In the 1960s, the Peace Corps ran an ad on TV and in countless magazines that showed a tumbler partially filled with water. Did you see the glass as half empty or half full? If you answered half full, the small print and the voice-over said, you were suited to the Peace Corps — that is, you viewed the world through a lens of hope rather than despair.

In this season of Easter, which Christians read as triumph over despair and death, we need to affirm the importance of hope, to find that half-full perspective.

In his first letter to the Corinthians, St. Paul identified what have come to be regarded as the three theological virtues: faith, hope and love. Hope is the one that, over the centuries, has attracted the least attention.

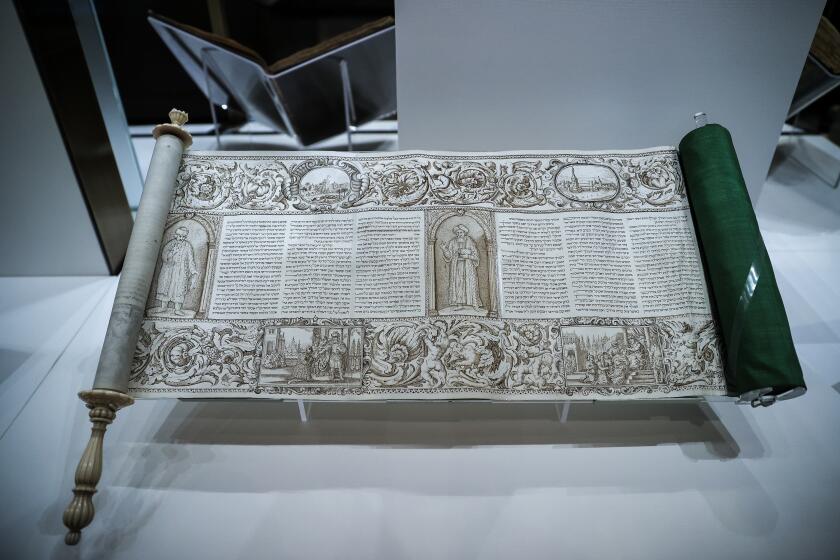

The Book of Esther and the Haggadah tell of Jewish victories and the punishment of Jewish enemies. In 2024, they are prescient, agonizing and troubling as never before.

Faith — as in the impossibility of belief, the beauty of it or the simplicity of it — has received its due and more. And love (the greatest of the three virtues in St. Paul’s formulation), agape and eros, has been pondered and analyzed endlessly on greeting cards and in philosophical treatises, great literature and treacly rom-coms.

But what about hope?

If faith is a disposition of the spirit, and love is a disposition of the heart, hope is a disposition of the will. The workings of both faith and love are, to some degree, outside our ken, beyond our rational control. Hope, on the other hand, is volitional.

We can choose to be hopeful, even if faith is elusive and love distant.

Right now, making that choice isn’t easy.

The annual Palm Sunday celebration comes as the Israel-Hamas war rages on in Gaza. But the conflict has little effect on the procession.

What’s easy is to be overwhelmed by despair, by hopelessness. Lord knows we have ample reasons: the ravages of climate change, the persistence of poverty, senseless death and destruction in Ukraine and the Mideast, the looming possibility of a second amoral administration headed by a pathological narcissist.

We worry about the high price of groceries, the obstinacy of racial disparities, the inertia of Congress, the self-dealing of Supreme Court justices, the proliferation of loopy conspiracy theories and the credulity of too many Americans. These are legitimate concerns, and the glass looks half empty.

On the other hand, wages and employment have risen. The United States remains an economic powerhouse and generally a force for good in the world. In January 2021, we withstood our most severe constitutional crisis since the Civil War. The wheels of justice turn slowly and sometimes a bit out of balance, but our democracy, imperfect as it is, so far has proven remarkably durable. The glass is half full.

There are reasons for hope, even though we must remain vigilant.

You don’t have to share the Christian belief in Bible stories to understand their message that hoping against hope and defying evil is humanity’s task. In the Hebrew Bible, Abraham and Sarah, both in their 90s or beyond, learn that they are about to have a child. In the New Testament, the blind man sees and the lame man kicks aside his crutches. Lazarus is coaxed out of his tomb even though his body had begun to stink. And Jesus, crucified, rises from the grave.

Easter summons us to hope, even when hope is counterintuitive, countercultural. We can will ourselves to see the glass half full. These days, to hope is both an act of volition and a gesture of defiance.

Randall Balmer, an Episcopal priest, teaches at Dartmouth College and is the author of “Passion Plays: How Religion Shaped Sports in North America.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.