Opinion: Abortion foes lost Round One on mifepristone. Here’s how their fight continues

The Supreme Court’s mifepristone decision on June 13 put a stop to one challenge to the drug used in more than half of all abortions in the United States. But antiabortion groups are already preparing their next line of attack.

New groups of plaintiffs might try to establish that they have standing where the doctors in the Food and Drug Administration vs. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine failed. But if Donald Trump wins the 2024 election, such lawsuits might be far less important to abortion foes: Conservatives already have detailed plans in place to use the executive branch to impose national limits on abortion.

The plaintiffs in FDA vs. Alliance made two sets of claims. First, they challenged the overall authority of the agency to approve and subsequently lift restrictions on mifepristone. The plaintiffs also argued that the FDA didn’t have the power to allow patients to receive the pills in the mail because the federal Comstock Act, a 19th century obscenity law, includes a ban on mailing and receiving abortion-related items.

We should be thankful that the ultraconservative Supreme Court unanimously dismissed an antiabortion case that never should have gotten that far in the first place.

In holding that the Alliance plaintiffs didn’t have standing to sue, the Supreme Court didn’t say a word about the merits of either of those claims. So it’s no surprise that other plaintiffs might try to bring them again before the justices. The leading contenders are the states of Kansas, Missouri and Idaho, which had sought to intervene in the case, a request turned away by the Supreme Court.

The states’ attorneys general have suggested that they will continue the litigation, with a new argument on standing. A preview of that claim came in the states’ petition to intervene: They argued that because their citizens could get mifepristone from doctors out of state, the states’ own interests were affected. Medicaid recipients who suffered mifepristone complications were imposing costs on state medical systems, they added, and the availability of mifepristone was making it difficult to make and enforce abortion bans.

There may be problems with the states’ case for standing too. Patients might experience complications if they take mifepristone, which might impose costs on the states. That doesn’t sound so different from the weak hypotheticals on which the Alliance plaintiffs relied. And what about Missouri and Idaho’s supposed sovereign interest in enforcing their abortion bans when other states allow it? The answer the court gave the Alliance doctors would seem to apply: “A plaintiff’s desire to make a drug less available for others does not establish standing to sue.”

Mifepristone has been used more than 5 million times in the U.S. since its FDA approval in 2000. The Supreme Court will weigh a challenge to expanding its access.

Kansas’ case for standing is even more puzzling. Abortion is legal in Kansas until 22 weeks, albeit with restrictions. Barely more than a month after Roe was overturned, Kansans expressly voted against amending their state constitution to say there was no right to abortion. How will the state make the case that it is harmed by the approval of mifepristone when its own voters chose to preserve abortion access?

Whatever the fate of the case the Alliance doctors started, abortion foes and conservatives understand that the war against mifepristone and medication abortion can’t just depend on litigation. For example, Louisiana recently passed a law categorizing mifepristone and misoprostol, another drug used in medication abortion, as controlled substances, making it easier for the state to surveil patients, doctors and pharmacies and to punish anyone in possession of the drugs without a prescription. Idaho passed a so-called trafficking law that criminalizes those who help minors travel out of state or obtain abortion pills without parental consent.

Despite the Supreme Court’s ruling protecting access to a common drug used in abortions, the far right will continue its assault on women.

But even these kinds of strategies may be far less important if Donald Trump wins a second term. The Heritage Foundation and a coalition of more than 100 conservative groups have laid out a detailed plan — known as Project 2025 — for a second Trump administration. The plan begins with a call for the FDA to “reverse its approval of chemical abortion drugs,” including mifepristone, or at a minimum, to eliminate the telehealth option for the drug.

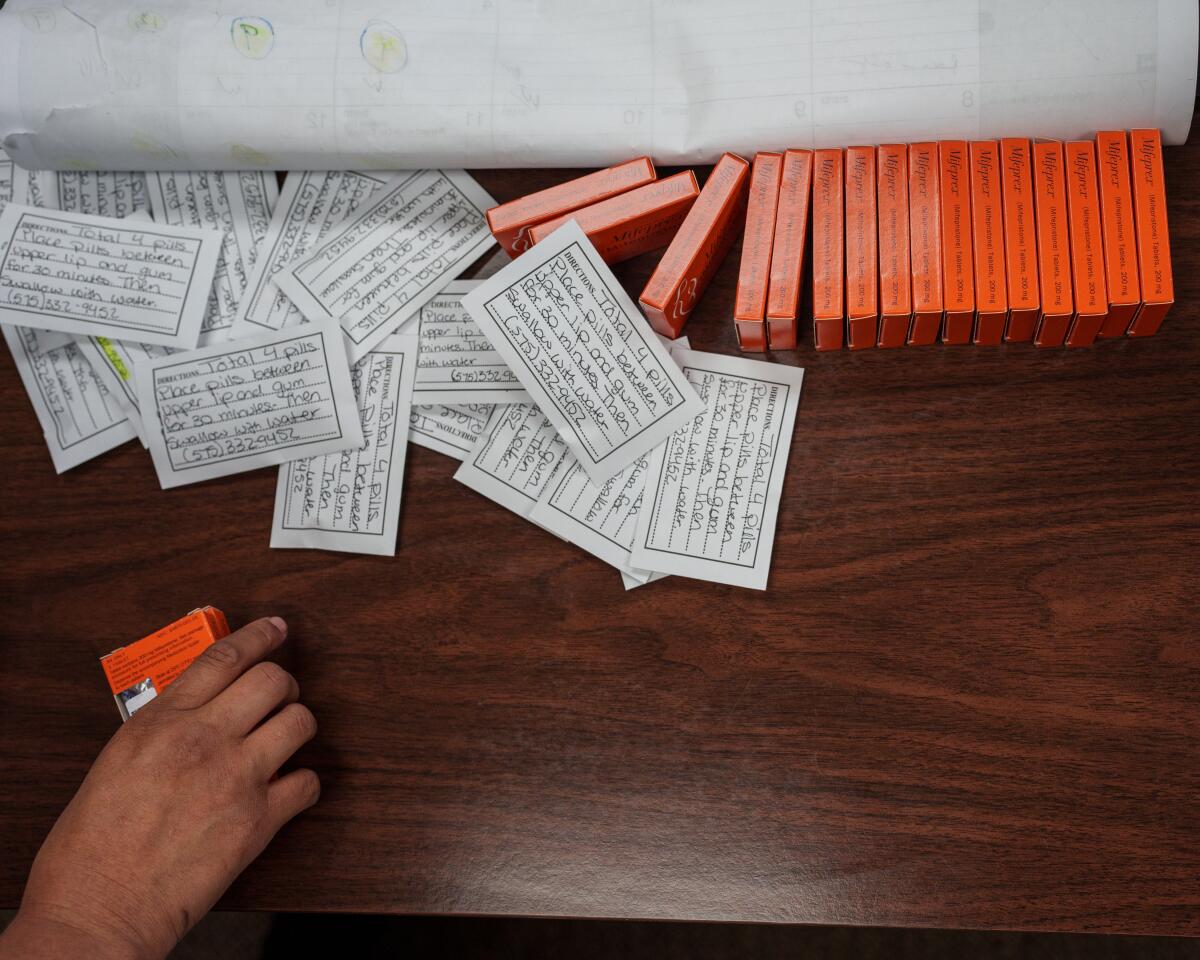

Thousands of abortions can take place each month in states that ban the procedure because the telehealth option allows patients to get a prescription and get the pills by mail. With a Trump appointee as secretary of Health and Human Services, and one heading the FDA , the government might approach mifepristone differently without the pressure of a lawsuit. Some legal scholars argue that structural features of the federal Food and Drug Act could even allow the HHS secretary alone to override scientists at the FDA.

As the Supreme Court weighs limiting access to mifepristone, here are some of the numbers on abortion pill usage in the U.S. and California.

Then there is the ancient Comstock Act — moribund but still on the books. Gene Hamilton, a prominent figure in the first Trump administration, argues in the Project 2025 plan that the Department of Justice could simply dust off the 151-year-old law and start criminally prosecuting the mailing or receipt of mifepristone. If the Supreme Court buys this interpretation of the Comstock Act, despite its flaws, such an executive action would get around the thorny questions about standing raised in Alliance.

The Supreme Court deflected the Alliance case against mifepristone. We may well see it reappear in some form on the court’s docket next year. But whatever shape Alliance 2.0 takes, in the fight over a national abortion ban, it’s unlikely to be the main event.

Mary Ziegler is a law professor at UC Davis and the author of “Roe: The History of a National Obsession.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.