Editorial: On medication abortion, the Supreme Court may actually do the right thing

It always seemed farfetched that anti-abortion doctors could argue that they have the right to ask a court to severely restrict a drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration simply because they don’t want to treat women who might experience complications.

Do they even have standing to bring this case? Do they have any proof they have been so harmed or injured that it justifies restricting FDA-approved access to mifepristone, the first in a two-drug regimen for medication abortion?

An Alabama court decision brought national attention to the creeping personhood movement that seeks to extend legal protection to fetuses and embryos.

These are among the questions raised when the Supreme Court heard oral arguments Tuesday in a case from Texas by the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, an anti-abortion group that claims the FDA did not adequately study mifepristone before putting it on the market in 2000.

Last year, U.S. District Court Judge Matthew J. Kacsmaryk — a staunch opponent of abortion — ruled in favor of the alliance, which wants the drug pulled from the market. The Biden administration appealed to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, which allowed doctors to continue to prescribe mifepristone, with the caveat that the medication be used as it was approved in 2000. The FDA lifted various rules and restrictions on its use in 2016 and 2021. (The Supreme Court put the court’s changes on hold while the case moves through the appeals process.)

It is a relief that the justices seemed skeptical that a group of doctors who don’t prescribe abortion medication has the legal right to lodge a complaint against an approved drug that has been safely used for more than two decades. (Serious complications occur in less than a third of 1% of uses.) They spent most of their time asking questions about standing and much less about whether mifepristone would be safer with more restrictions.

Even in states where abortion access is not under threat, purple districts could turn blue because the right is so out of step with American voters.

This suggests that the justices may end up siding with the FDA when handing down the ruling, possibly in a few months. If they were to rule against the FDA, it would be a nightmare, enacting sweeping restrictions on the most common form of abortion in the country.

Last year, 63% of the 1 million abortions performed in clinic settings in the U.S. were provided through medication. Even California and other states with robust abortion protections would see access to medication abortion restricted.

For example, if the Supreme Court decides medication abortion should be available only under regulations in effect before 2016, that will end the practice of getting prescriptions through telehealth appointments and the mail. It could shorten the window in which pregnant women can get prescriptions and increase the number of required in-person doctor visits. Overall, the burden of more restrictions would fall hardest on people who have the most difficult time getting access to any method of abortion.

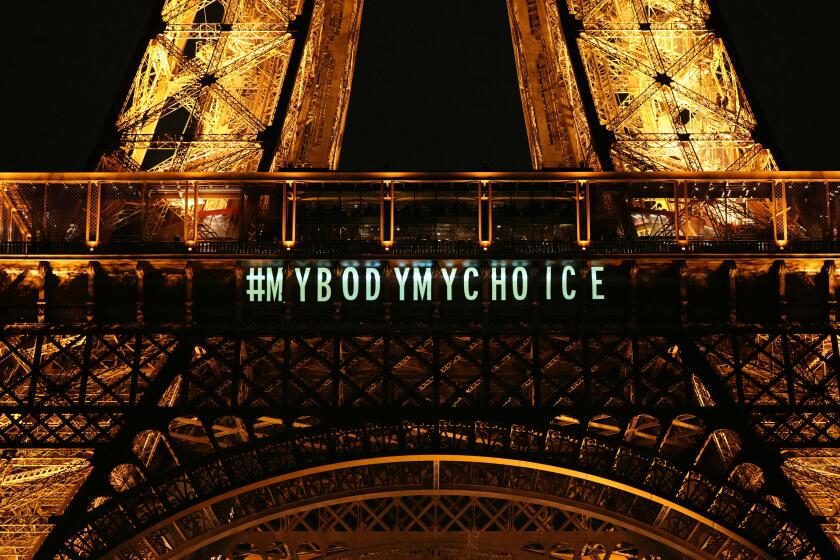

Fearing that a future government could do what the U.S. Supreme Court did — reverse the right to abortion — France champions women’s rights.

A ruling in favor of the plaintiffs could open the way for challenges to FDA approval for other pharmaceuticals and could perhaps have a chilling effect on the development of new drugs.

Justice Neil M. Gorsuch asked Tuesday if the plaintiff doctors’ remedy for their injuries — rolling back restrictions on the drugs — was going way beyond what was necessary.

“We say over and over again: Provide a remedy sufficient to address the plaintiff’s asserted injuries, and go no further,” he said. But this case “seems like a prime example of turning what could be a small lawsuit into a nationwide legislative assembly on ... an FDA rule or any other federal government action.”

We agree that it would be the wrong course to take for a drug that’s statistically safer than Tylenol, which is available over the counter. So it’s encouraging to hear skepticism from a justice who voted with the conservative majority when the Supreme Court overturned Roe vs. Wade in 2022, returning the matter of abortion to state legislatures.

Perhaps the most ominous moment came when Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. asked whether the FDA should have considered the Comstock Act before allowing the drugs to be mailed. That moribund relic of a morals law from the 19th century says nothing having to do with abortion can be sent through the mail. But the Justice Department has already said it’s legal in most cases to mail drugs that can be used to perform abortions. The court should leave the Comstock Act out of its deliberations.

Even for a court that has been opposed to abortion, the decision here should be straightforward and obvious. This case was never about abortion laws. It’s about the FDA’s authority to make decisions. Judges should not be weighing in on how to prescribe any drugs, including those used for abortions.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.