Editorial: Board of Supervisors’ silent sign-off on $25-million payout fails accountability test

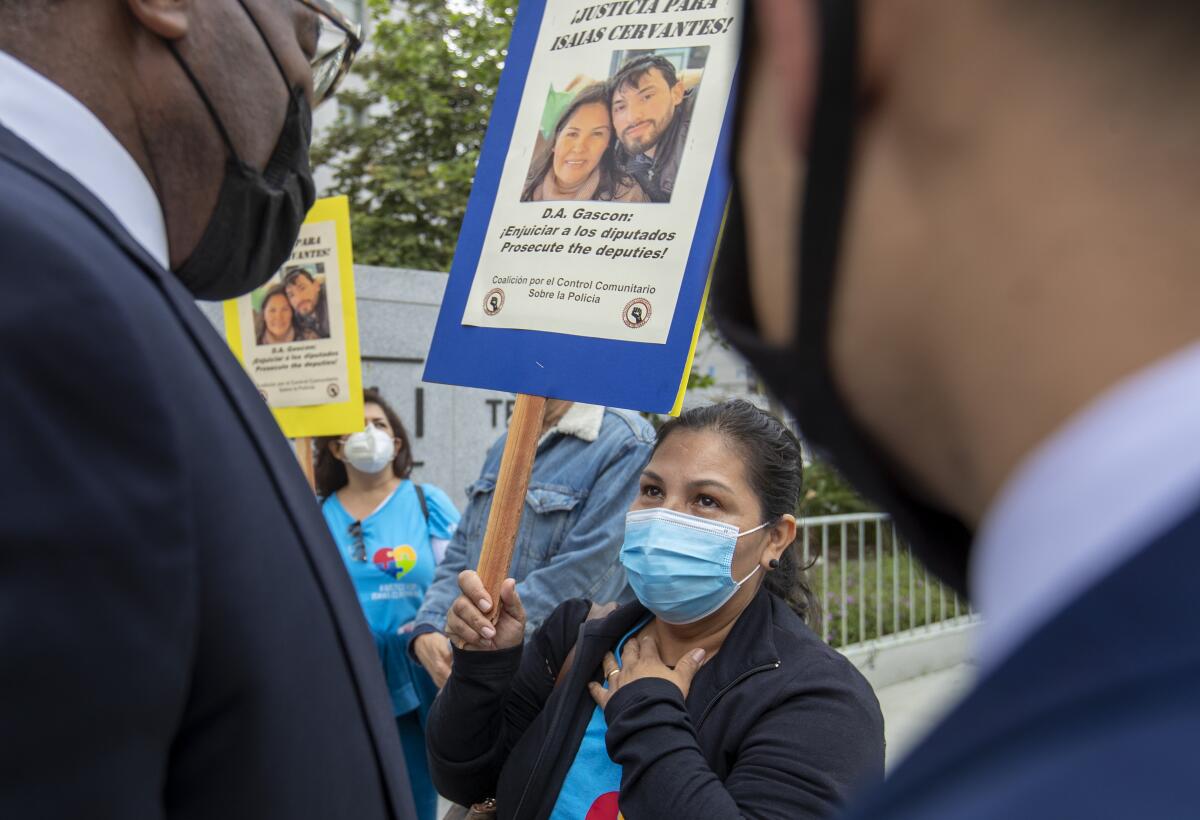

The Board of Supervisors is the guardian of Los Angeles County’s budget and has oversight over county policies and actions. So it is disappointing, to say the least, that the supervisors asked no questions and engaged in no discussion last week when they signed off on a $25-million settlement for Isaias Cervantes, a Cudahy man who was shot in his home by sheriff’s deputies on March 31, 2021.

They were responding to a 911 call by Cervantes’ sister, who advised the dispatcher of her brother’s disabilities and said he had become aggressive with their mother. She asked if deputies could take him to the hospital.

Deputies’ shooting of Isaias Cervantes in his own home will probably cost Los Angeles County $25 million without spurring a change in training or tactics to prevent something similar from happening again.

When the two deputies arrived, Cervantes was seated inside on a couch. He declined to go outside to speak to the deputies but invited them in. They entered and told him he was not under arrest but they would have to handcuff him. When he resisted, they scuffled, and one deputy said Cervantes tried to grab his gun. The other deputy shot him.

It’s not that county taxpayers should begrudge the payment to Cervantes. He was paralyzed in the incident, exacerbating existing conditions that include deafness and autism.

The recommendation last week, which described a historically “flawed” bureau, spurred new tensions between the sheriff and the inspector general.

But in approving the settlement, the board in effect signed off on the Sheriff’s Department Summary Corrective Action report that includes no real corrective action, apart from admonitions to sheriff’s personnel to follow existing policy by including senior personnel and a Mental Evaluation Team when responding to calls to assist people experiencing a mental health crisis.

Corrective action reports are integral to county legal settlements. They are supposed to lay out what went wrong in an incident and why, and how policies and procedures or discipline will change to ensure that something similar does not happen again. Legal settlements are costly, but ideally they lead to improvements and efficiencies that save money and produce better service.

Isaias Cervantes, a deaf and autistic man shot and paralyzed by sheriff’s deputies in his own home last year, has been traumatized by public agencies that are supposed to help him.

That didn’t happen with the Cervantes report. And the settlement sends a message to the public that, even though the county will pay a stunning amount of money, no one did anything wrong, no procedures need to change and no one will be held accountable. And if the same thing happens again, the county will likely pay all over again.

The payout comes in the wake of a February report from county Inspector General Max Huntsman that sharply criticizes the sheriff’s Risk Management Bureau, which prepares the department’s corrective action reports — and also helps defend against lawsuits.

L.A. County will pay $700,000 to a public radio journalist who was slammed to the ground and arrested by deputies while covering a 2020 protest.

There may be an inherent conflict between those two tasks, as Huntsman believes. Building a legal defense requires selecting and presenting facts that suggest the Sheriff’s Department and its personnel did nothing wrong, and that its policies and procedures are in no need of fixing. Identifying failures, in order to prevent recurrence, requires the opposite — critical examination of policies and actions.

The conflict is so great, the inspector general said, that the sheriff’s Risk Management Bureau should be dissolved.

Sheriff misconduct often results in huge payouts to injured parties, but it’s the public that pays, leaving law enforcement agencies little incentive to improve. They will become accountable only when they start picking up the tab for the damage they cause.

Sheriff Robert Luna pushed back on Huntsman’s report, calling his criticism “gratuitous attacks” on the department. Luna correctly noted that it is common for law enforcement agencies to combine risk management and legal defense. But it doesn’t mean the arrangement is healthy.

Separately, the Office of County Counsel wrote that it does not rely on the sheriff’s Risk Management Bureau to formulate litigation strategy. Still, it said, the bureau is needed to gather documents and witnesses.

County legal liability is not limited to the Sheriff’s Department, although it is typically responsible for more than half the money paid out in any given year. Last year, the county paid $257 million in judgments and settlements.

So how will this fundamental dispute over county legal defense and huge payouts be resolved, and in what forum will it be discussed?

The women were ordered to line up outdoors, strip, and toss their clothes onto the concrete in front of them.

The Board of Supervisors created a Civilian Oversight Commission to investigate problems within the Sheriff’s Department, and the commission would be an appropriate place to begin the conversation. But in the end it is the supervisors who are accountable for county policy, county wrongdoing and county spending.

Their swift approval of the Cervantes settlement came 7 hours and 23 minutes into their April 9 meeting, so they are accustomed to spending time discussing at least some issues. They should also discuss the adequacy of corrective action reports, especially those that fail to explain huge settlements such as the one in the Cervantes case.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.