How humans’ loneliness epidemic extends to other species and natural phenomena

Book review

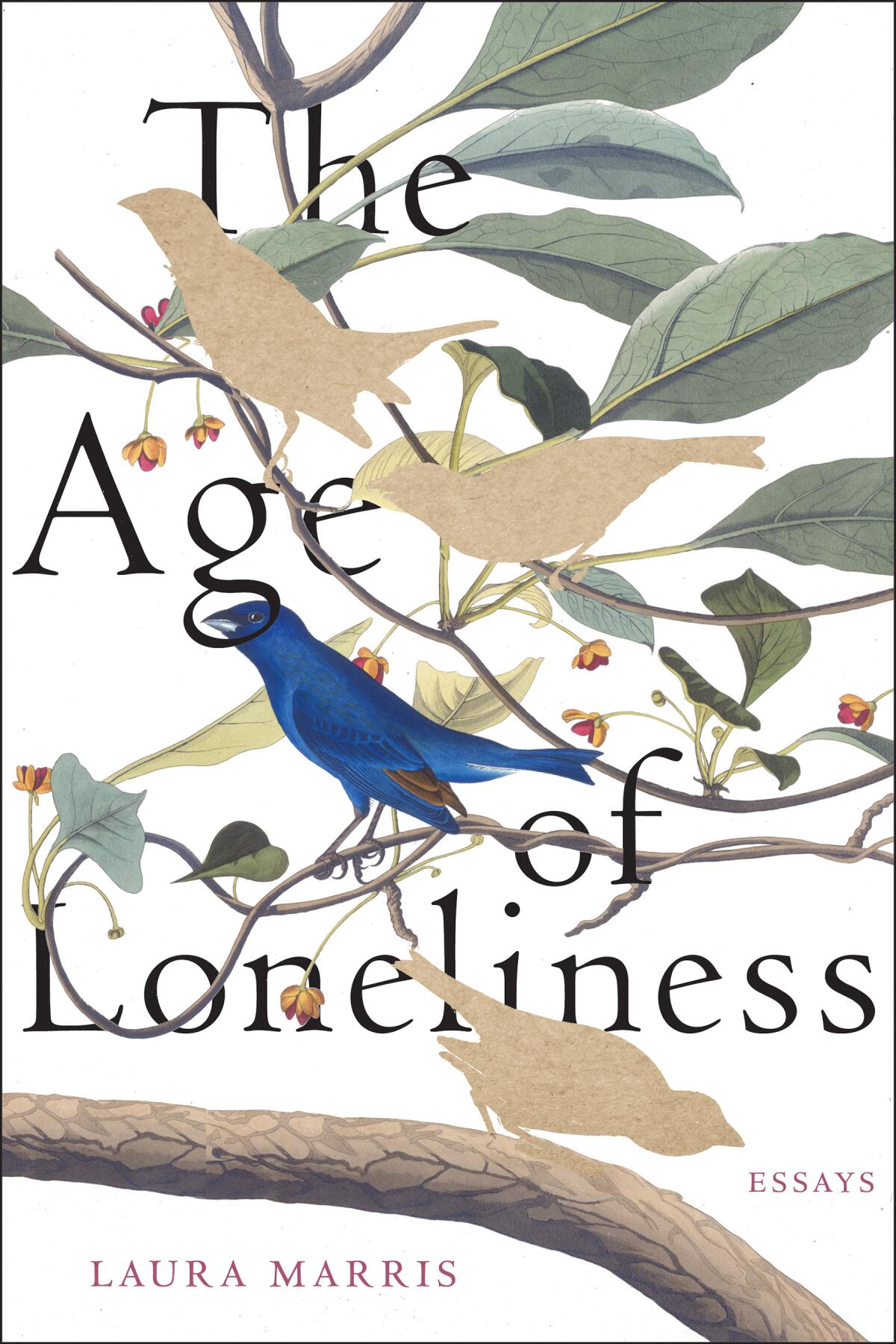

The Age of Loneliness: Essays

By Laura Marris

Graywolf Press: 208 pages, $18

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Earlier this year, an International Union of Geological Sciences committee voted against adding the Anthropocene, the human epoch, to Earth’s geological history. We are still, according to those scholars, in the Holocene, an age that began 11,700 years ago when ice sheets melted. Scientists in other specialties might disagree and point to planetary changes wrought by humans since before the mid-20th century; some believe humans have created a sixth mass extinction.

The late evolutionary biologist E.O. Wilson warned against the continuation of species loss and coined a different term for our epoch — the Eremocene, the age of loneliness. Laura Marris’ debut, “The Age of Loneliness,” is a series of nine meditations on this epoch, as framed by Wilson’s admonition. In her view, “Loneliness is worth listening to because it longs for reconnection — a hurt that illuminates its antidote, a symptom that desires its cure.”

The collection begins with “Lost Lake,” which positions readers to consider loneliness through both personal and ecological lenses. In the first sentence, Marris remembers asking her father, a birder, why a saltwater lake in Connecticut’s Westwoods would be called “lost” when the water could be seen. He tells her that settlers named it while surveying the area, not realizing that the lake was tied by a channel to a nearby marsh. Tidal ebb could cause the lake’s full retreat. When surveyors returned at low tide, they believed they’d lost the lake.

Diane passed away in December. Now I wander our home’s empty spaces at night like a character in a Gothic horror novel.

The lost lake sets us up for the quiet disappearances chronicled across the book. In some cases, these are natural phenomena or species or conditions that our society doesn’t know have been lost, and yet we’re lonelier for those untold vanishings. Marris writes: “I’m beginning to understand that absence itself could be a landmark. That sometimes, to know where you are, you have to navigate by what’s not there.” It’s the absence of her father, which comes up again and again, that produces the strongest sense of personal loss in the collection.

One of the book’s most beautiful qualities is its unusual mapping of interior landscapes as also ecological ones. The inner and outer are inextricably bound, she intimates; our actions shape what endures of the environment, but ecological absences shape our psyches and bodies, too. The land is in us. Marris builds on a quote from nature writer Robert MacFarlane: “We are part mineral beings too — our teeth are reefs, our bones are stones — and there is a geology of the body as well as of the land.”

“It’s easy to associate oil and stone with the primordial,” she elaborates on this thought, “but less easy to think, in our intimacy with roads, about the long time scales of the Earth. A verticality that travel can’t outrun.”

Young men, who tend to be more progressive than their elders, are the most isolated. Boys are retreating into the manosphere for reasons beyond addictive technologies.

A haunting reflection, “Extremotolerance,” starts with a discussion of rare species that thrive in extremes that could be fatal for others but moves on to an “extremotolerant” one: an eight-legged micro-animal, the tardigrade, or water bear, which lives in both moderate climes and harsh ones. Marris tells us a lunar lander carrying a library of data, DNA samples and dormant tardigrades in resin crashed on the moon and the load was flung onto the surface. The Arch Mission Foundation had sent the library to ensure our time isn’t forgotten by whoever comes after humans are gone; the organization aspired to make a backup of Earth. Marris likens the act to planting a flag, a colonial assertion. She asks if there’s anything humans can’t ruin but deepens the thought with “At the scale of an ice age, we wouldn’t really know what ruin meant.”

As with the essay on Lost Lake and later pieces, Marris folds in personal detail, which opens up the piece and makes it more intimate. She relates that her boyfriend, Matt, made a work of art titled “Tardigotchi,” consisting of an orb-like enclosure, home to a single tardigrade on one side, and on the other, an avatar to be fed. This allusion to the virtual Tamagotchi leads to scrutiny of other forms of technology, as Marris sketches connections between technology and automation and the Eremocene. Marris reminds us repeatedly: “Because it can be monetized and invested in, autonomy is loneliness’s neoliberal cousin.”

Self-driving cars and airplanes are part of this examination. “Safer Skies for All Who Fly,” for instance, looks at bird strikes, collisions between airborne birds and moving airplanes. “Cancerine” examines our valorization of the toughness of horseshoe crabs or “soldier crabs” in the face of human harvesting and a damaged ecosystem.

Opening a room in your home to someone is a generous act that can benefit hosts and guests alike.

A piece titled “The Echo” recounts the history of chemical dumping at Love Canal in Niagara Falls. Here, calling back to the Lost Lake image, Marris suggests that knowledge about the contamination of the groundwater has ebbed; it’s not clear whether toxic materials still lurk unseen. While at the park, she reluctantly disrupts a joyful moment when her friends discover cherries growing by revealing the information she has about the history. Hopefully, they ask Marris whether just a few cherries would be safe to eat. She’s unsure.

Epistemological uncertainty propels the final contemplation, “Shadow Country,” too. Marris describes losing the language for nature that her father taught her on their walks, and the resulting absence, and also what she didn’t know about him, such as whether he’d kept a list of the birds he’d seen. Her memories of him have become hazy with time’s passage, and this only underscores her interest in loss as a destabilizer of physical and psychological landscapes. Personal memories become their own kind of lost lakes. However, on balance, Marris takes the still-radical step of sidelining her personal history as only a sliver of a vast landscape of living things. Like poet and environmentalist Gary Snyder — except more comfortable with lament than adventuring — the author attempts to shed a manmade barrier between herself and the wild. At times, I longed for more energetic movements in Marris’ watercolor pieces — but hers is an undeniably profound elucidation of losses, some of which are tragedies we’ve occasioned with our hubris and aggressive industry, whether or not we’ve made a new geological epoch from that. Certainly, the author intends her delicate, sober tone. “For years, I wanted my thinking to be like a drop of oil falling in water — touch the surface and a skin of interlinked circles proliferates,” she writes.

Her approach counters the colonial, the destructive, the industrial. “The Age of Loneliness” holds up a reflection whereby we, too, grieve the sometimes invisible losses that we have been bequeathed.

Anita Felicelli is a novelist and critic who served on the board of the National Book Critics Circle from 2021-24.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.