Tom Steyer’s bets on private prisons and coal mining could spell trouble in 2020

When Tom Steyer was running a hedge fund in 2000, he wrote a letter telling some wealthy investors their money would soon flow through an offshore company that would shield their gains from U.S. taxes.

It was routine in finance, but could prove toxic in politics.

Now that the San Francisco billionaire has joined the crowd of Democrats running for president, much of what he did to build his personal fortune, including a stint at Goldman Sachs in the 1980s, could turn off voters. His fund’s investments in coal mining and private prisons are two of the biggest hazards.

Part of Steyer’s challenge is timing. Wall Street’s reputation is in tatters in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Many Democrats are upset about growing income inequality. And billionaires — President Trump first among them — are routinely demonized by the party’s left wing.

Steyer is the founder of Farallon Capital Management, one of America’s largest hedge funds, the high-risk investment pools for big investors. He left Farallon in 2012 after running the San Francisco firm for 26 years.

He did not mention his experience there when asked by The Times what qualified him to serve as president. He focused instead on his work fighting climate change and big corporations over the last decade.

Attacks by Steyer’s opponents have been mild so far, but that will change if he starts gaining support.

“He will have to answer for his involvement in anti-climate-control activities, his relationship to the coal industry, and his relationship to Wall Street, which young people particularly find abhorrent,” said Democratic ad maker Hank Sheinkopf, who is unaligned in the presidential race.

“In a political campaign, there is no past tense and there is no future tense. Everything in your life you’ve ever done, thought of and said is in present tense.”

In written responses to questions sent by email, Steyer expressed remorse over some of Farallon’s investments.

A key liability is Farallon’s 2005 investment of $34 million in Corrections Corp. of America, which runs migrant detention centers on the U.S.-Mexico border for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Many of the roughly two dozen Democrats in the presidential race have denounced profits from incarceration as immoral.

“I deeply regret that Farallon made that investment, and I personally ordered the investment in CCA to be sold because it did not accord with my values then or now,” Steyer said.

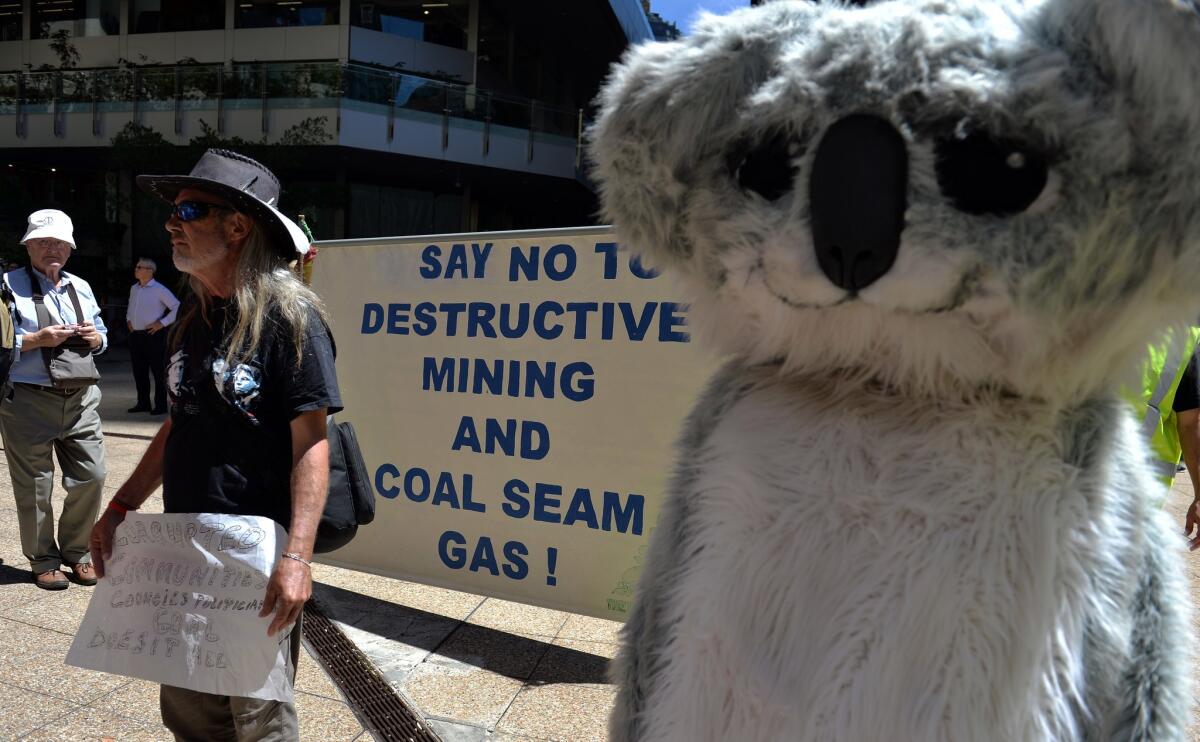

More troublesome for Steyer’s public image is the fund’s history of investing in fossil fuel projects, including a giant coal mine in Australia that generates vast quantities of carbon emissions.

The owners overcame protests by environmentalists and won permission to clear 3,700 acres of forest that served as a koala habitat and mine 12 million tons of coal per year. Steyer’s critics have long seen his past personal stake in coal mining as hypocritical.

“If you’re running as a liberal, idealistic candidate, as Tom Steyer is, it’s a serious problem when the story you’re trying to tell uses words like private prisons and coal,” said Jessica Levinson, a Loyola Law School professor. “It just goes directly against the rainbows and sunshine and clean air and better tomorrow narrative he’s trying to paint.”

Steyer said he left Farallon in part because of its holdings in fossil fuels. “I wish I’d made the move away from fossil fuels sooner,” he said.

Steyer, 62, muscled his way onto the public stage by becoming one of the Democratic Party’s top donors over the last decade. He put $74 million into the 2018 midterm election. He has carefully crafted his political profile around his spending to promote liberal causes, most visibly the fight against global warming and the drive to impeach President Trump.

Some of Steyer’s record has yielded bad publicity over the years as he weighed runs for elected office in California. But his entry into the presidential race on Tuesday and his vow to spend $100 million of his own money on his campaign will draw fresh scrutiny to the means he used to amass what Forbes estimates to be his net worth of $1.6 billion.

Steyer, who grew up on Manhattan’s East Side, started his career on Wall Street in the late 1970s at Morgan Stanley and worked later on mergers and acquisitions at Goldman Sachs. In 1986, he opened Farallon, which grew from $9 million to $36 billion on his watch, according to Steyer.

Some Democrats say Steyer has atoned for his sins. RL Miller, chairwoman of the state Democratic Party’s environmental caucus, was perplexed by his candidacy and said his money would be better spent advancing other Democrats.

“I do feel he has demonstrated substantial good faith in that yes, he made a lot of money from bad places, but he’s been very, very open about the fact that he’s turned over a new leaf and is no longer taking money from those bad places and is instead spending to do good,” Miller said.

The business records of wealthy candidates are often weaponized by rivals. Former President Obama cast GOP challenger Mitt Romney in 2012 as a ruthless plutocrat who made millions of dollars on corporate takeovers that put thousands of Americans out of work. Romney co-founded Bain Capital, a private equity firm.

Gray Davis won California’s Democratic primary for governor in 1998 after portraying rival Al Checchi as a tycoon who pillaged Northwest Airlines, firing thousands and forcing thousands more to take pay cuts.

“When these wealthy, self-financing first-time candidates want to throw their hat in the ring, whether they’re Democrat or Republican, they have to be prepared for a complete drill-down on how it is they made those millions of dollars,” said Garry South, who was Davis’ chief strategist.

As for Steyer, South said, “It’s pretty hard for me to see a billionaire on the Democratic side credibly take on the whole issue of wealth inequality.”

Tom Steyer joins swarm of Democrats running for president »

Within hours of Steyer’s announcement, two of his opponents took shots at him.

“I’m a bit tired of seeing billionaires trying to buy political power,” Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont told MSNBC.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, who is competing with Sanders for progressive voters, tweeted, “The Democratic primary should not be decided by billionaires, whether they’re funding super PACs or funding themselves.”

In an email seeking donations on Thursday, she said, “We need our candidates to compete to have the best ideas — not just to write themselves the biggest checks.”

Both Sanders and Warren, who frequently rail at what they see as unfair advantages for the super-rich, have declined to take money from Wall Street donors.

Steyer’s wealth will enable him to run more television ads than most of his opponents can afford. He is already spending $1.4 million on advertising over the next two weeks on national cable news networks and in the first four states to hold a primary or caucus.

“Maybe he feels he can overwhelm these questions by spending a lot of money telling his story the way he wants to tell it,” said David Axelrod, the architect of Obama’s campaigns. “The problem is in the presidential race, the coverage is so intense and social media such a big piece of that, these kinds of vulnerabilities get shared virally very readily, and I’m not sure you can overwhelm that, even with hundreds of millions of dollars.”

Steyer could also face questions about spending that much money on himself. “Does all that spending help in the end of the day or does it become an emblem of excess and self-aggrandizement?” Axelrod said.

Asked about his letter to Farallon investors on the British Virgin Islands company that was going to help them avoid federal taxes, Steyer did not address his past actions, but called for new taxes on the rich to reduce inequality.

“I use no offshore tax havens and pay all U.S. taxes in full,” he said. “I believe we should have a much simpler and fairer tax code and get rid of all loopholes.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.