Commentary: Why aren’t all California elementary school students learning science?

As a student teacher I witnessed extreme inequalities in how science is communicated and taught at California elementary schools.

My first teaching experience was as a STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) education fellow in a program Cal Poly Pomona hosted during the 2022-23 school year. This program matched STEM majors with low-income elementary schools in hopes of exposing the students to more science. I started out excited about all the ways I was going to make science cool for the second-graders in my class. I was naive.

My 7-year-olds were experiencing their first year in a classroom due to the pandemic and were so behind. They needed basic writing and math skills, and classroom etiquette too. It was a constant balance between catching up and trying to implement new district mandates such as using i-Ready, an educational computer program that is pointless when your kids cannot even spell their names yet. During that fellowship, I taught just one science lesson.

The latest test scores for L.A. students are encouraging — but not yet time for a full-throated cheer because they are still below pre-pandemic levels.

One year later I was back in the classroom taking on the role of science educator in elementary after-school programs at low-income schools. Every week I went to different schools in Orange County to teach basic science lessons, but even with rotating sets of students I noticed a recurring theme. They had little to no science education during their normal school day.

This raises a major concern that not every student is receiving the same quality of education they need to be prepared for 21st century jobs. A study by the Public Policy Institute of California found that science education became a lower priority during COVID-19 restrictions, though it had been an issue long before because of underinvestment.

California does have guidelines for teaching science and expectations of what all K-12 students should have learned by the end of each school year. But the state doesn’t police schools to make sure they are following the guidelines, nor does it test for proficiency.

Proposition 28 directs nearly $1 billion to expand arts and music classes at California schools. But critics say some districts, including LAUSD, are using the budget bonanza for other things.

I have talked with different elementary school teachers about their experiences, and I am happy to report that the lack of science education is not happening at every school in California. The quality of education on subjects outside of language and math really depends on the school districts and the efforts of school boards and principals. This is not fair. All elementary students should be exposed to science curriculum regardless of what school they attend.

It’s not a California problem. Educators have been working to address this problem nationwide. Jill Grace, the director of the K-12 Alliance, said that historically the United States has prioritized language arts and mathematics, and without laws that specifically mandate science or other subjects, it is easy for elementary and middle schools to skip this curriculum.

“In California we have a system that includes an accountability dashboard, and until now the only content areas that faced accountability had been language arts and math,” Grace said. “Also, our Department of Education doesn’t have content departments, while some states do.”

Universities were never meant to be merely career-prep schools. But more universities are shrinking non-STEM departments.

Fortunately, starting next year the state’s education dashboard will include science assessments, which could put a spotlight on science education at California’s schools. And in the last school year, $85 million was allocated to help schools teach math and science. Though funding has been considered to be the root of this issue, teachers also need training to feel confident to teach science.

Maria C. Simani, the director of the California Science Project, has also been following this issue closely and hopes that the state Department of Education will prioritize training teachers for science. Simani estimates it would take teachers at least three years of training and support to begin adequately teaching science.

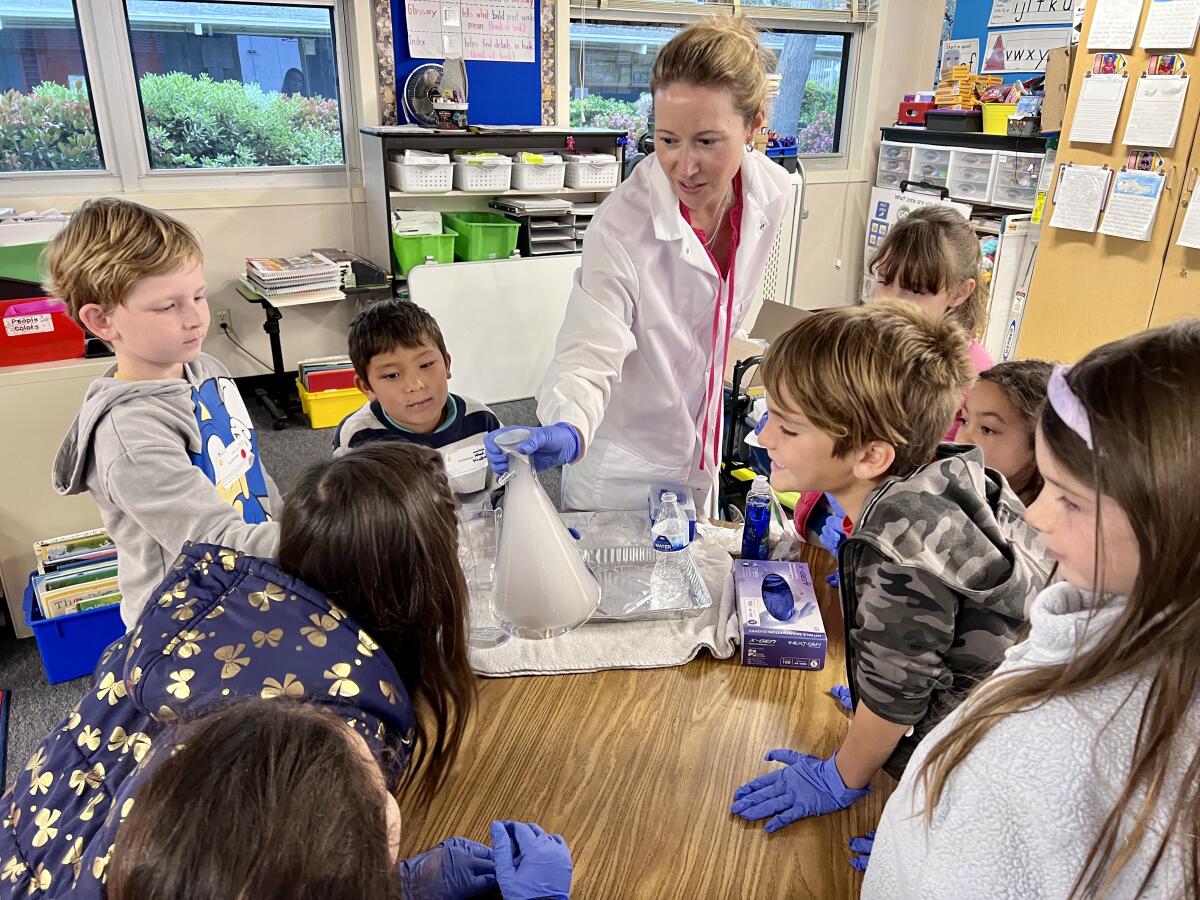

Science education is not difficult to implement, especially when the target group is young children. From my experience, kids are excited to learn when the lesson is hands-on and they can make mistakes and learn from them.

I was luckier than many public school students. I had amazing teachers throughout the West Covina Unified School District who were able to provide a well-rounded education that included life sciences and chemistry. I remember my elementary school having science festivals where different grade levels would prepare a project and share it with the school — this is where I found my love for science. I just hope that one day elementary schools will be a place where other students will find that same passion.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.