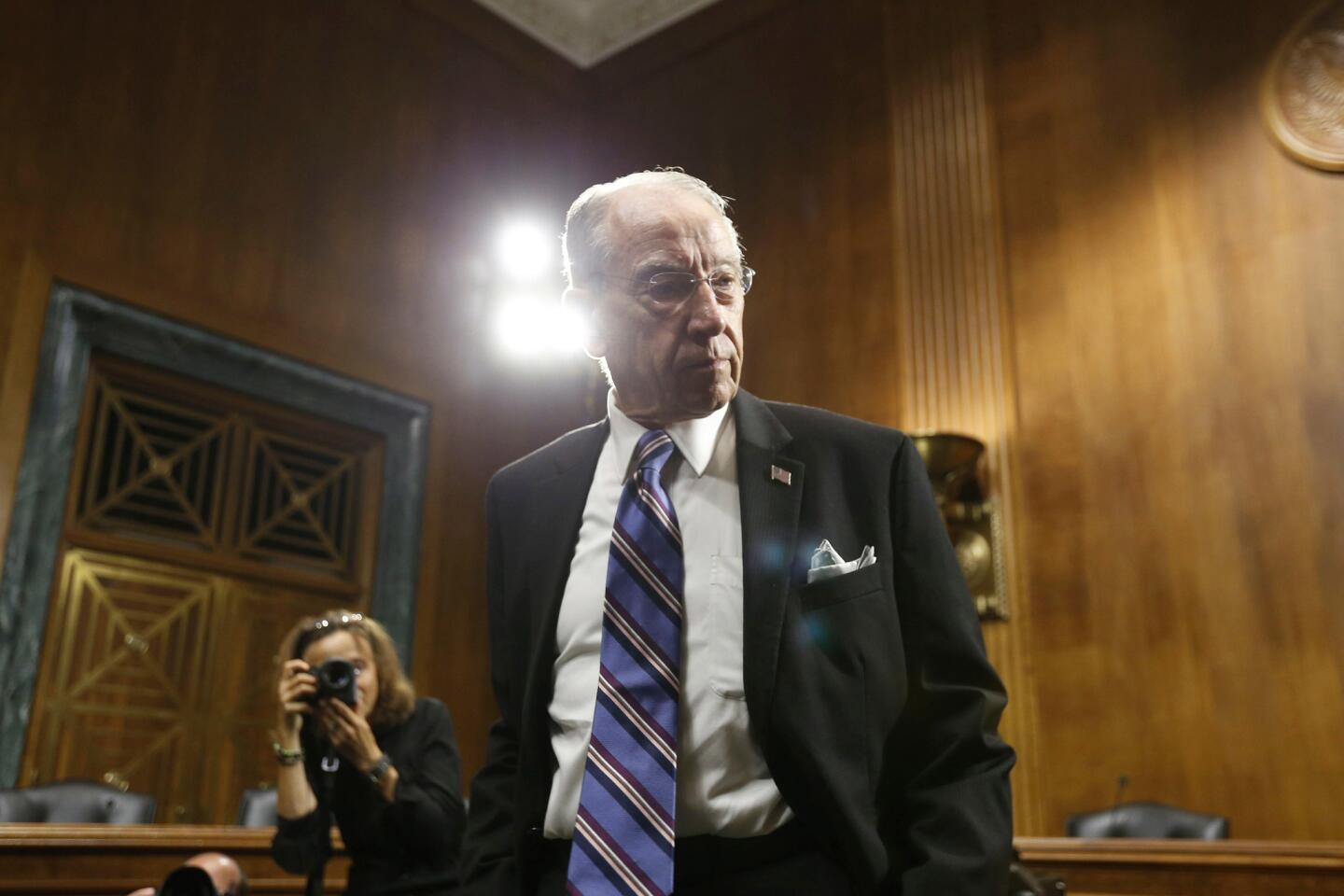

Sen. Charles E. Grassley (R-Iowa), chairman of the committee, opened the hearing by apologizing to both Kavanaugh and Ford for the intense media scrutiny and threats they’ve had to endure. He also called on fellow members to maintain civility, but then launched into a partisan attack on how Democrats handled the allegations, which became public days before the committee planned to vote on Kavanaugh.

Feinstein, the ranking Democrat on the committee, defended her actions, saying she kept the allegations confidential at the request of Ford. In her opening statement, Ford thanked Feinstein for her discretion. “Sexual assault victims should be able to decide for themselves whether their private experience is made public.”

Some of the most impassioned comments came from the senators themselves, particularly Republicans, who compared Democrats’ efforts to question Kavanaugh about Ford’s allegations to the anti-communist McCarthy hearings in the 1950s.

“This is the most unethical sham since I’ve been in politics,” said Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.).

The committee has 11 Republicans and 10 Democrats, and the Republican majority — all of whom are men — recruited Rachel Mitchell, a sex crimes prosecutor from Arizona, to conduct the questioning for them. GOP leaders were anxious to avoid the optics of older, all-male senators grilling Ford, as occurred during the Clarence Thomas-Anita Hill hearing in 1991.

Mitchell’s questioning of Ford was limited to five-minute segments, since she was effectively filling the time afforded to Republican members of the committee. As a result, she frequently had to interrupt her examination, sometimes in the middle of question, to allow a Democratic lawmaker a turn to ask questions for five minutes.

Mitchell focused largely on exploring how Ford decided to go public with her story, who paid for her polygraph test, who recommended potential attorneys and other details that might bolster Republicans’ claims that Ford was being manipulated by Democrats for political purposes.

But conservative television commentators voiced frustration that Mitchell wasn’t able to undermine Ford’s story, and after Kavanaugh began to testify, Mitchell was largely shunted to the sidelines as Republican senators took over the questioning.

During a break in Ford’s testimony, some Republican lawmakers’ comments inadvertently demonstrated why GOP leaders opted to leave the questioning of Ford to Mitchell.

Asked whether he found Ford credible, Hatch said, “I think she’s an attractive, good witness.” Asked to clarify what he meant by attractive, Hatch added, “In other words, she is pleasing.”

Later, Graham said he felt “ambushed” by the way the assault allegations were raised so late in the confirmation process, a questionable word choice given Ford’s allegation of attempted rape.

But generally there were stark differences between the examinations of Ford and Hill, who endured relentless questioning from Republican senators. The late Sen. Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania accused Hill of committing “flat-out perjury” in her claim that Thomas had sexually harassed her at work.

In the past week, two other women have come forward to lodge similar allegations against Kavanaugh that involve heavy drinking and abusive behavior.

Deborah Ramirez told the New Yorker of a humiliating sexual incident when she was a freshman at Yale and joined a drinking game with several others, including Kavanaugh.

On Wednesday, Julie Swetnick filed a sworn declaration in which she recalled being at several parties where Kavanaugh and Judge were drunk and abused young women who were also drunk. Kavanaugh has denied both accusations.

Times staff writers Eli Stokols and Noah Bierman contributed to this report.

More stories from David G. Savage »

Twitter: DavidGSavage

UPDATES:

5:55 p.m.: This article was updated with details on Democrats’ questions and comments at the hearing.

5:15 p.m.: This article was updated after the GOP meeting ended.

4:45 p.m.: This article was updated with the Republican meeting.

3:30 p.m.: This article was updated with Trump’s reaction.

2:25 p.m.: This article was updated with additional comments from Kavanaugh and Graham.

1:25 p.m.: This article was updated with a comment from Hatch about Kavanaugh’s statement.

12:45 p.m.: This article was updated with Kavanaugh’s opening statement.

11:50 a.m.: This article was updated with comments from Graham and others.

10:40 a.m.: This article was updated with details from the Clarence Thomas-Anita Hill hearings.

10:15 a.m.: This article was updated with a comment from Hatch.

9:50 a.m.: This article was updated with more details from Ford.

8:45 a.m.: This article was updated with Ford’s referring to scientific terms.

8:20 a.m.: This article was updated with more details from Ford’s testimony.

7:55 a.m.: This article was updated with Ford’s opening statement.

7:20 a.m.: This article was updated with comments from Grassley and Feinstein.

This article was originally published at 7 a.m.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.