Opinion: I’m a CSU professor, and the administration’s response to faculty needs is an insult

At 52, I am abundantly educated, with two bachelor’s degrees, a teaching credential, a master’s degree and a doctorate completed while raising three children. Yet my daughters can earn more money than me in their 20s. I am a California State University professor. And one of the higher paid, privileged ones at that.

I knew becoming an educator would not make me wealthy. As I worked diligently for years to earn tenure and promotion to the rank of associate professor and then the rank of professor, I did my job joyfully. Maybe I didn’t earn as much as the lawyer my late father wanted me to be, but I had a job I loved, a positive work environment and decent pay.

Until now. In negotiations with the California Faculty Assn. representing 29,000 faculty in the CSU (the largest public university system in the United States), management walked away from bargaining and imposed its last, best and final offer of only a 5% salary increase.

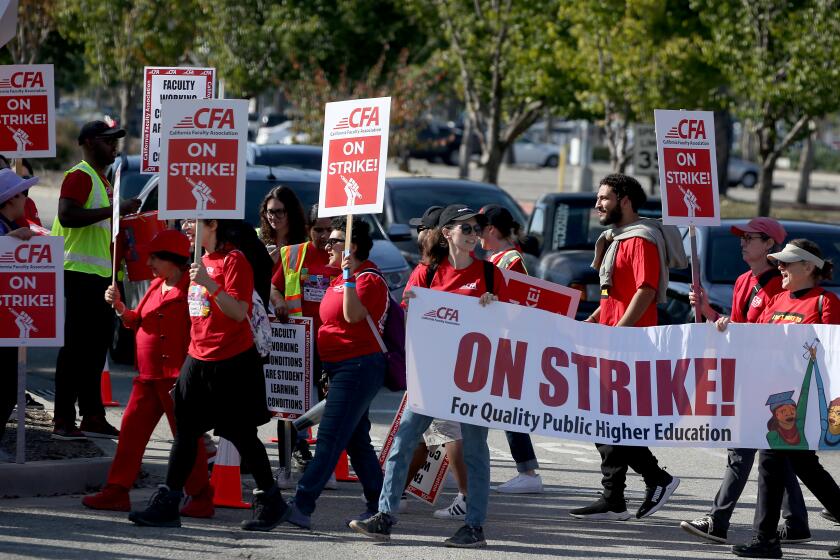

The raise does not end the divide over pay between the faculty union and CSU, a dispute that had reached an apex in recent weeks, with one-day strikes at four campuses in early December.

This offer is insulting. I prepare future generations of special education teachers, but my salary is lower — by around $22,000 a year with my doctorate — than what I would be earning if I had remained a teacher in Arcadia Unified School District — admittedly a district that pays teachers well. I know I also earn less compared with peers at California’s community colleges and the University of California. And that gap will continue to widen — not only for me, but also for other faculty who work just as hard and happen to be on the lower rungs of the CSU salary schedule.

CSU’s 5% offer falls far short of the CFA’s proposal of a 12% raise, which would keep pace with inflation since 2021. (According to consumer price indexes, CSU faculty have lost 10% in purchasing power during this time period; the CFA pay request would actually amount to a 2% raise.) To make matters worse, we’ve been informed that parking fees will be increased by 15%.

The union also proposed to increase the salary floor for our lowest-paid lecturers and establish more reasonable workloads, longer parental leaves, better counselor-to-student ratios (on my campus, this ratio is 1 to 4,000; it should be 1 to 1,500) and more lactation spaces and gender inclusive bathrooms on campuses. The CSU bargaining team ignored most of these proposals and canceled bargaining sessions.

During week-long, rolling walk-outs at four California State University campuses, faculty highlighted the tenuous working conditions of lecturers, who are a backbone of instruction but ineligible for tenure.

The faculty gets emails from at least one administration manager — whose salary I know is three times mine — saying that CSU cannot afford to raise our pay more than 5% or meet our working-conditions demands. Chancellor Mildred Garcia would deny the university’s lowest-paid lecturers, who start at $54,360 a year, a $10,000 raise on that floor, even as she earns a compensation package of nearly $1 million annually.

And CSU contends that its $8.6 billion in reserve cannot be touched because it may be needed in case of an emergency. Faculty walking off the job the first week of the spring semester (and potentially for longer) to strike for dignified wages is an emergency.

Students pay tuition — which the CSU Board of Trustees recently voted to increase by 34% over the next five years — because they want to enroll in classes with professors who are engaged with them, not exhausted from working second and sometimes third jobs just to survive in these economic times.

The faculty union and the Cal State system remain divided in contract negotiations. Faculty want a 12% raise for 2023-24, but the system says it is not possible.

The state funds CSU because its faculty educate nearly 500,000 students who then become nurses, engineers and other professionals in California. Nearly 50% of the K-12 teachers in the state are educated at a Cal State campus.

And yet, CSU spent less than 34% of its budget on instruction in 2022.

Over the last 15 years, according to an analysis last month by CalMatters, full-time CSU lecturers saw raises of 22% on average since 2007, while the base pay of presidents at the 23 Cal State campuses rose 43% on average. The biggest category of personnel increases in 2018-2022 was among administrators, not instructors.

And where did the system’s $8.6 billion in reserves come from? It was built on the backs of faculty and staff. According to a CFA-commissioned independent financial analysis, Cal State’s operating cash flow surpluses (they’ve existed every year between 2015 and 2022) could cover the difference between the administration’s offer and the CFA proposals without dipping into reserves. Yet management prefers to invest in itself and the stock market rather than faculty and staff.

Saving for an emergency is important, but only after covering essential expenses.

On Jan. 22, professors, lecturers, librarians, coaches and counselors at all 23 California State University campuses will walk off the job. Will management finally recognize that investing in us and our working conditions is essential?

Leila Ansari Ricci is a professor of special education and a past department chair at California State University, Los Angeles.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.