In Jane Smiley’s rock ’n’ roll novel, does good sense make good fiction?

Book Review

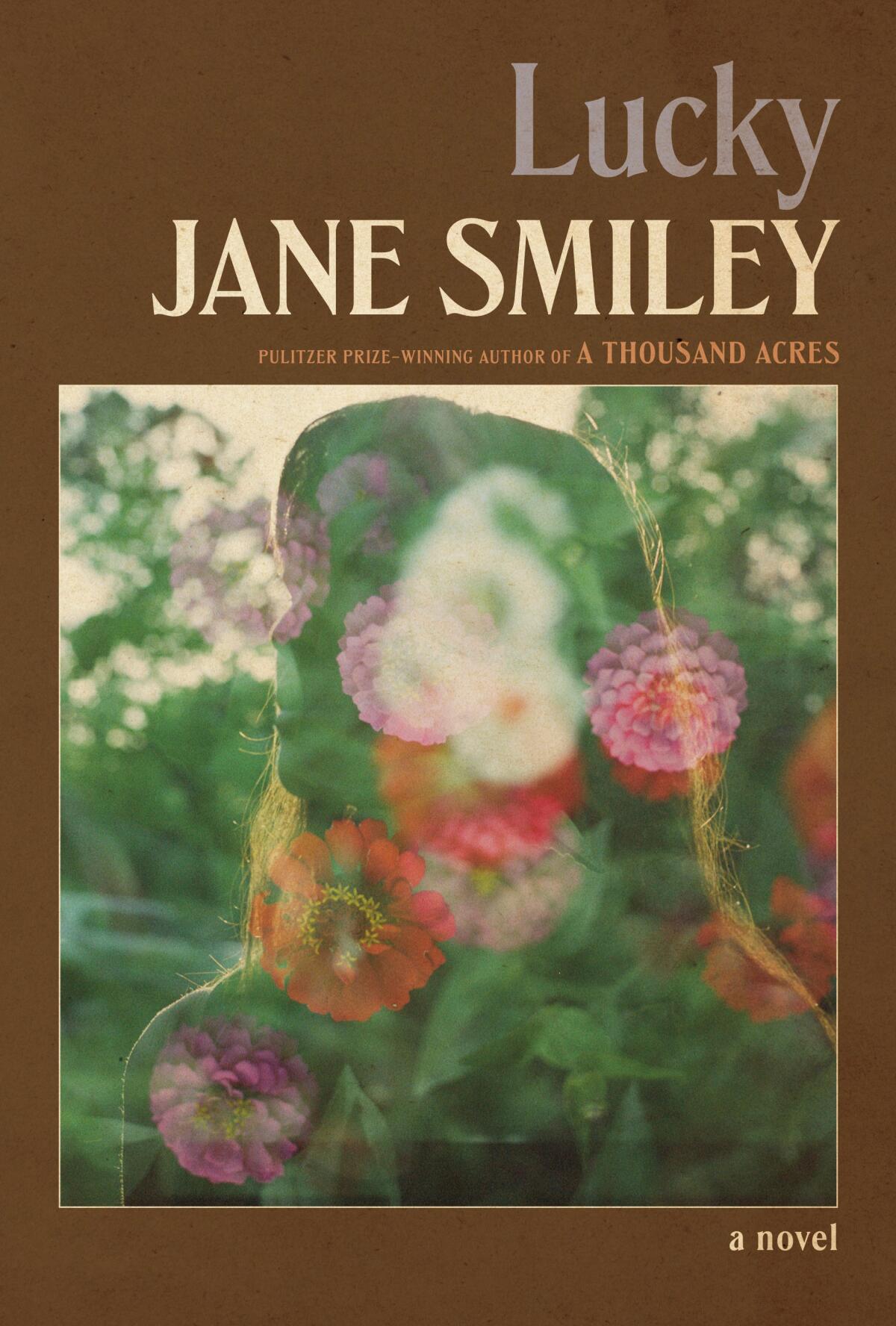

Lucky

By Jane Smiley

Knopf: 384 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Toward the end of Jane Smiley’s new novel, “Lucky,” its narrator takes a moment to flip through her mother’s record collection. It’s got a lot of ’60s folk-rock, including, she notes, “the four J’s.” Presumably she means artists like Joni Mitchell, Joan Baez, Judy Collins and Janis Ian. But maybe one of the J’s is the narrator herself — Jodie Rattler, a moderately famous singer with a knack for writing melancholy love songs.

“Lucky” is framed as a rock ’n’ roll novel, but it’s a tricky and surprising one. Smiley seems determined to upend the conventions of the genre. Rather than a tale of outsize fame and fortune — or vice-induced failure — the Jodie Rattler story is about how she … does OK, rising from backup singer to ’60s and ’70s solo act who enjoyed modest success. She rode the folk-rock boom to hit the lower range of the Billboard charts at a time when that still meant decent money. (She logs her singles’ earnings down to the penny: One got her $65,857.52.)

And rather than play coy about lyrics, as many rock-novelists do, Smiley takes a crack at writing a bunch of them, which have a few groaners but are more often creditable faux-Joni: “I’m done with men, or so I say / Women say that every day / But we want something / Something fine. And you are It, / Though you’re not mine.”

But the biggest distinction between “Lucky” and other such novels is that music doesn’t define its hero. “Lucky” is as much a story about Jodie’s experience racking up lovers (23, she counts) and dedicating time to her family back in her hometown of St. Louis. Music gives her a measure of fame, but she can take it or leave it.

The same goes for men: Though she falls for a kind-hearted Englishman named Martin (pointedly, the name of a bespoke guitar brand), she’s comfortable abandoning him. Visiting his parents at their tony manor, she sees married domesticity as something cold and alien. Becoming a person in full, for her, means avoiding conventional attachments: “I still sometimes felt a longing for his grace and the comfort of his embraces, but I didn’t feel guilty for setting out on my own,” she muses.

Jodie’s sensibility is, well, sensible. Throughout her life she’s determined to preserve the good luck that provides the book with its title. But Jodie’s story opens up the question of whether good sense makes for a good novel.

The 44th annual awards will recognize outstanding literary achievements in 13 categories, including the new prize for achievement in audiobook production, with winners to be announced on April 19

Domestic fiction tends to thrive on strife and fireworks — something Smiley knows well herself, having won the Pulitzer for 1991’s “A Thousand Acres,” a Midwestern farm saga modeled after “King Lear.” There’s some of that conflict in “Lucky,” as Jodie returns home to find her mother sinking into alcoholism. (“At what point do you say to your mother that she looks like a war orphan?”) But Smiley eschews the screamfests and betrayals.

What emerges instead in “Lucky” is a simple yet provocative idea — what if a woman protagonist were allowed to live independently on her own terms, not tied down by typically novelistic men or the bad blood that infects family life? (Whatever the opposite of a Joyce Carol Oates novel is, this is it.) A Jodie lyric gets at the idea: “Nobody told me the pleasures of fading, / That success requires evading.” The novel’s title, upbeat on the surface, is darkened by the notion of how rare such a character is. And the novel’s tension isn’t about Jodie seeking freedom so much as figuring out how to live as a person who’s always had it. Late in life she writes a “regrets song…about spending my whole life being careful. What had I missed?”

To that end, Jodie writes about her process of trying not to miss things, to be alert to myriad ways she’s connected to music and the world, albeit cautiously. (She seeks out her absent father and stands next to him in a New York deli line, just because.) She strives to be a good observer of both life and herself, and to put it into words. There’s a name for that: songwriter. There’s another name for that: novelist.

In ‘American Spirits,’ the late author Russell Banks returns to rural New York to explore the ego, territorialism and violence that define our society.

The cleverest trick in “Lucky” is that it introduces a fifth J: Jane Smiley, who we first meet as an unnamed high-school classmate of Jodie’s, a “gawky girl” who grew up to write acclaimed novels. Smiley isn’t Jodie, exactly, but Smiley is chasing the autofictional vibe of Rachel Cusk and Karl Ove Knausgaard, trying to capture the grit of everyday life, just like a songwriter might.

“Lucky,” much like Smiley’s epic the Last Hundred Years trilogy, operates at a deliberately low boil. Life and death flow in and out, and Smiley observes it clearly but empathetically. (Not for nothing is Dickens among her favorite writers.) And “Lucky,” like those books, shows how the business of just being yourself can be a source of struggle and effort. She is, Jodie writes, a “thoughtful young woman with ideas and determination,” and impressively that is enough to carry the novel.

There’s no signal that “Lucky” is Smiley’s final book, but if it were, it would make for an admirable summing up — the story of a well-traveled, keen-eyed writer who’s spent decades making sense of the world in words, and taking pleasure in it for its own sake. A lucky way to make a living.

Mark Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.