Republicans’ latest plan to repeal Obamacare’s insurance requirement could wreak havoc in some very red states

Reporting from Washington — The Senate Republican plan to use tax legislation to repeal the federal requirement that Americans have health coverage threatens to derail insurance markets in conservative, rural swaths of the country, according to a Los Angeles Times data analysis.

That could leave consumers in these regions — including most or all of Alaska, Iowa, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada and Wyoming, as well as parts of many other states — with either no options for coverage or health plans that are prohibitively expensive.

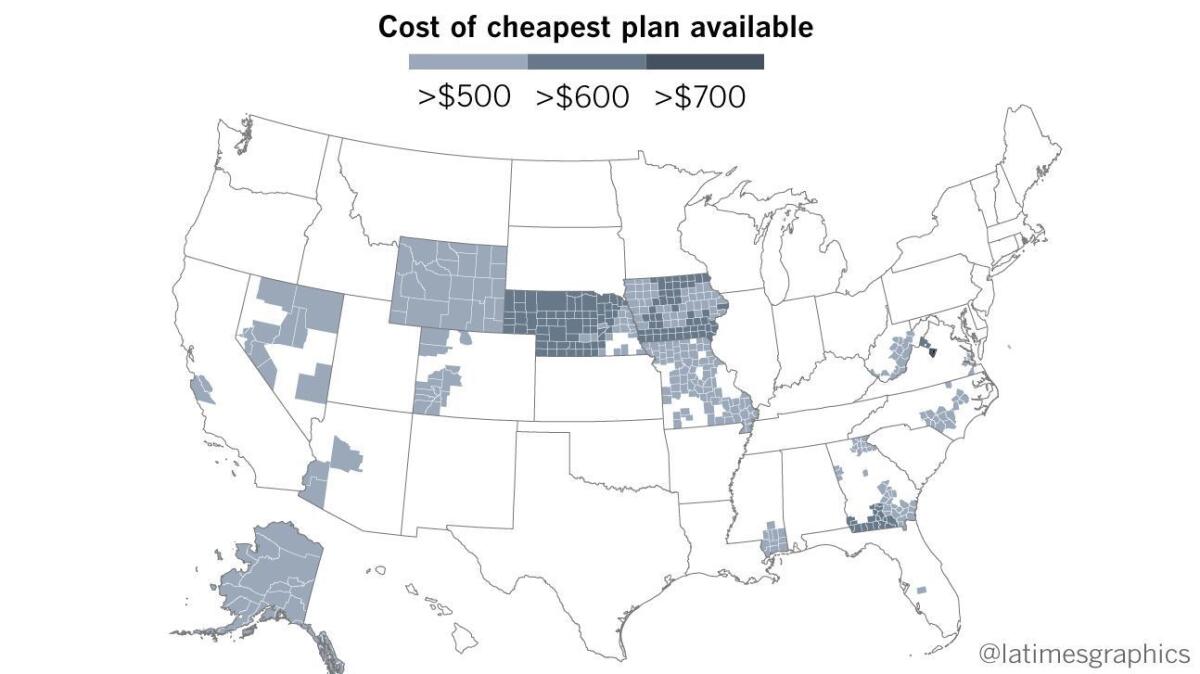

There are 454 counties nationwide with only one health insurer on the marketplace in 2018 and where the cheapest plan available to a 40-year-old consumer costs at least $500 a month. Markets in these places risk collapsing if Congress scraps the individual insurance mandate.

“It’s very, very concerning to us,” said Denise Burke, healthcare analyst at the Department of Insurance in Wyoming, where the cheapest plan for a 40-year-old consumer in most of the state will cost $586 a month next year.

The precise nationwide impact of the Senate GOP tax plan, which would eliminate the Affordable Care Act’s unpopular mandate penalty, is unclear, as many forces affect how much insurance costs and where insurers sell plans.

But the legislation is widely expected to cause insurers to raise prices or exit markets out of fear that fewer healthy people will buy plans if there is no longer a penalty for going without coverage.

The risk is greatest in places where health insurance is already very expensive and where there are few insurers.

For example, there are 454 counties where there will be only one insurer selling marketplace plans in 2018 and where the cheapest plan for 40-year-old consumer will cost more than $500 a month, according to the Times analysis, which is based on data from the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation.

“Repealing the individual mandate will affect insurance markets everywhere,” said Larry Levitt, a health insurance expert at the foundation. “But markets where there is already little choice and high premiums are especially vulnerable.… Rural areas could be especially hard hit.”

Eighty-six percent of these 454 at-risk counties have fewer than 50,000 residents, census data show. Healthcare costs are often higher in rural areas, as there are fewer medical providers and populations tend to be older and sicker.

These counties also overwhelmingly supported Donald Trump last year, with 9 out of 10 backing the Republican presidential ticket, according to election data.

In addition to Alaska, Iowa, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada and Wyoming, the counties are clustered in southwestern Arizona, western Colorado, southern Mississippi, central North Carolina, as well as parts of Georgia, Virginia and West Virginia.

There are also two counties in California — Monterey and San Benito — and two in Florida — Hardee and Monroe — with only one choice of insurer and extremely high premiums.

There are many more counties — including most in the southeastern United States — where there is only one insurer, though premiums are not quite as high.

Republican congressional leaders argue that eliminating the mandate penalty, which is technically a tax, will save many Americans money, especially coupled with other cuts promised in the GOP tax legislation.

“The individual mandate isn’t just any tax. It’s a terribly regressive tax that imposes harsh burdens on low- and middle-income taxpayers,” Senate Finance Committee Chairman Orrin G. Hatch (R-Utah) said as his panel debated the tax bill this month.

“Zeroing it out means we have a chance to provide greater tax relief to middle-class families, through both reduced penalties and lower overall rates.”

The insurance mandate — which subjects Americans who don’t have coverage to an annual penalty of $695 or 2.5% of income, whichever is larger — has always been the most unpopular part of the 2010 healthcare law, often called Obamacare.

But most experts agree that eliminating the mandate without some other mechanism to encourage young, healthy Americans to get coverage could have disastrous consequences for the individual insurance market, which serves consumers who don’t get coverage through an employer or a government plan such as Medicare or Medicaid.

Independent analyses by the American Academy of Actuaries, the Congressional Budget Office and others suggest that without some kind of penalty, many Americans would wait to get insurance until they are sick. That would push up premiums, driving away more consumers and causing what is known as a death spiral.

Several states, including Washington, experienced just this kind of market collapse when they tried guaranteeing their residents coverage without any kind of requirement that all people — including the young and healthy — get coverage.

“It’s kind of insurance 101,” said Jim Havens, who oversees individual market sales for Premera Blue Cross, a leading insurer in Washington state. Premera will be the only insurer on Alaska’s marketplace next year.

“If you only have people who need care the most, insurance becomes really expensive really fast,” Havens said. “A mandate is fundamentally so important to make insurance affordable.”

Virtually every major physician group, hospital association and patient advocate group has called on congressional Republicans not to scrap the mandate.

“Repealing the individual mandate without otherwise increasing access to adequate, affordable health insurance is a step backwards for individuals and families,” the American Heart Assn., the American Lung Assn., the March of Dimes, Consumers Union, the advocacy arm of the American Cancer Society and 11 other patient groups warned in a letter to Congress.

Access and affordability are already a challenge in many parts of the country, as insurers have struggled to adjust to new rules imposed by the health law, including requirements that health plans cover sick consumers and offer a basic set of health benefits.

And though many Americans who qualify for financial aid through the healthcare law have been cushioned from high premiums, consumers who earn too much to get insurance subsidies face eye-popping bills.

The health law provides premium assistance to people with annual incomes between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level, or between $12,060 and $48,240.

There were signs that markets were stabilizing in many parts of the country until this year’s GOP push to repeal the law, which included moves by the Trump administration to cut enrollment efforts and stop a separate monthly payment to insurers, used to lower the cost of deductibles and co-payments for low-income consumers.

Those steps prompted many insurers to leave markets or dramatically raise premiums for 2018.

“All of that is driving the markets crazy,” said Barbara Richardson, insurance commissioner in Nevada, where 11 of the state’s 17 counties are among the 454 nationally with just one insurer and extremely high premiums. “Any time you shake up the market … you are going to have a rise in prices.”

Richardson, who serves a Republican governor, said regulators are particularly concerned about those state residents who don’t qualify for government subsidies. The cheapest plan available next year to a 40-year-old consumer will cost at least $543 a month in those 11 Nevada counties.

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Wyoming, the only insurer selling plans on that state’s marketplace, raised its rates by 48% on average in 2018, in part to reflect uncertainty about events in Congress.

Wendy Curran, vice president of the Wyoming health plan, said the insurer, a locally run nonprofit, is committed to remaining in the market. “We consider ourselves part of the fabric of the state,” she said.

But Curran acknowledged that coverage is increasingly out of reach for state residents who don’t qualify for government aid.

“By anyone’s standards, these prices are very high,” she said.

ALSO

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.