A poet’s novel of utopia shows less an ideal than, perhaps, a road map

Book Review

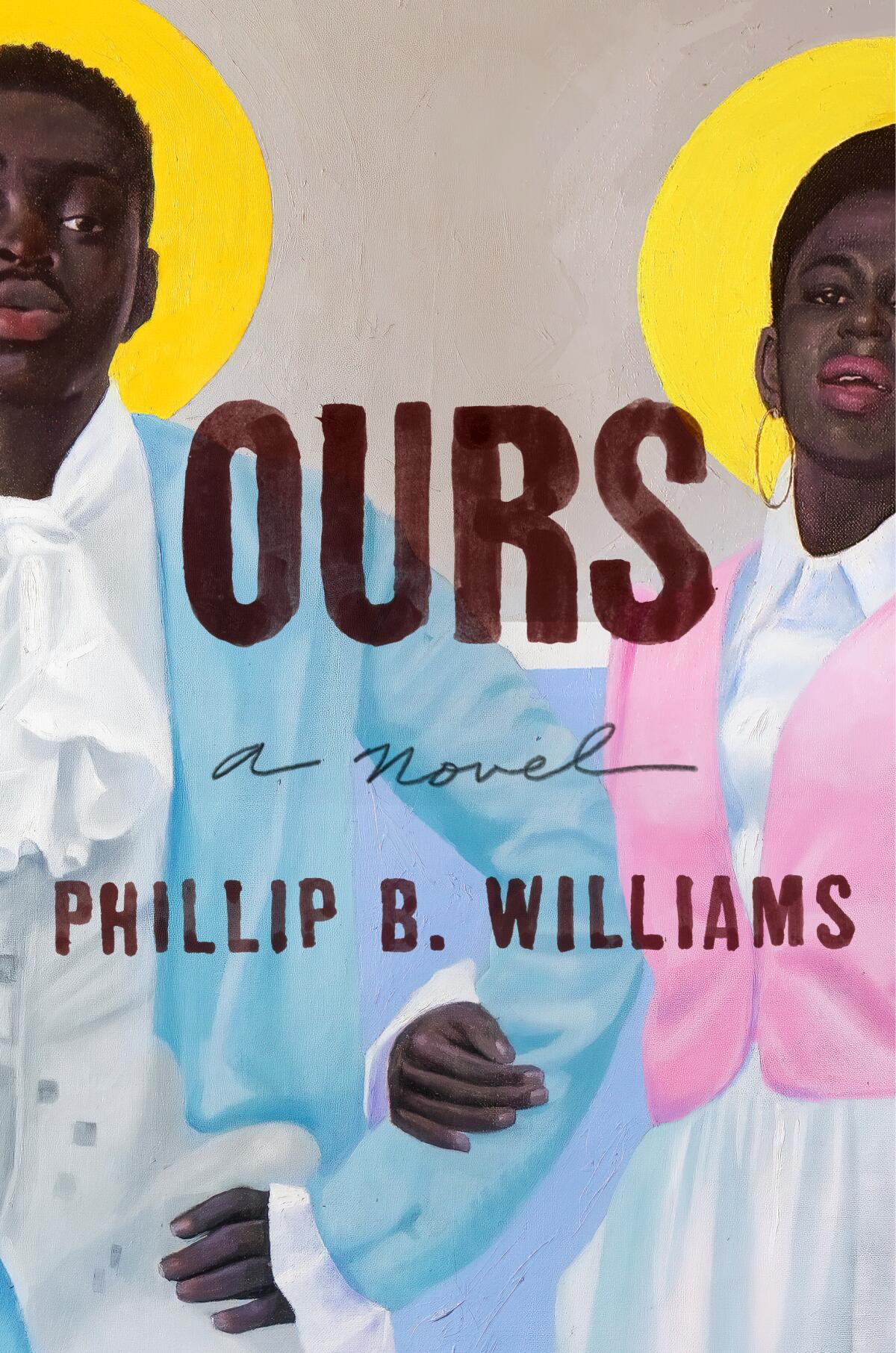

Ours

By Phillip B. Williams

Viking: 592 pages, $32

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Award-winning poet Phillip B. Williams’ debut novel, “Ours,” begins with a death — and a resurrection. A 17-year-old Black boy stands up shortly after a policeman fatally shoots him, as surprised as anyone else that he’s alive. He’s surrounded by the residents of the neighborhood: “Yes, they had left something behind to stand in that street together, blocked off from touching him and told to ‘Back up,’ had it yelled at them as though they were to have as little care and consideration for the boy as the ones who had shot him.”

From this contemporary opening, Williams takes readers back in time to the 1830s, when a woman known as Saint travels around Arkansas, freeing the enslaved and indirectly killing their so-called masters. She takes them to an area near St. Louis and founds a town called Ours, which she intends to keep safe and hidden from the outside world using her conjuring powers. She’s unsure where those powers came from. There’s a lot that Saint doesn’t know, doesn’t quite remember, but what she’s convinced of is that in order to keep the townspeople, called the Ouhmey, safe, she must keep them physically nearby and emotionally at a distance, for “if there’s anything more shockingly unpredictable than freedom, it’s love.”

Saint is only one of many characters whose stories unfold over the course of this deeply absorbing novel. Others include Luther-Philip and Justice, two boys born free in Ours, whose intimacy ebbs and flows through changing times and needs; Frances, whose pronouns and gender identity vary according to the eye of the beholder; and Joy, a young woman with a taste for vengeful violence, who accompanies Frances when the boardinghouse matrons they were staying with in New Orleans are murdered. Some get less page time than others but remain important. Luther-Philip’s mother, for instance, Miss Love, leaves the stage much earlier than her husband, Miss Wife, but her absence, and the way it came about, reverberates throughout the novel. Many of the characters’ conflicts and questions are never fully resolved, but that is because “Ours” is a book that embraces mystery and the unknown, whether found in conjuring and rituals or in the vagaries of lifelong relationships.

“Ours” has a fickle relationship with linearity. (I suspect it’s no coincidence that the novel’s title and town name is a homophone of “hours.”) The town’s denizens variously pass, reject, deviate from, travel through, ignore or lose time. It’s been interesting to see, then, how shorthand attempts to describe the book have leaned into the idea of Ours being an attempt at utopia, a word that doesn’t appear in the book.

* * *

A truism of our times is that the dystopia is already here — potentially a riff on a line attributed to author William Gibson, which goes something like “The future is already here. It’s just not very evenly distributed.” Dystopian fiction, John Scalzi wrote for The Times a few years ago, “lets us simulate our worst imaginings from the private security of our own homes, the better to avoid them in the real world.” The problem, of course, is that we haven’t managed to avoid many trappings of dystopian fiction: a rapidly changing climate and its attendant human displacement; the rise of fascist ideas and rhetoric; a seemingly ever-widening income gap; several ongoing genocides; billionaires building bunkers in case of some worldwide cataclysmic event. By many metrics, the dystopias we’ve been envisioning for decades no longer feel quite so escapist, nor fictional.

It’s against this background that I’ve come to notice a rise in recent fiction that explores possible utopias. Allegra Hyde’s 2022 “Eleutheria,” for example, follows its white protagonist to the titular Bahamian island and to Camp Hope, a commune attempting to address the ravages of climate change by living differently. Last year, in Gabriel Bump’s “The New Naturals,” a deeply disillusioned and grief-stricken Black couple tries to create a utopian society in a bunker in western Massachusetts, where they hope to abandon the plagues of capitalism, politics, racism and global warming. Gabrielle Korn’s “Yours for the Taking,” published in December and set in a dystopian near-future, features the troubling consequences that arise when a white girlboss billionaire decides to create a feminist utopia by cultivating a society without men, to prove that in their absence, peace and harmony will prevail.

None of these novels end up fully endorsing their various utopias, nor is that their intent. Instead, they ask tricky questions about what attempting to create an ideal society entails: What compromises of exclusion are made in the name of future equality? What fundamental human realities do we ignore in our fantasies of perfect harmony? What happens when a foundational ideology works for some but not others? Perhaps most tellingly, these books seem to conclude that it’s largely impossible to manufacture a utopia — which isn’t to say that the project is entirely unworthy, only that curation won’t be how we arrive at equality, safety and peace.

I’m wary of codifying literary trends. In part, the recognition of a trend so often depends on what subset of literature you’re looking at. Science fiction writers, for example, have long been interested in both utopias and dystopias, but those novels from Hyde, Bump and Korn were not presented strictly as science fiction. Another reason for my caution is that many “trend” labels arise from what is essentially marketing language, from book editors and publicists — such as the one who pitched “Ours” to me as being about the creation of a utopian town. For better or worse, this framing remained with me as I read the novel.

Williams writes in his author’s note at the end of the book that “Ours” is his attempt “at creating a contemporary mythology for Blackness in the United States of America.” He says he “aimed to write an epic taking place during the antebellum period where slavery is not the main antagonist without disregarding or disappearing the enslaved.” In other words, the author’s own framework doesn’t include the idea of utopia. Even so, his novel still ends up demonstrating what a utopia can look like.

Ours is a manufactured town, yes, created by Saint for the purposes of providing both safety and freedom to its people, but she refuses to be its leader, and when her meddling causes harm, she suffers consequences, losing the Ouhmey’s trust. In many ways, the 1800s Ours runs itself, without need for a mayor or a police force; it’s a communal effort whose people help one another when and as needed, even when they don’t particularly like each other. They come together to protect the town when it’s under assault, not because it’s perfect, but because it is their home, where they find joy and sorrow and love and heartbreak, where they relive the traumas of their past enslavement while also comforting one another. It is a messy utopia, unpredictable and full of conflict, which is to say it is human.

The novel’s opening indicates that the town has changed drastically in the nearly 200 years of its existence, becoming what Williams calls a hood rather than a town, suffering from the same police violence enacted against Black people all over the country, including infamously in Ferguson, Mo., a real town that like Ours sits just outside St. Louis. And yet its sense of community remains intact.

In a 2022 interview, Williams expressed his interest in navigating “the terrain of harsh realities without falling into the trap of valorizing them,” acknowledging that “rarely are moments simply pure in either direction of beautiful or ugly, peaceful or challenging.” Fictional utopias often fail because they refuse to dwell in complexity, insisting on a moral or ideological purity that ignores the lived realities of human beings and all their hurts. In this sense, “Ours,” for all its elements of magic, fantasy and mythology, is a realistic depiction of how we might arrive at utopia: through people who are always trying to become, always finding ways to navigate and survive harsh realities, always reaching for moments of joy and intimacy.

Ilana Masad is a books and culture critic and author of “All My Mother’s Lovers.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.