Americans need to know all our history: the good, the bad and the complex

I am spending the Fourth of July in my hometown, Seattle, where, exactly a century ago, the Hiram Chittenden Locks opened with a boat parade and predictions that the new waterway connecting Lake Washington to Puget Sound would turn the upstart town into the biggest port on the West Coast. Los Angeles rose up to grab that title for itself, but Seattle hardly shrank into obscurity.

Currently, Seattle is the fastest-growing city in the United States and home to numerous world-changing companies. One way to write the history of the city is to say the ambitious, far-sighted spirit that built the locks opened the way for Boeing and Microsoft and Starbucks and Amazon in the following years.

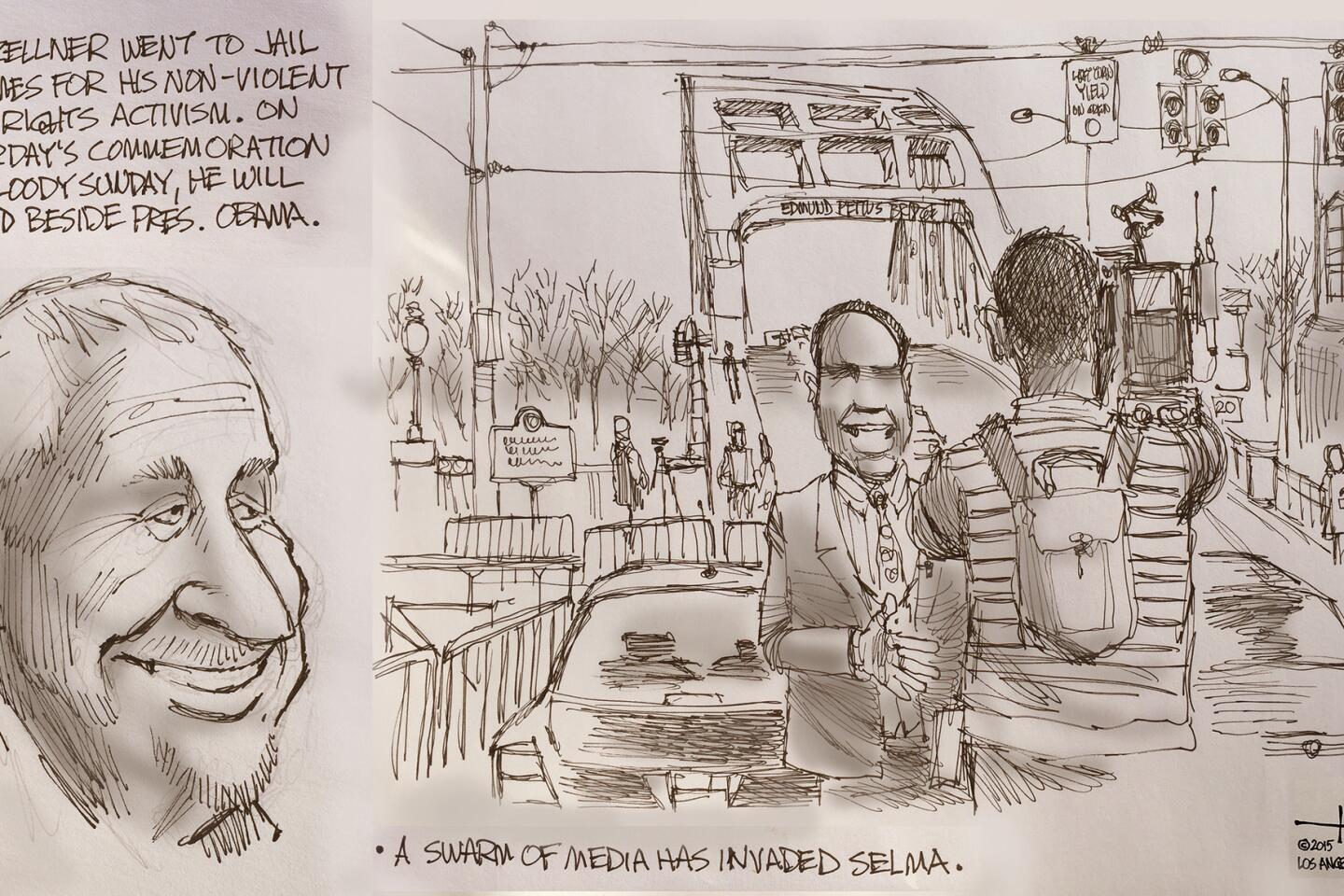

There is another way to tell the story, though, by looking at the same events from a different vantage point. Back one hundred years, there were still native Americans living on the edges of the city. One tribal group, the Duwamish, was settled on the Black River at the south end of Lake Washington where there was an abundant salmon run. When the locks and the connecting ship canal were opened, the level of the lake dropped nine feet as its water ran in a new direction toward the sea. The Black River dried up, the salmon run disappeared and the Duwamish were, once again, dispossessed.

In every part of the United States, history can be recounted with similar positive and negative contrasts. In downtown Los Angeles, there is a large stone memorial that I pass while driving to the LA Times building. The monumental bas relief sculpture depicts a group of U.S. soldiers raising the Stars and Stripes for the first time in the village of Los Angeles. That was 170 years ago on Independence Day 1847. Looked at one way, this epic art celebrates the inevitable advance of the American nation to the Pacific. Looked at another way, it commemorates an aggressive conquest of territory that rightly belonged to Mexico.

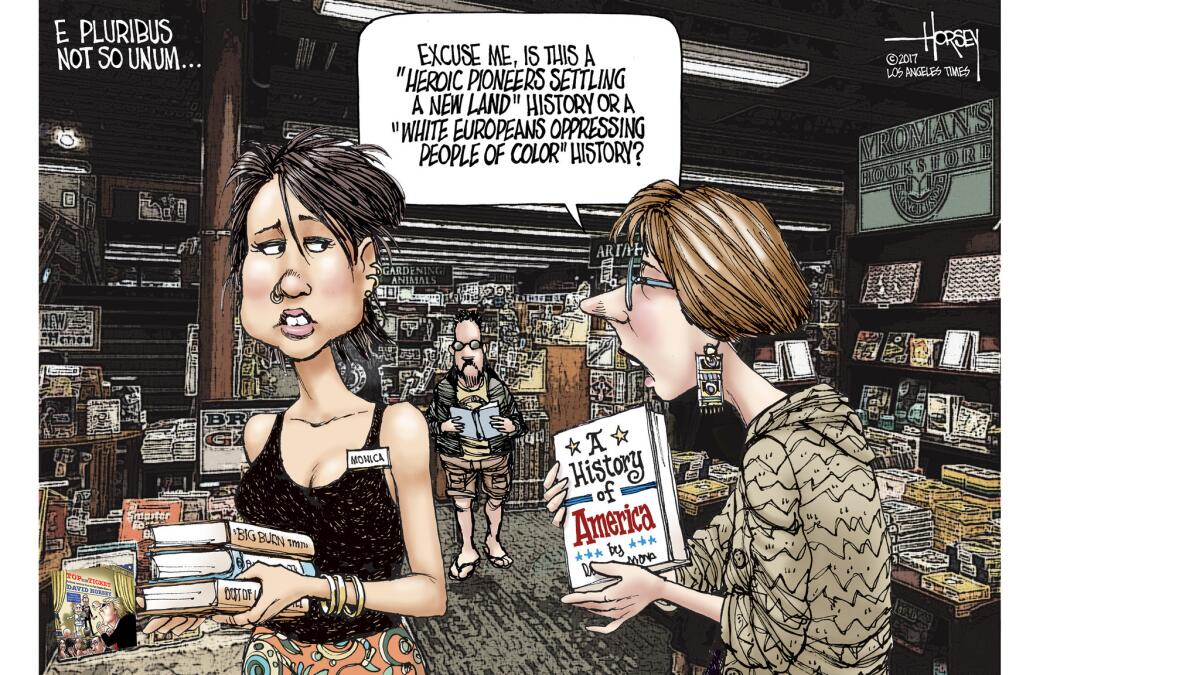

When I was growing up, the history I learned was much the same as it had been taught in American schoolrooms for decades. The mostly uplifting, positive story was told East to West, from Plymouth Rock to Daniel Boone’s Kentucky to bold settlers and brave cavalrymen settling the Great Plains to the California Gold Rush. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were great men who founded the greatest nation on the planet. Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves after a tragic civil war in which men on both sides fought for cherished principles. The nation grew into an industrial powerhouse, thanks to men like Carnegie and Rockefeller and inventors like Alexander Graham Bell, Thomas Edison and the Wright Brothers. Americans saved Europe in the First World War and saved the world in the bigger war that followed.

Today, in a growing number of schools and colleges, that history has undergone substantial revision.

The story now starts with indigenous tribes displaced and decimated by a relentless tide of European invaders. It tells about the violence that came after the peaceful first Thanksgiving meal. Washington and Jefferson are singled out as owners of slaves. The Civil War is seen more sharply as a moral battle to defeat an evil system of human bondage. Lincoln’s less-enlightened views on race are noted. The industrialists are unmasked as suppressors of the rights of workers and despoilers of the environment. World War I is portrayed as a monumental failure of an archaic ruling class. World War II is seen as a less-than-pure crusade, with Japanese American citizens locked up in prison camps, imperiled Jewish refugees turned away and atomic bombs incinerating entire cities.

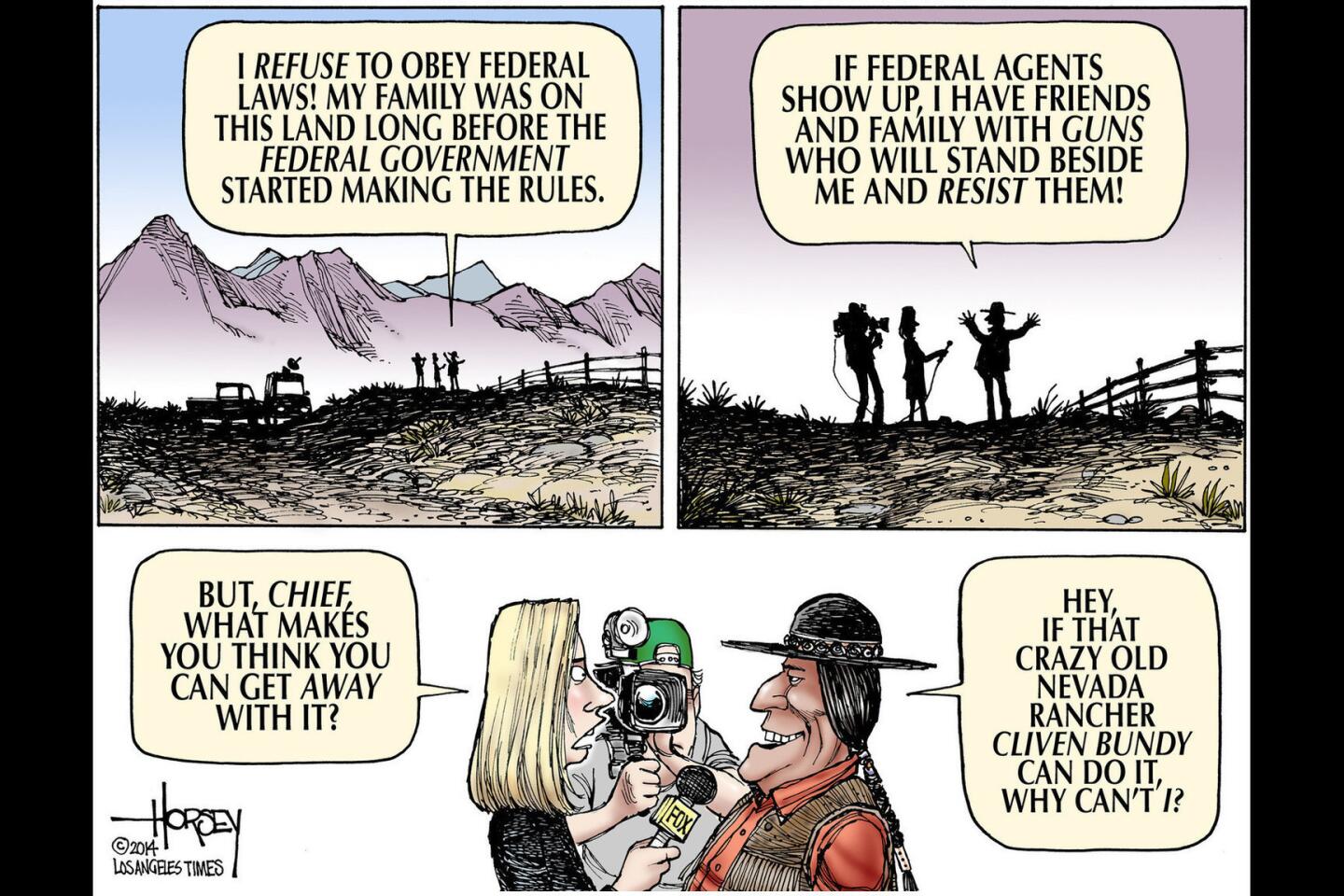

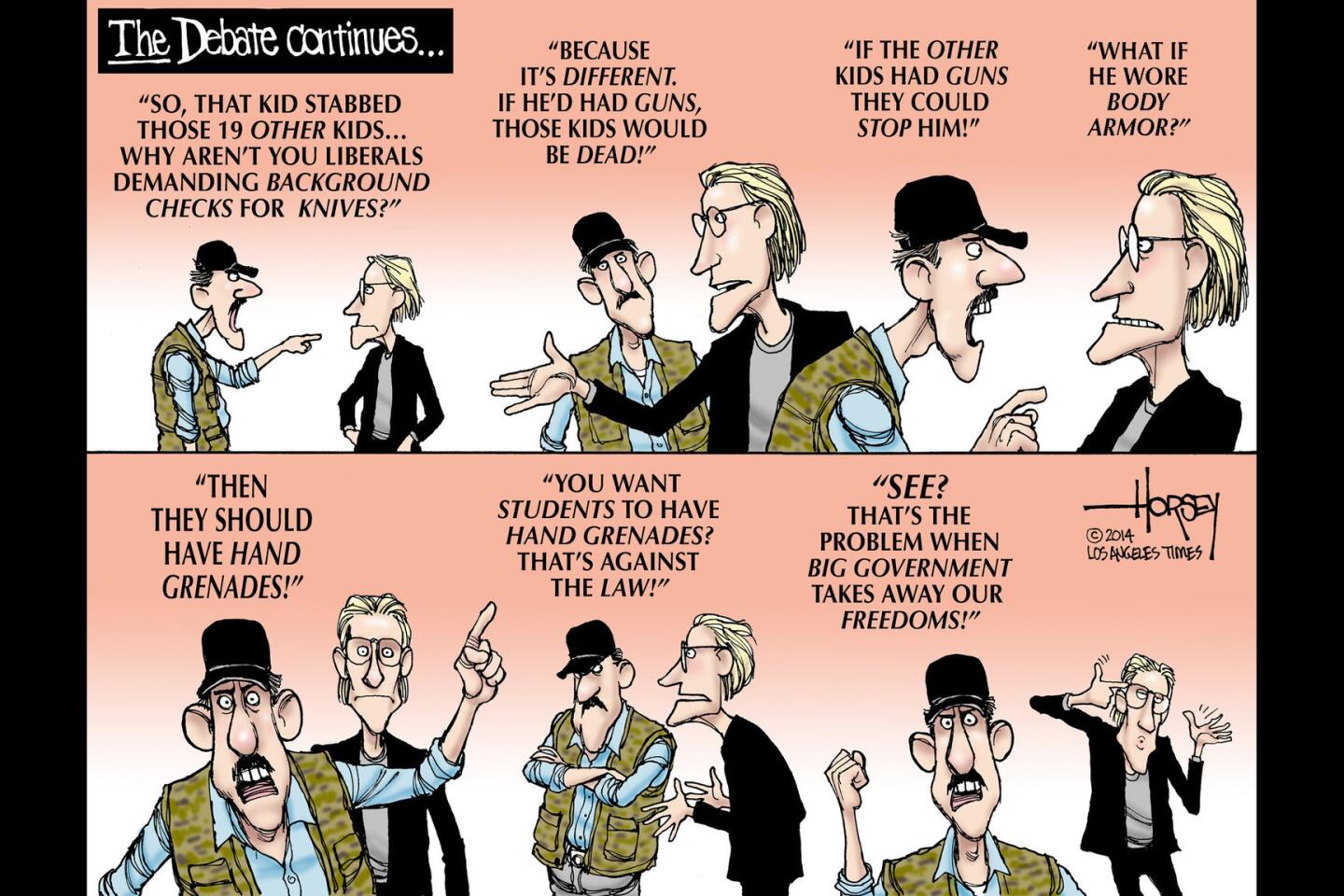

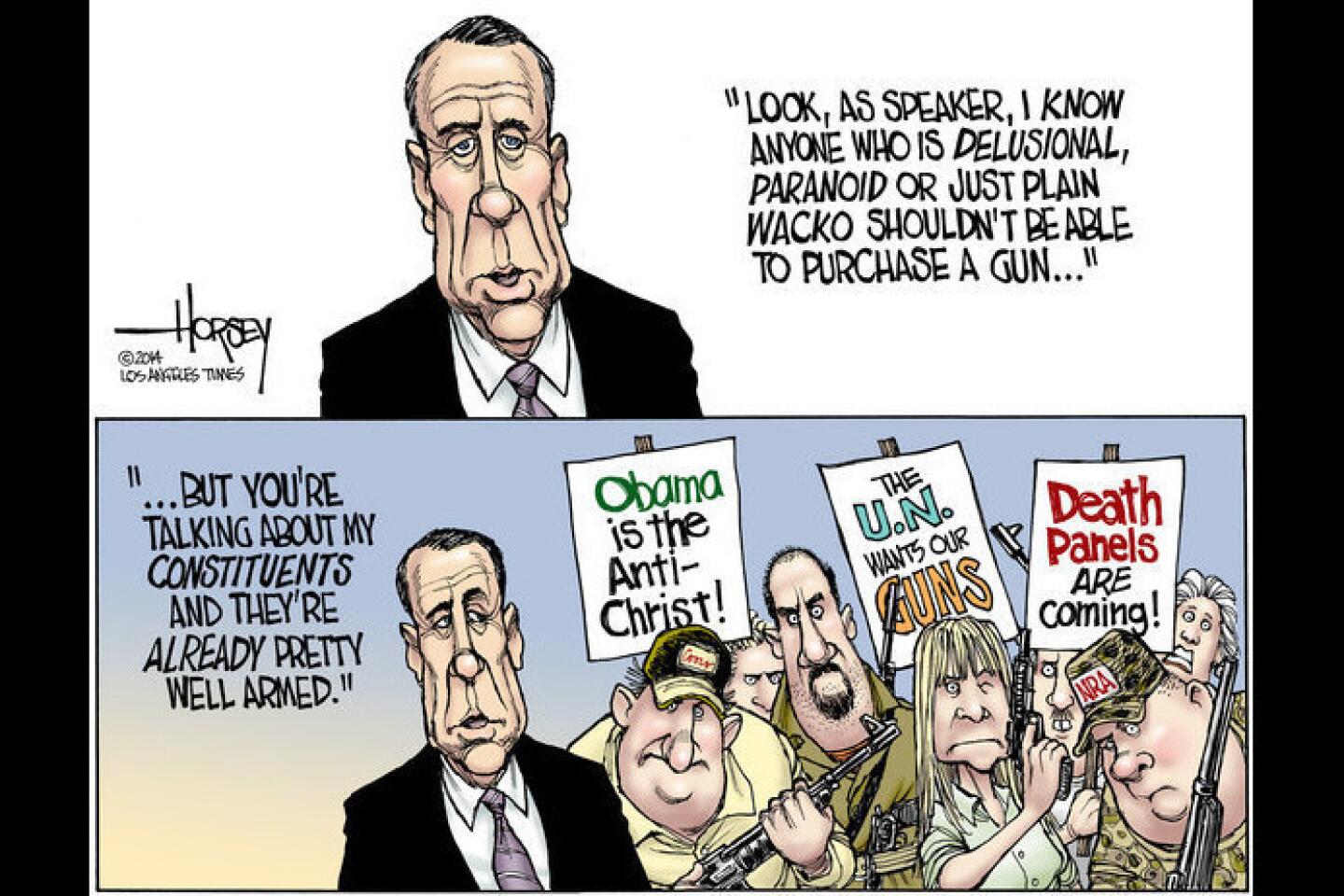

School boards and legislatures in more conservative regions of the country have pushed to keep the American history that is taught close to the old version. The contention is that new generations of Americans need to understand this is a nation with a profound destiny. American kids need heroes and inspiration, not cynicism and doubt, the argument goes.

In progressive communities, on the other hand, there is agitation for teaching a more inclusive history. This movement says the stories of immigrants and women and slaves and factory workers need telling; that white kids need to understand what their ancestors may have done to oppress people of color so that they can understand the source of their own privilege; that nonwhite kids need to know how their forebears were denied the right to vote, to own a home, to run a business, to feel safe walking down a city street.

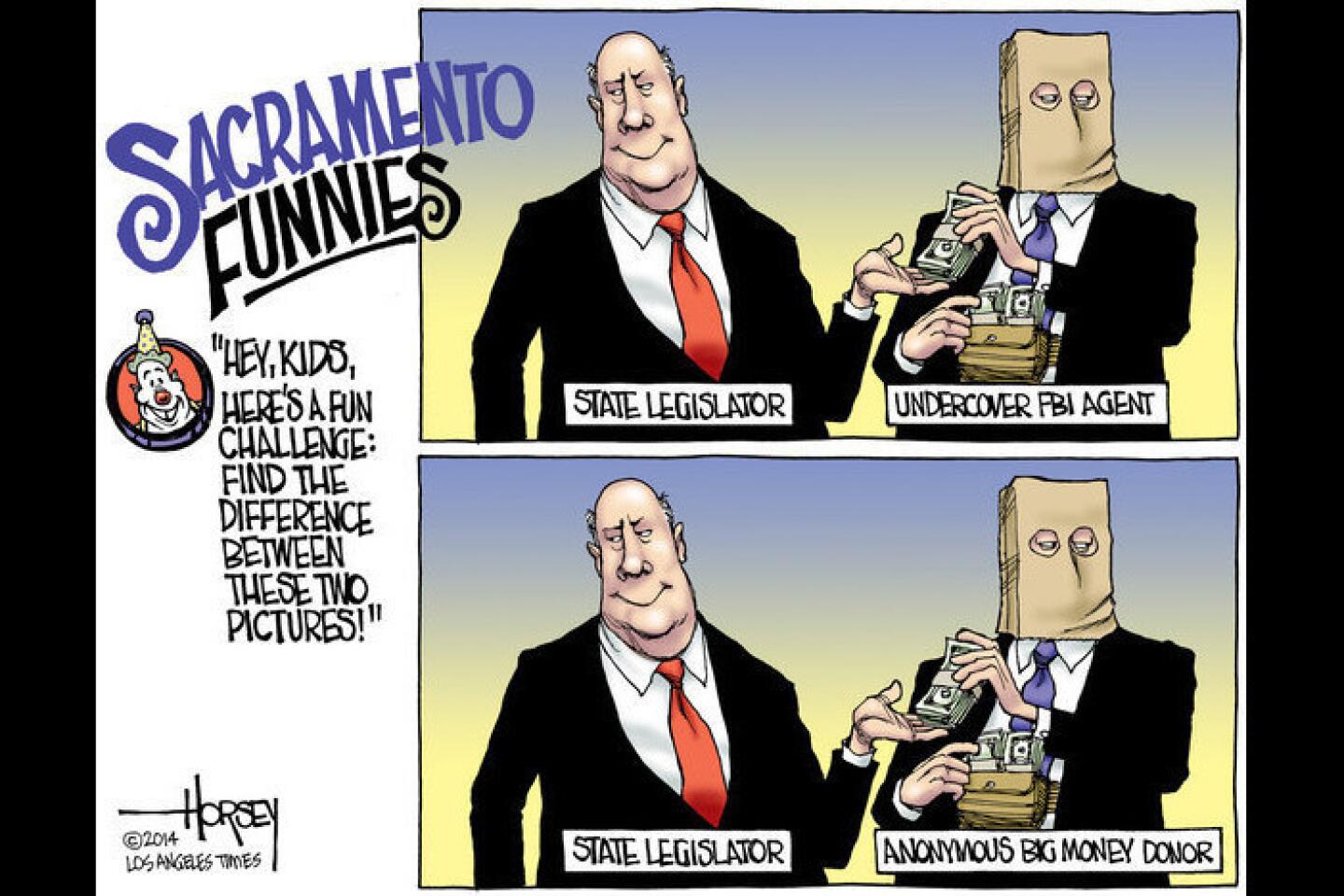

In these disquieting times when Americans are splitting in opposite directions, it is no surprise that our history, too, has become a field of dispute. Our shared sense of belonging to one nation is endangered, though, if we cannot find common ground in telling the epic tale of our republic.

We need to embrace the complexity. American history is not just a glorious panorama of heroic quests and grand achievements, nor is it just a dismal sequence of exploitation and racial strife. It is both of those, and much, much more.

An ignorance of history can prove fatal for any country. A narrow understanding that only reinforces biases and supports political factions is not much better. Americans need to know the entire story of who we have been — the good, the bad and the complex. That is how we perfect our union. That is how we make one nation from many.

Follow me at @davidhorsey on Twitter

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.