The delegate chase: How the presidential nomination process really works

As the presidential primary race slogs on for both major parties, one thing has become increasingly clear: It’s not (just) about the voters.

Of course, candidates are chasing wins in the popular vote tallied in primary elections and caucuses. Just as crucially, though, they are seeking to rack up delegates to their party conventions, a related task that will actually determine who becomes the presidential nominees.

Understanding the delegate chase requires both vocabulary and math lessons.

Delegates are the party stalwarts, elected officials and grass-roots activists who represent their respective states at the national conventions this summer and vote for a nominee.

Though the Republican race has garnered more attention, the Democrats’ process is a more straightforward place to start.

Democratic delegate selection

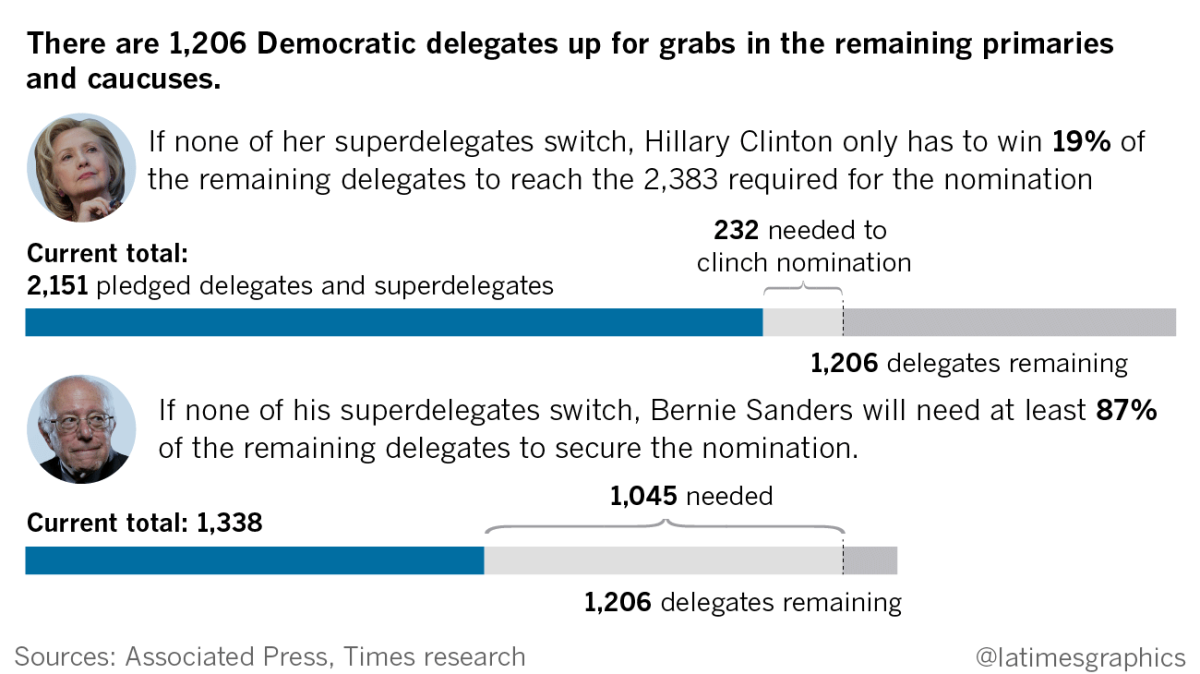

When Democrats convene in Philadelphia in July, 4,765 delegates will be present. The threshold for a majority is 2,383 delegates.

Democratic delegates are awarded proportionally in every state contest. For example, in the New York primary, Hillary Clinton won just short of 60% of the popular vote and got a corresponding 139 of the state’s 245 pledged delegates.

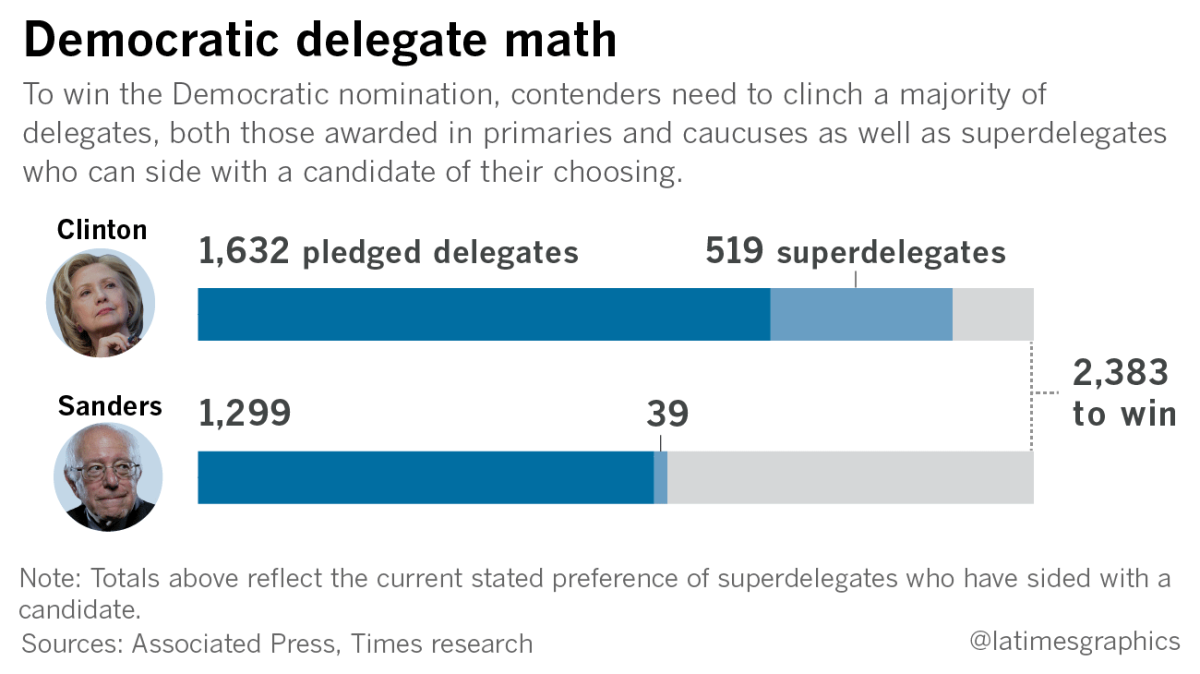

Clinton and rival Bernie Sanders are vying for two types of delegates: pledged and superdelegates. Pledged delegates cast their vote according to how their state voted. Superdelegates — a collection of 712 party leaders, elected officials and other high-profile Democrats — are allowed to vote for whomever they choose.

Superdelegates have been viewed with skepticism by some Democratic primary voters, particularly Sanders supporters, who fear the party establishment could tilt the nomination in Clinton’s favor and thwart the will of voters.

Election 2016 | Live coverage on Trail Guide | Track the delegate race | Sign up for the newsletter

But some in the Sanders campaign have slowly come around on trying to use superdelegates to its advantage. Campaign manager Jeff Weaver said on MSNBC this week his team would “absolutely” focus on flipping superdelegates who back Clinton to capture the nomination.

Overall, Sanders trails well behind Clinton with 1,338 pledged delegates and committed superdelegates, compared with her total of 2,151 , according to projections by the Associated Press.

It’s a misconception that “superdelegates are some nefarious group that don’t pay attention to the voters,” said Elaine Kamarck, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Since superdelegates were first used in 1984, “they have never yet turned aside the person who won the most votes in the primary,” said Kamarck, author of “Primary Politics: Everything You Need to Know about How America Nominates Its Presidential Candidates.”

Republican delegate selection

While the Democratic system is uniform, the Republican system is anything but.

“The Republican party practices a fierce federalism, which basically means that every state can do whatever it wants, and no two do the same thing,” said Ben Ginsberg, a Republican elections attorney.

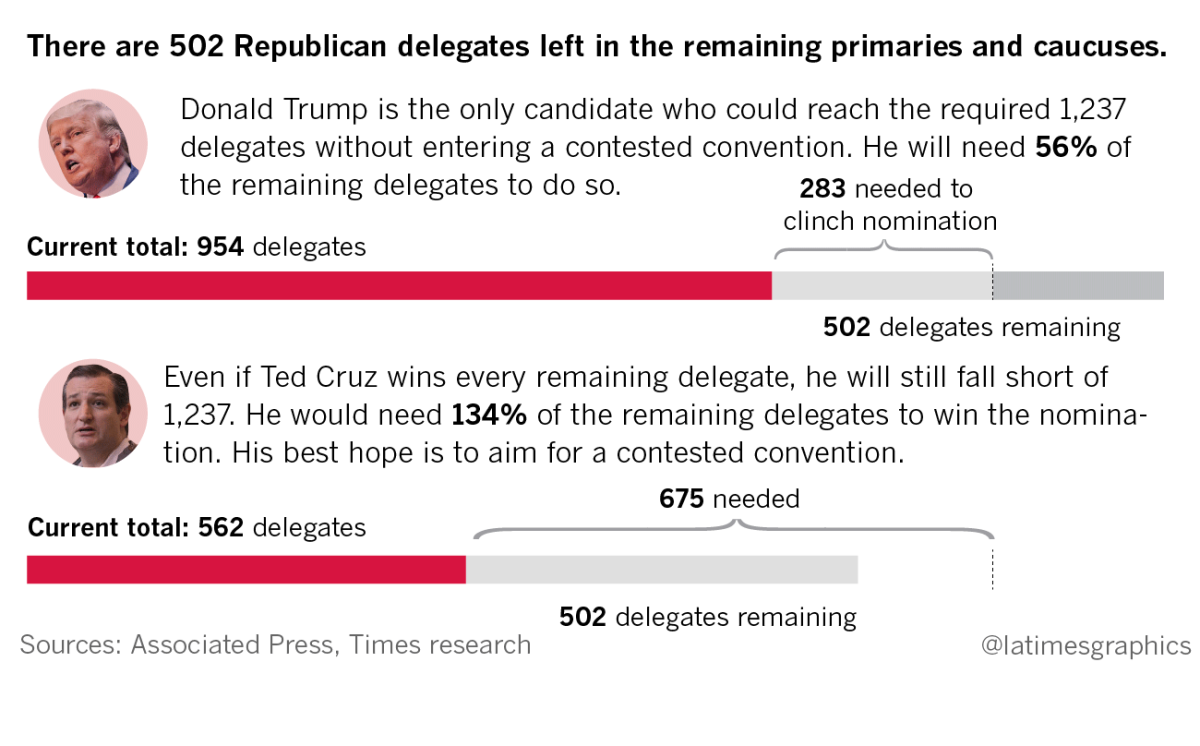

At the GOP convention in Cleveland in mid-July, 2,472 delegates will attend; a nominee needs 1,237 delegates to clinch the majority.

The result is a patchwork of rules governing the relationship between delegate allocation and voting results; some states are winner-take-all, while others award delegates based on results by congressional district.

Donald Trump leads with 954 delegates, and he insists he can reach 1,237 by the time of the final primary contests in June.

But his rivals, Texas Sen. Ted Cruz and Ohio Gov. John Kasich, who have 562 and 153 delegates respectively, insist no one will clinch a majority before Cleveland.

“We’re heading to a contested convention,” Cruz said the day after losing the New York primary. “Nobody is able to reach 1,237 [delegates].”

Most delegates must vote according to the results of their states primary or caucus on the first round of voting at the national convention.

But if no candidate secures a majority on that first ballot, some delegates no longer are bound to their states popular vote on subsequent ballots. Those delegates then can vote for whomever they choose.

That has put an intense focus on the individuals selected to serve as delegates often through a separate process from the primary elections. Campaigns are seeking to secure delegate slots for their supporters, should the convention require multiple ballots, and courting other delegates who are not yet committed to a candidate.

Seventy-three percent of delegates will be chosen on the local level: conventions or state executive and central committees, Ginsberg said. That puts an incredible organizational burden on each campaign to be able to keep track of individual delegates.

Cruzs campaign has stood out for its sophisticated delegate-tracking operation. In Georgia, for example, where Trump handily won the primary, Cruz loyalists have won delegate slots; while they must vote for Trump on the first ballot, theyre free to switch to Cruz after that.

Follow @melmason for more on politics.

ALSO:

Analysis: Who will play nice first: Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders?

After New York drubbing, Ted Cruz shifts his message to attract moderate GOP voters

UPDATES:

April 27, 1 p.m.: This story was updated to reflect the April 26 primary results.

This article was originally published at 3 a.m. April 22.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.