Opinion: The immigration system can bend toward justice. One Orange County man’s case shows how

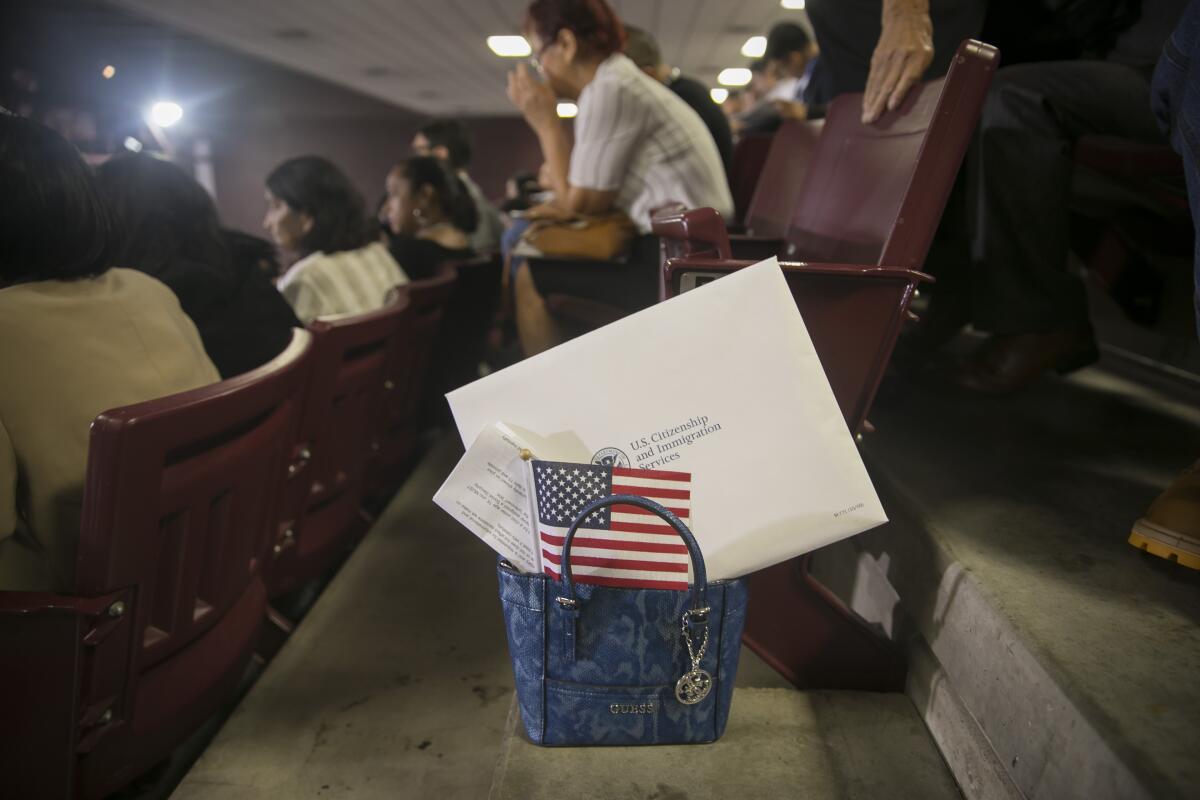

On a sunny January morning, in the windowless office of a nondescript government building, Jose Franco Gonzalez was sworn in as a United States citizen. There is not a lot of good news in immigration these days, with President Biden doubling down on proposals that would gut remaining asylum protections and former President Trump threatening mass deportations. But Franco’s story is a reminder that a better immigration system remains possible. His experience points toward a path for getting there.

Fourteen years ago, I met Franco in another windowless room. That room, less than a mile from where he would one day naturalize, was in an immigration jail. At the time, Franco had been imprisoned for nearly four and a half years after a judge found him incompetent to move forward in removal proceedings. I was a young lawyer providing free legal orientations at the jail. But Franco couldn’t sign up to attend; he couldn’t write his name. Instead, an immigration officer alerted me to his case.

At our first meeting, Franco’s skin was pale, nearly translucent, from years behind bars. He was almost nonverbal. Although 29 years old, because of a lifelong intellectual disability, he had the mental capacity of a young child, by some measures as young as 2 years old. We sat for nearly an hour together that day. I tried to draw out what information I could about his story: The arrest that landed him there? A rock thrown in a neighborhood fight led to a criminal sentence, after which federal authorities took him to an immigration jail. Who was his family? A tight clan of his parents and 12 siblings, most of whom were permanent residents and U.S. citizens. What was his legal status? He did not yet have papers, although his brother had filed a petition on his behalf years before. What was it that he hoped for? To get out and eat carnitas.

At the time, Franco was among hundreds, if not thousands, of people with serious mental disabilities detained in immigration custody, according to a report released by Human Rights Watch and the ACLU. Yet immigration authorities had no system for identifying people with such disabilities, and immigration courts had no process for providing them legal representation. Unlike in criminal cases, in which defendants have a right to an attorney, most people are forced to represent themselves in immigration courts against a trained government attorney.

Most individuals in Franco’s position were pushed through the system and deported without any recognition of their unique needs. In his case, an immigration judge recognized she couldn’t provide a fair hearing because of his disability. But instead of appointing him counsel or ordering his release, she simply closed his case and sent him back to his jail cell, where he sat — without seeing a judge — for four and a half years. Franco’s immigration incarceration lasted nearly five times the length of his criminal sentence, cost more than $250,000 in taxpayer money, and wreaked immeasurable harm on a man who could not recall his birthday, much less understand what had happened to him.

After I met with Franco and his family, who desperately wanted him home, immigration authorities still refused to release him. Instead, they restarted his removal proceedings. We sued. That lawsuit, filed in March 2010, led to Franco’s immediate release. He has since thrived — living with his family again in Orange County and participating daily in a community-based program that helps adults with developmental disabilities learn vocational and social skills.

The suit also eventually led to a groundbreaking decision that established a right to legal representation for immigrants with serious mental disabilities in immigration custody who are found incompetent to represent themselves. Although the court’s 2013 decision applied only in California, Washington and Arizona, in its wake the federal government rolled out a nationwide legal representation program. To date, more than 2,500 people throughout the country have received counsel through the National Qualified Representative Program.

As a new generation of advocates emerges, I am always startled to find how many begin their careers as self-described “Franco attorneys.” Indeed, among the few bright spots of the Senate border security bill that failed in February was a provision that would codify in the immigration statute the right to appointed counsel for those deemed incompetent (albeit with many of the Franco court’s protections watered down).

No system is perfect, and this one is no exception. There remain significant gaps in screening and identification, competency assessments are often done by judges without the aid of professional mental health evaluations, and people still languish in immigration custody for months or longer as their cases wind through the system. And, to our collective shame, the right to legal representation has not been extended to any other groups in immigration proceedings, including children. Still, there is no question that Franco’s namesake litigation not only changed the course of his own life, but also created a sea change in an immigration system that often feels impossible to move toward justice.

The next positive changes may be harder to win in the courtroom, and almost certainly won’t come from the halls of this Congress. But the Biden administration has the power to make good on its promise of a more humane immigration system, including by extending the National Qualified Representative Program to other groups, among them children and families. No court order or act of Congress is required to do so, just political will. And, of course, dollars: Diverting from the nearly $3 billion spent annually on immigration detention is a good place to start.

States and localities can also play a crucial role in expanding legal representation as well as other protections in the face of federal gridlock. And immigrant organizing, especially among youth, will continue to break open new paths for change. As we head into another election cycle in which the demonization of immigrants and the failures of our current system take center stage, Franco — now a U.S. citizen — is living proof that a better immigration system is possible.

Talia Inlender is deputy director of the Center for Immigration Law and Policy at UCLA School of Law.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.