Untutored Trump faces profound shifts in the international order

On the morning of Nov. 18, with a brass fanfare ringing through the high arches, I walked down the center aisle of the majestic Canterbury Cathedral to receive an honorary doctorate from the University of Kent. It was a crowning moment of my career, although a little voice inside my head was laughing uproariously at such a fuss being made about a cartoonist.

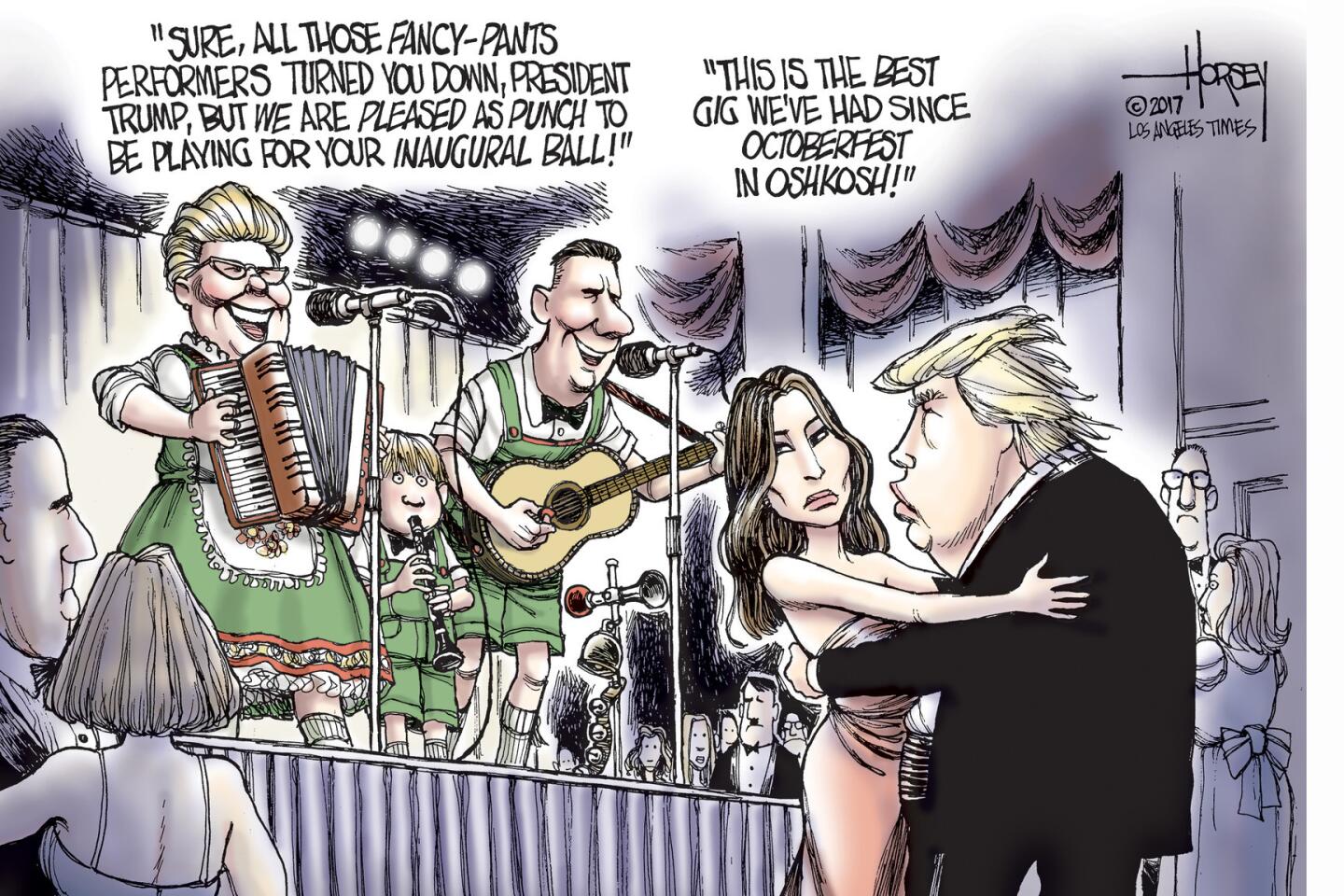

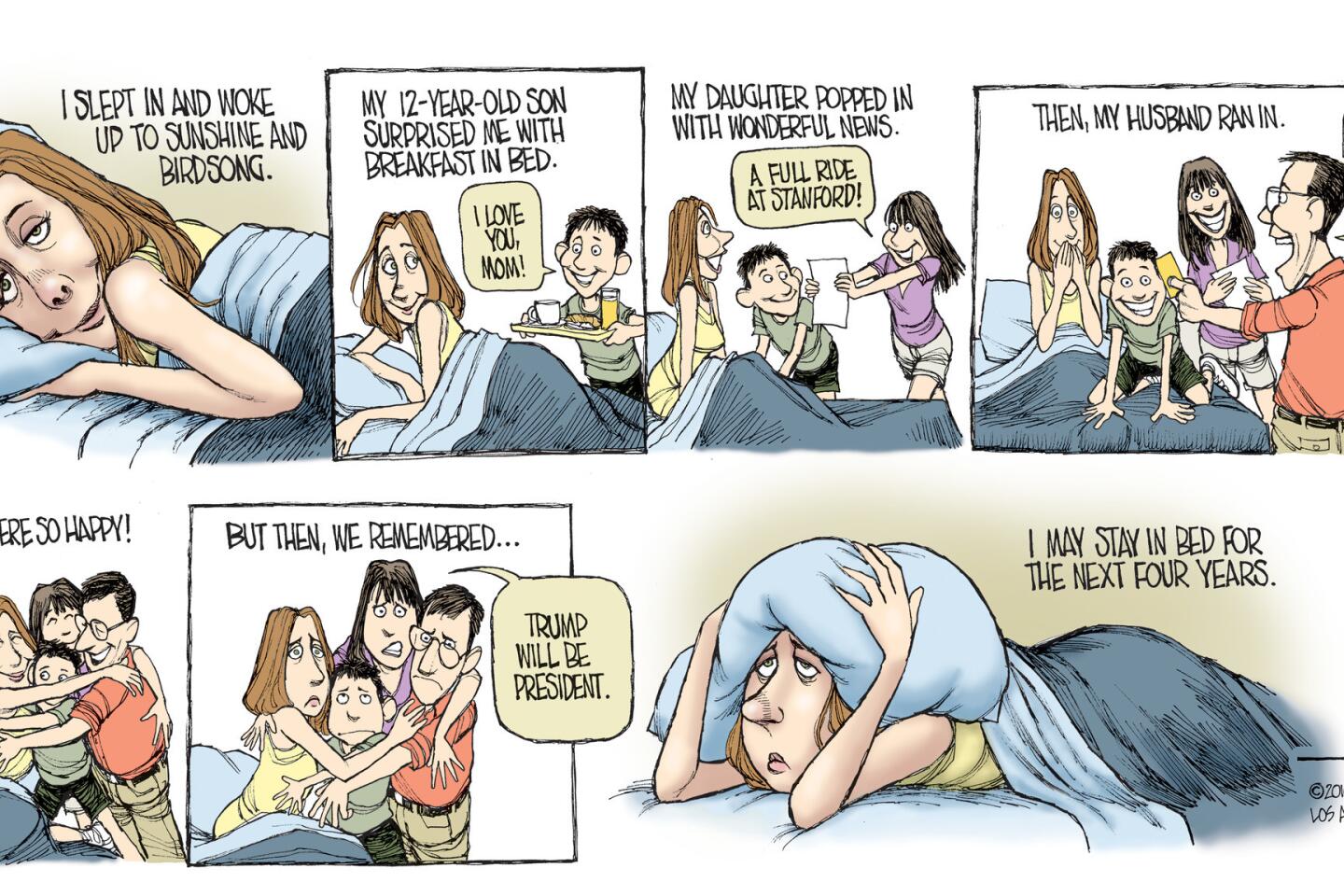

The 10-day trip to England to receive this accolade was a welcome break after long months of following an intense campaign that ended with the election of the stunningly unqualified Donald Trump as president of the United States. Of course, that topic could not be escaped. As soon as my family and I stepped off the airplane at Heathrow, a customs officer who just happened to be a young woman wearing a hijab made the first query about Trump.

My English friends, as well as everyone I spoke with during various events at the university, all wanted to commiserate about what Trump’s ascendance would mean for the world. They invariably compared the unpredicted Trump victory with the unexpected approval of Brexit last June when working-class and rural voters said yes to withdrawing the United Kingdom from the European Union. In one way or another, everyone was asking: What in the world is going on?

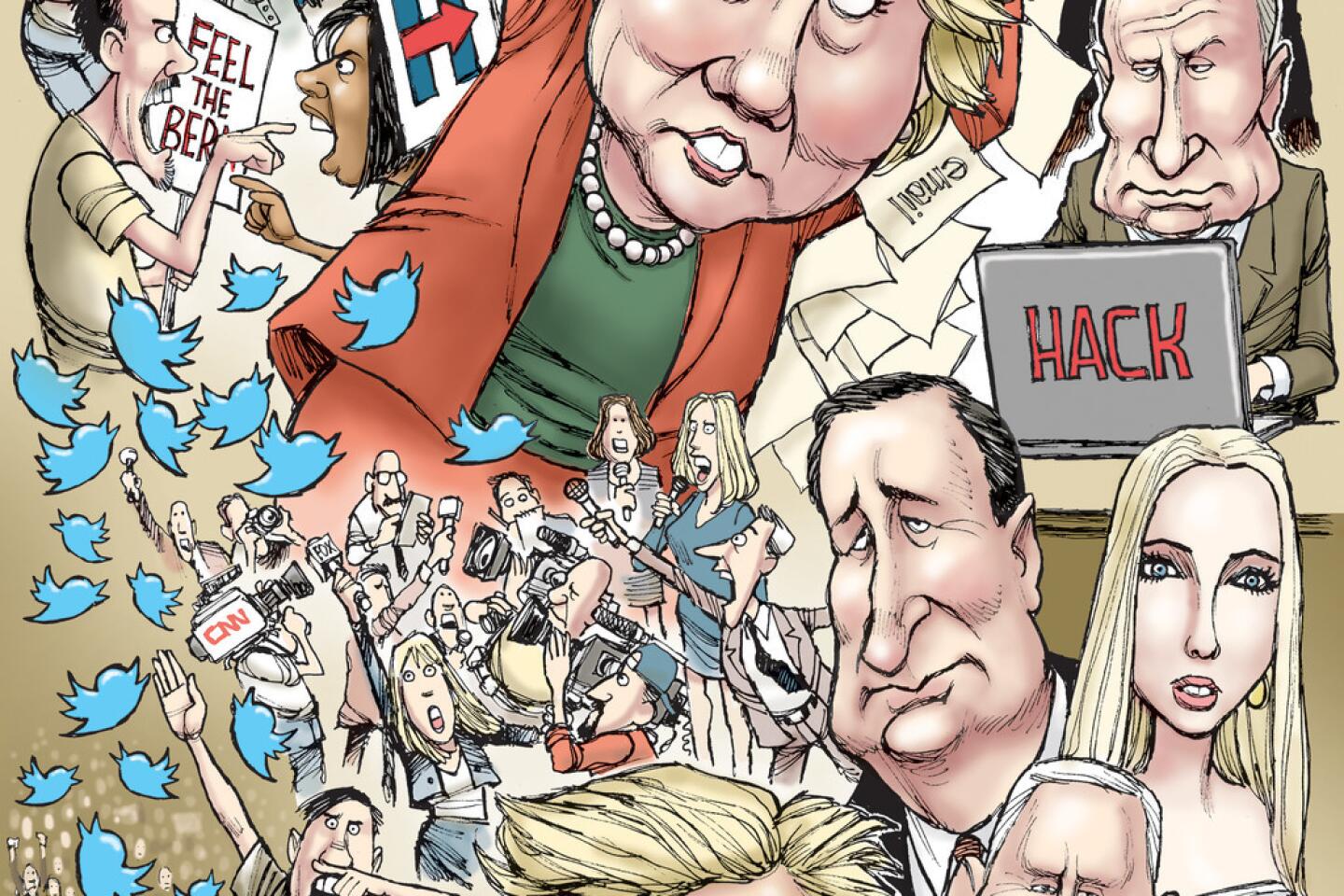

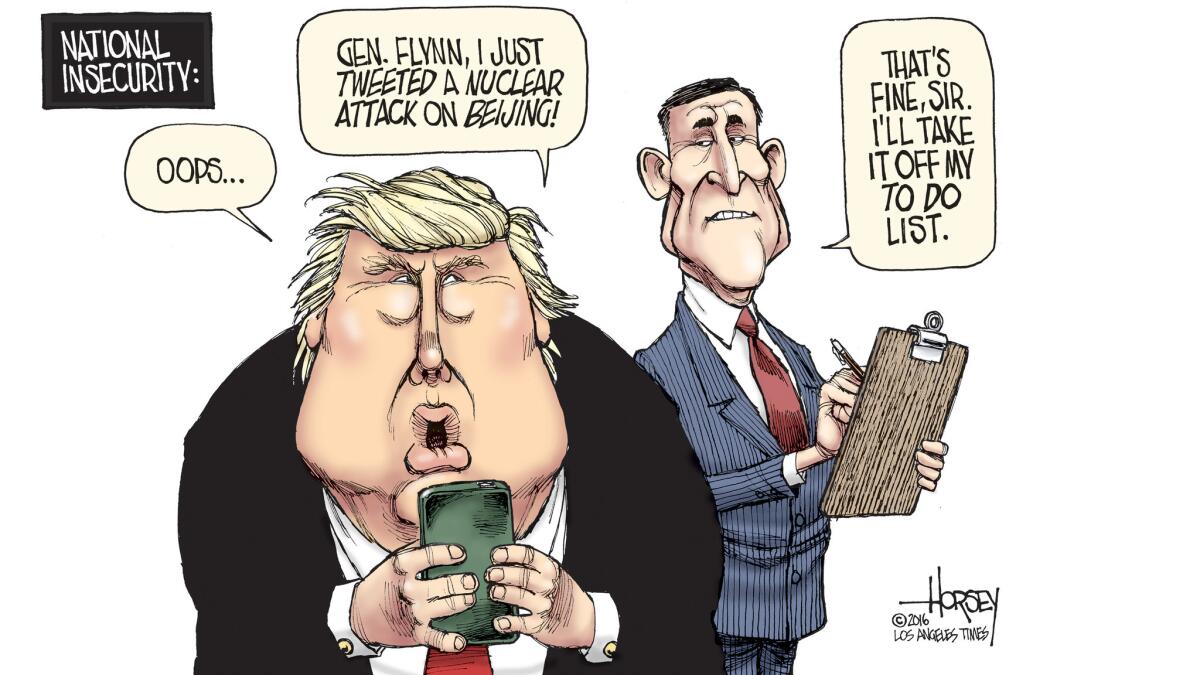

When I attended the University of Kent at Canterbury as a master’s student in international relations 30 years ago, that was the prime question at the core of all lectures, discussions and debates. How do we understand the world and how it works? My return to campus in November was a useful reminder that a deep understanding cannot be deduced by chasing every tweet sent out by a president-elect or by watching campaign surrogates shout at each other on CNN.

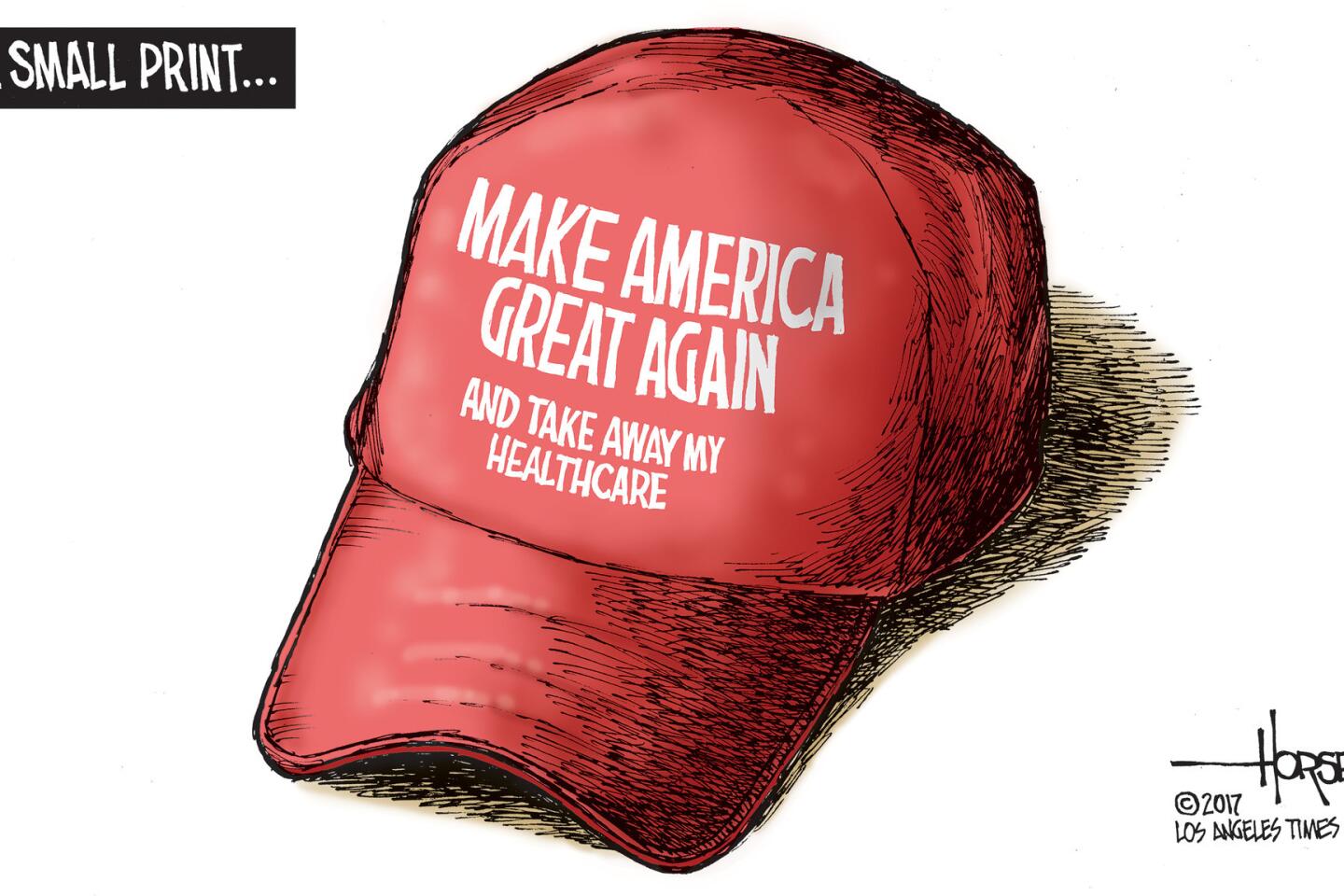

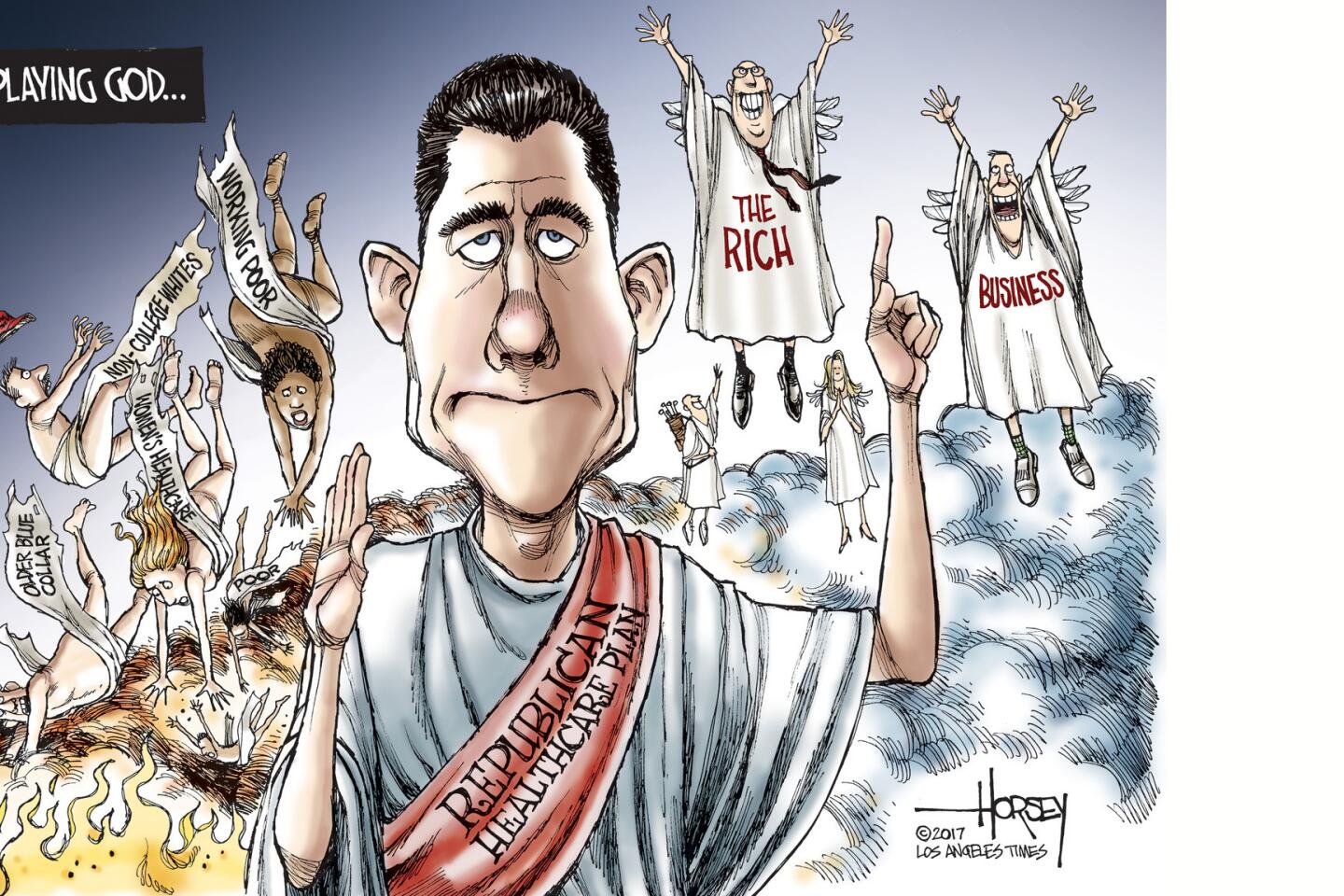

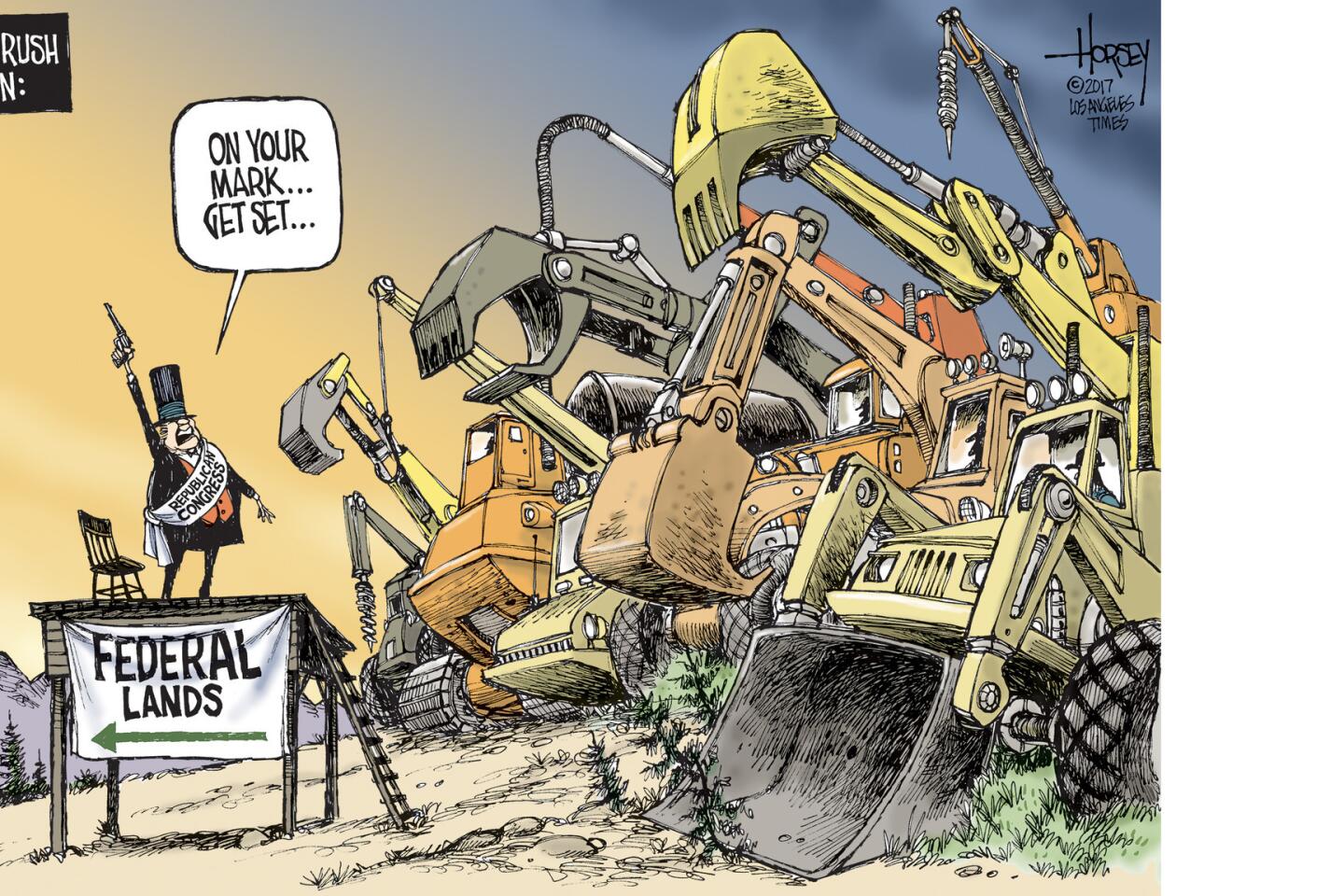

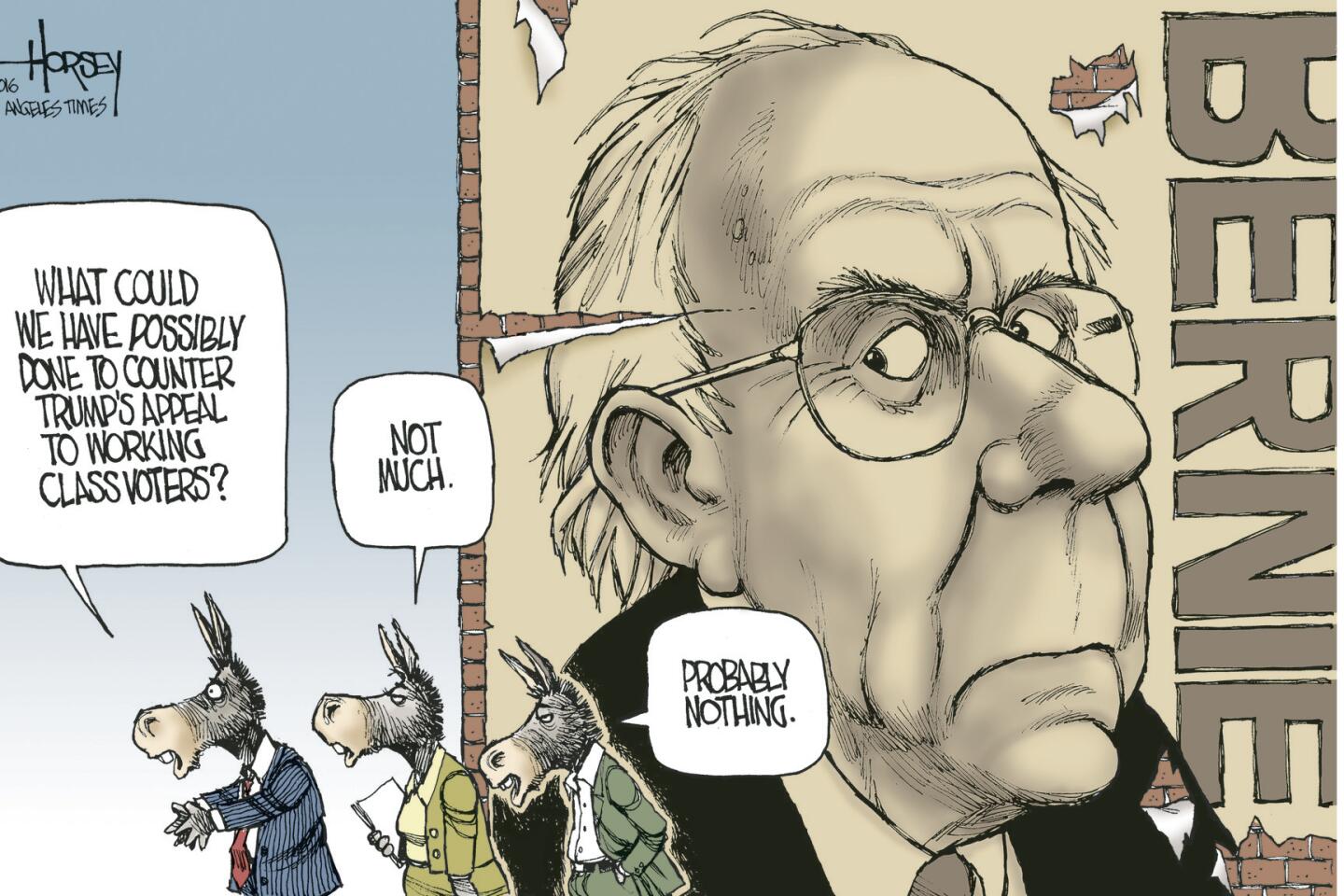

The disaffection of certain classes of voters in the United States and Europe that led to Trump’s win and the thumbs-up for Brexit — and which may lead to further rejections of the established order in Italy, Germany and France in the coming year — is part of something bigger. You would never know it from the narrow scope of coverage on American cable news or most media outlets, but we are very likely at the edge of a dramatic shift in the entire world order.

Such transitional times have come before. The defeat of Napoleon in 1815 set the stage for a multipolar international system with the British Empire more or less at the top. The advent of the Great War in 1914 rocked that system to its foundations, though it held on until it was completely demolished by the Second World War. After 1945, we lived in a bipolar world divided between the United States and the Soviet Union. Then, in 1989, the Soviet empire disintegrated and the planet was left with one pre-eminent power, the U.S.

What we are experiencing now is a realignment away from that temporary unipolar reality. But what is coming next?

In a recent lecture, Trine Flockhart, professor of International Relations at Kent, made the case that we are not reverting to a multipolar system like that of the 19th century. Back then, the various Great Powers — Britain, France, Germany, Russia, America — generally shared a common idea of how the world should be ordered. From that evolved the economic and political environment Americans and Europeans have enjoyed for many decades; an order in which liberal democracy and free market capitalism were assumed to be the default goals of all humankind.

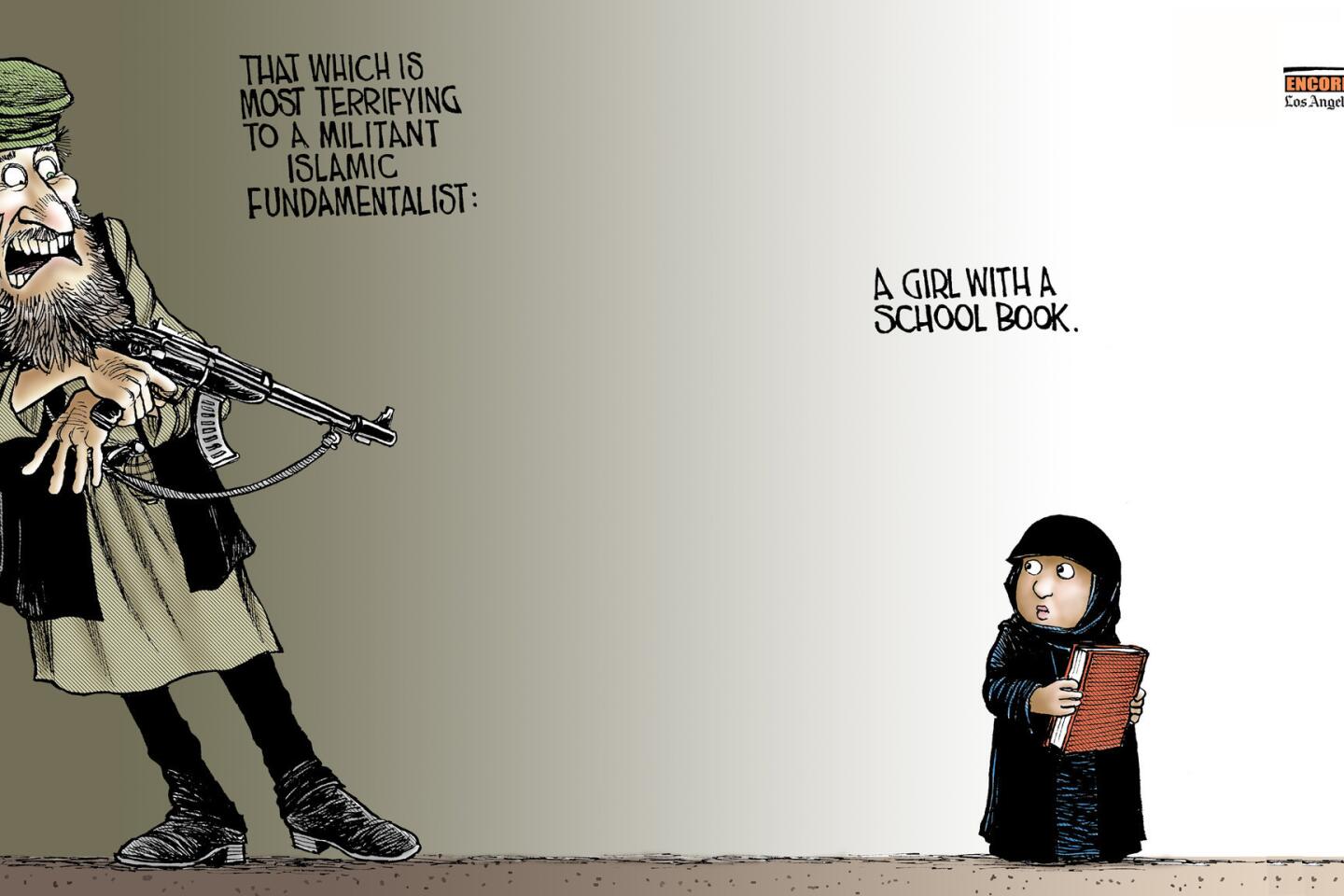

Flockhart contends we can make that assumption no longer. She sees something new, complex and discordant on the horizon, a future where there will be not just one world order but several. The authoritarian, centrally-designed capitalism of China and other Asian states will offer an alternative to the West’s liberal vision, as will the theocratic, culturally conservative Muslim regions, with Iran in particular challenging what has been the international status quo.

“For the West, who after all, has been the main instigator, the main owner and beneficiary of the liberal international order, the change is going to be especially unsettling because it basically ends 200 years of continuous expansion of the liberal international order,” Flockhart said.

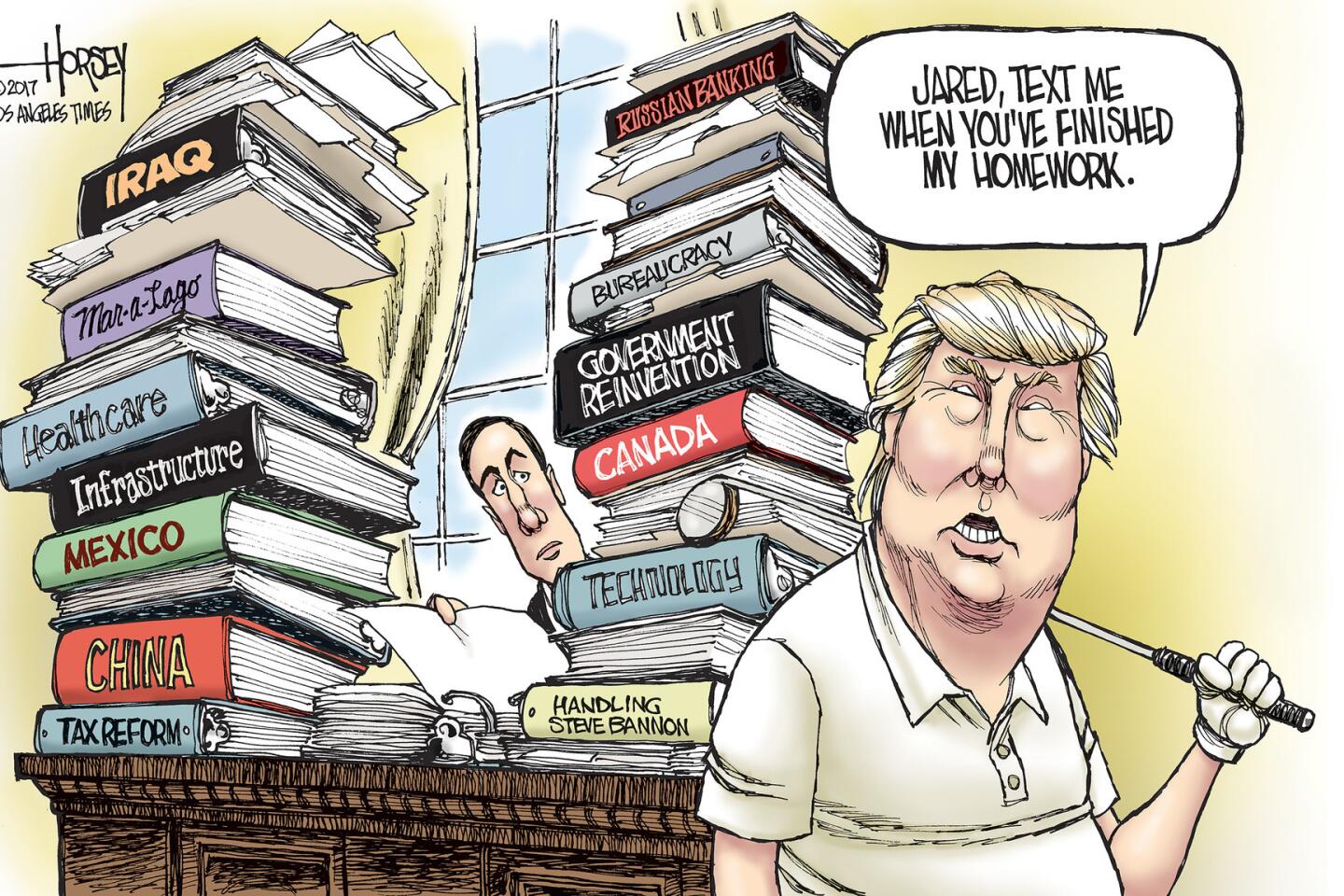

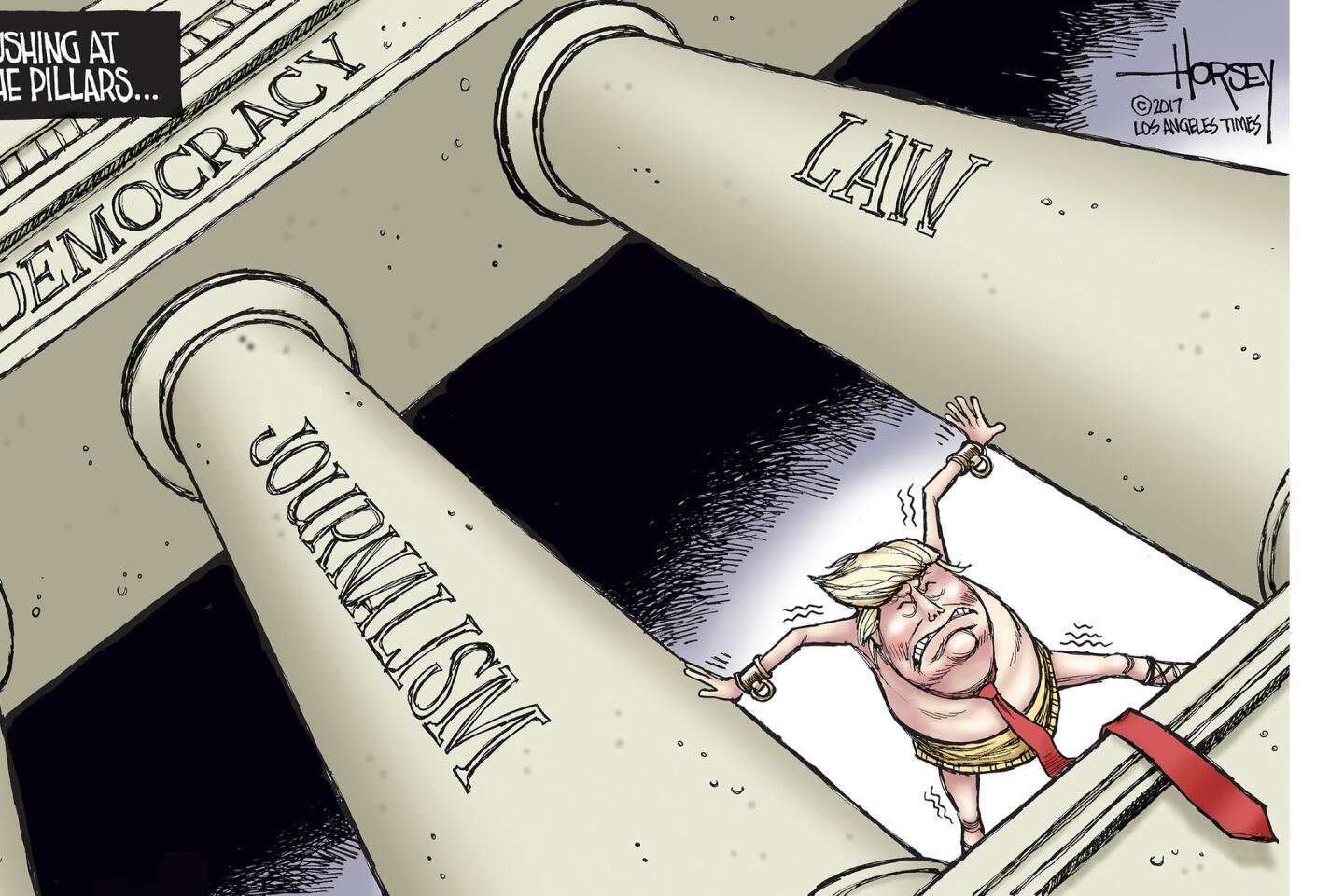

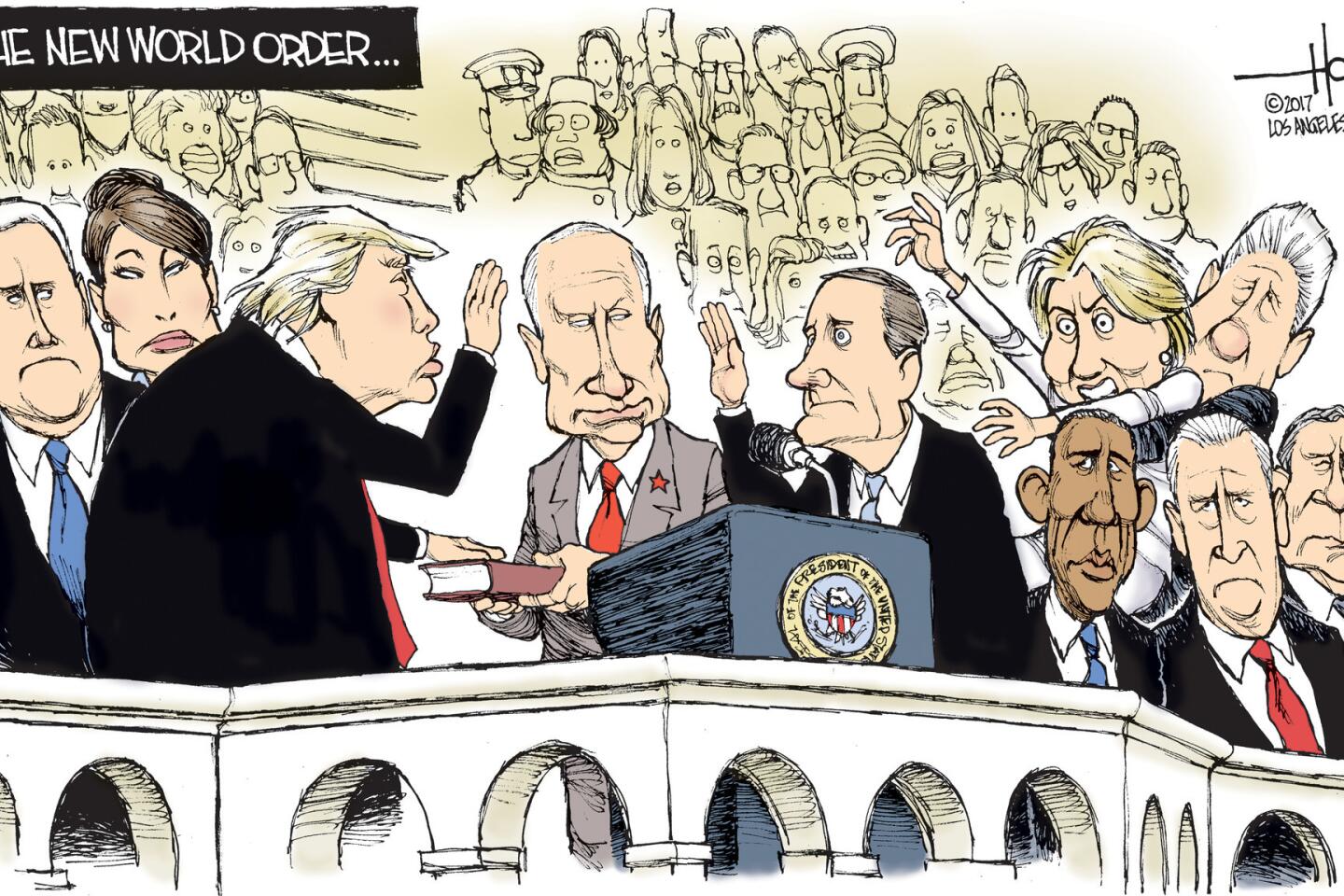

It is particularly disturbing that, as we are poised on the cusp of this great change, the two most influential and comparatively enlightened powers of the last 200 years, the United Kingdom and the United States, both may be retreating from the international stage. The withdrawal from Europe could sharply diminish British influence. In the U.S., the choice to elect to the presidency an untutored nationalist with only the dimmest understanding of international relations may make America an undependable, erratic outlier just when competing powers with very different conceptions of order are rising.

At the University of Kent, I learned the value of trying to perceive the full complexity of world affairs. Unfortunately, increased knowledge can also bring an increased awareness of looming calamities and the cost of ignorance at the top.

Follow me at @davidhorsey on Twitter

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.