Opponents sue to overturn California’s new aid-in-dying law

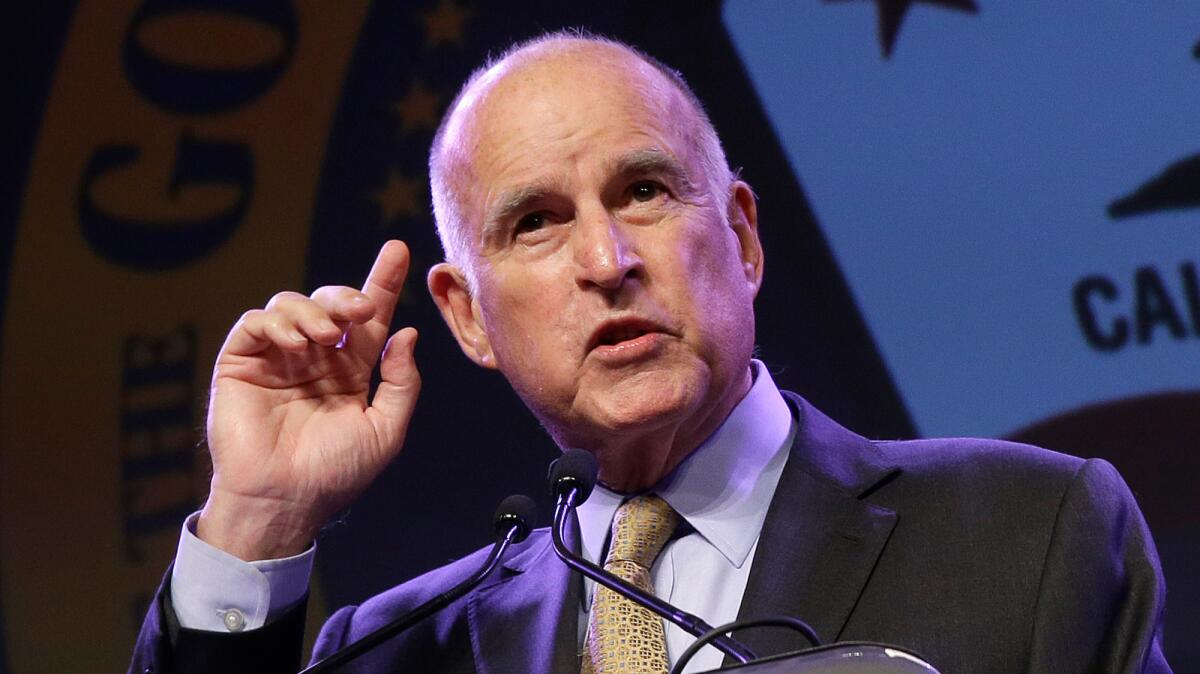

A group of physicians and others has sued to overturn California’s aid-in-dying law, which took effect Thursday. The measure was signed by Gov. Jerry Brown, above.

As a law went into effect Thursday allowing physicians to prescribe medicines to terminally ill patients to hasten their deaths, a group of doctors tried to overturn it in court.

The Life Legal Defense Foundation, American Academy of Medical Ethics and several physicians have filed a lawsuit in Riverside County Superior Court claiming that the state’s new aid-in-dying law is unconstitutional.

The End of Life Option Act allows patients with less than six months to live to obtain medicines from their doctor that would kill them. On Thursday, California became one of five states in the U.S. where the practice is legal.

Supporters of the law say it can help terminally ill patients avoid suffering. When he signed the bill into law in October, Gov. Jerry Brown wrote that he believed it would be a comfort to have this option if he were “dying in prolonged and excruciating pain.”

But the suit argues that California’s law is a civil rights violation, stripping terminally ill patients of protections afforded to other Californians.

Stephen G. Larson, an attorney for the plaintiffs, said that while it’s a felony in California to help or encourage another person to commit suicide, doctors under the law can legally do so for the terminally ill.

And, he added, California law says that when someone is a physical danger to themselves they should receive emergency help, including possible hospitalization and a mental health evaluation. But patients seeking doses of medication to kill themselves are not required to undergo a psychiatric evaluation, the lawsuit alleges.

“This is very arbitrary, very capricious, very ambiguous -- really no accountability,” Larson said. “This is not a good law.”

Patients seeking lethal medications under the law must have two physicians determine that they are mentally competent and terminally ill. If a physician has questions about a patient’s mental state, the patient must be referred to a psychiatrist for an evaluation.

Data from Oregon, the first state where aid in dying was legalized, show that 5% of patients who have died there using lethal medications had been referred for psychiatric evaluation.

Kevin Diaz, national director of legal advocacy for Compassion & Choices, which advocates for aid in dying, said he didn’t think the lawsuit would move forward.

“I just don’t understand exactly what their assertions are, given that this legislation treats all people ... no matter what their condition, equally, and is respectful of their end-of-life wishes,” Diaz said. “I don’t really think it has legs.”

A judge denied a temporary restraining order against the law Thursday, but a hearing for a preliminary injunction has been scheduled for the end of the month.

The coalition Californians Against Assisted Suicide along with the national Patients Rights Action Fund launched a website this week where patients and family members can report possible abuses of the law.

“Our hope is that we can provide this online vehicle for patients and families who may feel pressured by a daunting healthcare system, fear being a burden to their family, or are susceptible to suicidal thoughts when facing a seemingly hopeless diagnosis,” said Patients Rights Action Fund president JJ Hanson.

If the Legislature doesn’t choose to renew the new law, the End of Life Option Act will expire in 2026.

Follow @skarlamangla on Twitter for more health news.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.