Opinion: Social media can be toxic for women. Here’s how to change that

On social media, most of us don’t think too hard about what we’re doing as we “like,” scroll and swipe across our screens. But I study how Americans engage with these platforms. In researching my new book, I spoke to women and girls across the country about how social media is affecting their lives. What I learned isn’t pretty. Still, we can improve women’s lives online — by radically rethinking whom we follow, what we share and what we do when we witness abuse online.

One woman whom I interviewed, who asked to be called Vivian, told me she developed an eating disorder as a teenager after she fell down a rabbit hole on Instagram, consuming toxic “fitspiration” (fitness inspiration) content. Now in her 20s, she works as a personal trainer and has realized that the so-called “Instagram body” (you know it: flat belly, big hips) usually requires surgery. But her clients keep pulling up pictures of influencers and saying they want to look like these people.

In recent years we’ve seen a rise in body acceptance and fat inclusivity, but thinness has remained a goal for women.

Social media isn’t just giving women unrealistic standards for themselves. It’s also inviting the world to judge women more than ever before. Now when a picture of a woman is posted online — whether she’s in the public eye or not — social networks provide a forum for people to weigh in with (often vicious) comments about her appearance and, let’s not forget, whether she’s authentic or “fake.” Cornell professor Brooke Erin Duffy has shown how the so-called “authenticity policing” of people by dissecting their appearances and behavior is a practice typically reserved for women.

Social networks are also having a dramatic effect on how women are treated offline. Dating apps, for example, give the impression that there’s always more people to swipe on. When people think they have options, they value their romantic partners less. This can help explain why the women I interviewed kept complaining that the men they matched with treated them terribly.

Not surprisingly, these men are not fond of the treatment they feel so comfortable weaponizing against others.

That’s when their matches turned out to be real people. Women told me they were regularly catfished online. This is when a scammer typically makes up a fake identity, establishes an emotional relationship with someone on an app, and then asks the targeted person for something like cash to fly to see them or help them invest their money (before disappearing with it). Cybercriminals see women who are dating as vulnerable because of the popular stereotypes of women as emotionally needy and desperate for relationships.

On social media, mothers are also particularly targeted with misinformation designed to exploit our vulnerabilities. Savvy predators know that moms of severely autistic kids who find it difficult to leave the house, for example, are often isolated, desperate for help and looking online. That makes them good targets to purchase quack essential-oil “cures” (at premium prices, of course). And women and girls also come up against the mother lode of misogyny and hate online, from rape threats to “jokes” about violently abusing women that have become a common part of youth culture online.

Opinion: How the Supreme Court should rule on Texas and Florida laws against social media moderation

The cases, NetChoice vs. Paxton and Moody vs. NetChoice, concern Florida and Texas laws prohibiting moderation by platforms such as Facebook and YouTube.

People often ask me why women should use social media at all if it’s this harmful. The reason is that these platforms are also places where we can empower ourselves — whether promoting our work, weighing in on issues we care about or nurturing relationships with friends who support us.

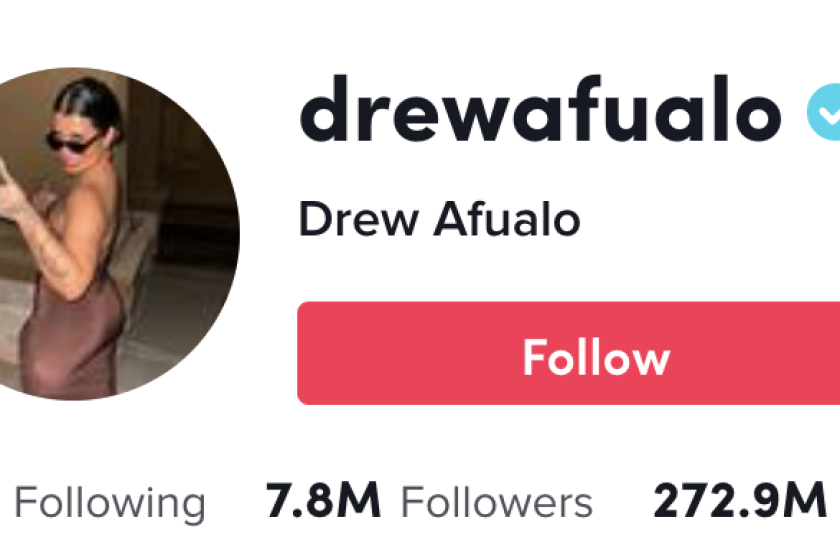

But it’s not simple. When women use social networks to bolster our careers, we often end up with fewer followers, reposts and resulting opportunities than the men in our fields. Part of the problem is that men are still the ones people turn to for expertise.

Without social media to occupy me at all times, my mind went empty: gloriously empty, with space for nature and new ideas. It was exhilarating.

It’s on all of us to recognize this implicit bias and follow and amplify the posts of more women. Start by following 10 more women. If you’re looking for experts on a particular topic, SheSource, a database maintained by the Women’s Media Center, offers excellent lists of women who tend to be active on social media. On my own website, I’ve also posted a list of “feminists to follow” to get you started.

We also have to change what we do when we witness sexism and misogyny online. It’s generally not a good idea to fire back at trolls, as engaging with content sends a signal to algorithms that people want to see more of it. But it is a good idea to have offline conversations with people you know when you see them post content that is degrading or dismissive of women. Tell them why they’re wrong.

Also, many women don’t want their abuse given more attention with things such as defensive comments. But a good way to respond, if you see a woman attacked online, is by posting positive things about her such as compliments on something she did in her career on LinkedIn that might be seen by hiring managers, or posts about things she has written or produced on social networks like X and Instagram to help promote her work.

We should also report content we see that violates the community standards of platforms directly to the platforms. While tech companies are notorious for not responding to these reports or telling women that the rape threat they received didn’t violate the rules, it’s still a way of registering our discontent; and if more of us did this, the companies might pay attention.

Finally, we should rethink what we share on social media. Instead of the latest memes, post about issues that affect your life — and give other women likes and reposts when they do so as well. If we all did this, we could radically change social networks to be places that empower women.

Kara Alaimo is associate professor of communication at Fairleigh Dickinson University, where she created the university’s academic programs in social media. She is the author of “Over the Influence: Why Social Media Is Toxic for Women and Girls — and How We Can Take It Back.” @karaalaimo

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.