Opinion: The surprising way to help your brain remember

In our age of information overload, remembering things can be a daunting task. But as a memory researcher and college professor, I’ve found some hope in that challenge.

In January 2021, like millions of educators and having watched my own daughter struggle with online learning, I worried about teaching through a screen. I had spent two decades basing grades primarily on midterms and finals, but it’s tough to prevent cheating during online tests. So I had to let go of traditional methods of testing to measure learning. Then I realized I could use a different testing system — to drive learning.

In my lab, we were doing brain imaging studies based on decades-old research showing that testing people on recently viewed material dramatically increases their retention over time. Following the model in our experiments, I gave my students a three-day window to take an open-book quiz online every week, after which they could see the correct answers and either learn from their mistakes or reinforce what they got right.

People without memory problems could be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s under a plan by an influential scientific panel dominated by members with ties to drug companies.

The point of these quizzes wasn’t to torture my students but prompt them to think critically about the material regularly, with my feedback and support. The student response to this approach exceeded my wildest expectations; 85% strongly agreed that weekly quizzes, with feedback, helped them learn. (If you are not a teacher, let me assure you that students almost never say anything positive about any kind of test.)

Testing works as a learning tool because it exploits a simple principle of human brain function. We are wired to learn from our mistakes and challenges, a phenomenon called error-driven learning.

Neuroscience has shown that error-driven learning is key to learning new motor skills: We learn to make skilled movements by observing the difference between what we intend to do and what we actually do. For instance, when musicians practice a song they already know fairly well, some parts will be relatively simple, but others a struggle. Rather than recording a new memory of every part of the song each time it is played, the better solution for the brain is to tweak existing memories to better handle challenging parts.

Error-driven learning can also explain the benefits of actively learning by doing, rather than passively learning by memorizing. When you drive around a new neighborhood, you are going to learn much more about the layout of the area than if you go through the same neighborhood as a passenger in a taxi. Actively navigating a new environment gives you the opportunity to learn in real time from the outcomes of your actions.

The Senate minority leader freezes on camera. Trump mixes up “Sioux Falls” and “Sioux City.” Those are natural parts of aging, and more people would get help if we discussed them openly.

A huge number of academic studies show something similar. Comparing test results for students who read material over and over again against those who read it fewer times but repeatedly test their knowledge, it’s the latter who retain the most long-term.

Scientists don’t fully agree on the reasons why testing has such a powerful effect on memory. The simplest explanation is that testing exposes your weaknesses. In general, we tend to be overconfident about our ability to retain information. Those who are tested have the humbling, yet productive, experience of sometimes failing to recall information they thought they had learned well.

Beyond its ability to open our eyes to our weaknesses, the struggle itself may make us better learners. Computers and AI systems learn through trial and error, tweaking the connections between their artificial neurons to get better and better at pulling up the right answer. Cognitive psychologists Mark Carrier and Harold Pashler theorized that humans can learn through a similar struggle.

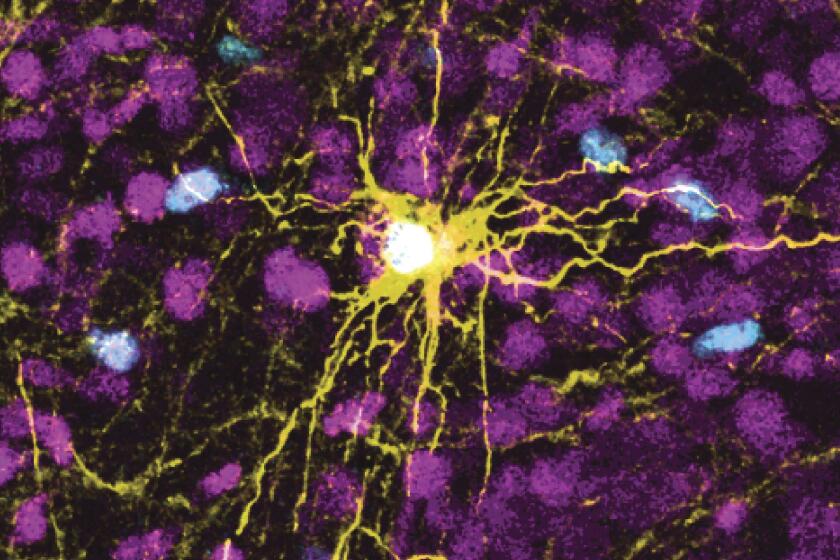

My lab found evidence to support this in a functional magnetic resonance imaging study, where we found that testing increases activity in the hippocampus, a memory center in the brain. In our study, we used our “hippocampus in a box” computer model that simulates how this brain structure supports learning and memory. We saw that the benefits of testing don’t come from making mistakes per se, but rather from challenging yourself to pull up what you’ve learned.

When you test yourself, you try to generate the right answer, but the result may not be quite perfect. Your brain will come up with a blurry approximation, creating a struggle to get it right that provides opportunities to learn more.

This week’s L.A. Times News Quiz touches on a handful of record-setting Oscar nods, two high-rise developments and one particular Taylor Swift birthday gift.

Stress testing your memory like this exposes the weaknesses in connections between neurons so the memory can be updated, strengthening useful connections and pruning the ones getting in the way. Rather than relearning the same thing over and over, it’s much more efficient to tune up the right neural connections and fix just those parts that we are struggling with. Our brains save space and learn quickly by focusing on what we didn’t already know.

Although we usually benefit from error-driven learning, there is one important condition: It works if you eventually get close to the right answer, or at least if you can rule out wrong answers. You don’t benefit from mistakes if you have no idea what you did wrong.

Another influential factor is the timing of your learning. Virtually all students, my past self included, have crammed for exams. While my all-nighters worked in the short run, most of what I had learned would slip away just days after the end of the semester. I’m not alone; a mountain of findings in psychology show that you can generally get much more bang for your buck by putting gaps between learning sessions rather than by spending the same amount of time cramming.

To understand why that might be, suppose you read my latest article on episodic memory while sitting on the couch in your living room, then the next day you reread it at the beach. At first, the hippocampus can pull out the memory of the last time you read the article, but it will struggle a little because you’re seeing the same information in a different context. As a result, coalitions of neurons in the hippocampus reorganize to place more emphasis on the content of what you read, so the information is less tied to where and when you first read it.

Scientists at Stanford transplanted human brain cells into the brains of rats, where they grew and formed working connections.

Computer modeling helps show how, if you keep returning to the same information periodically, the hippocampus can continually update those memories until they have no discernible context, making it easier to access them in any place at any time.

Error-driven learning tells us that whether you are trying to learn surfing, Spanish or sociology, if it comes effortlessly, you aren’t getting the most out of your experience. Even if it’s not pleasant, struggling with information can be a good thing. It often means you’re really learning.

Charan Ranganath is a professor of psychology and neuroscience at UC Davis. This essay was adapted from the author’s forthcoming book, “Why We Remember: Unlocking Memory’s Power to Hold on to What Matters.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.