Opinion: The Elvis of the literary scene is L.A.’s own Raymond Chandler

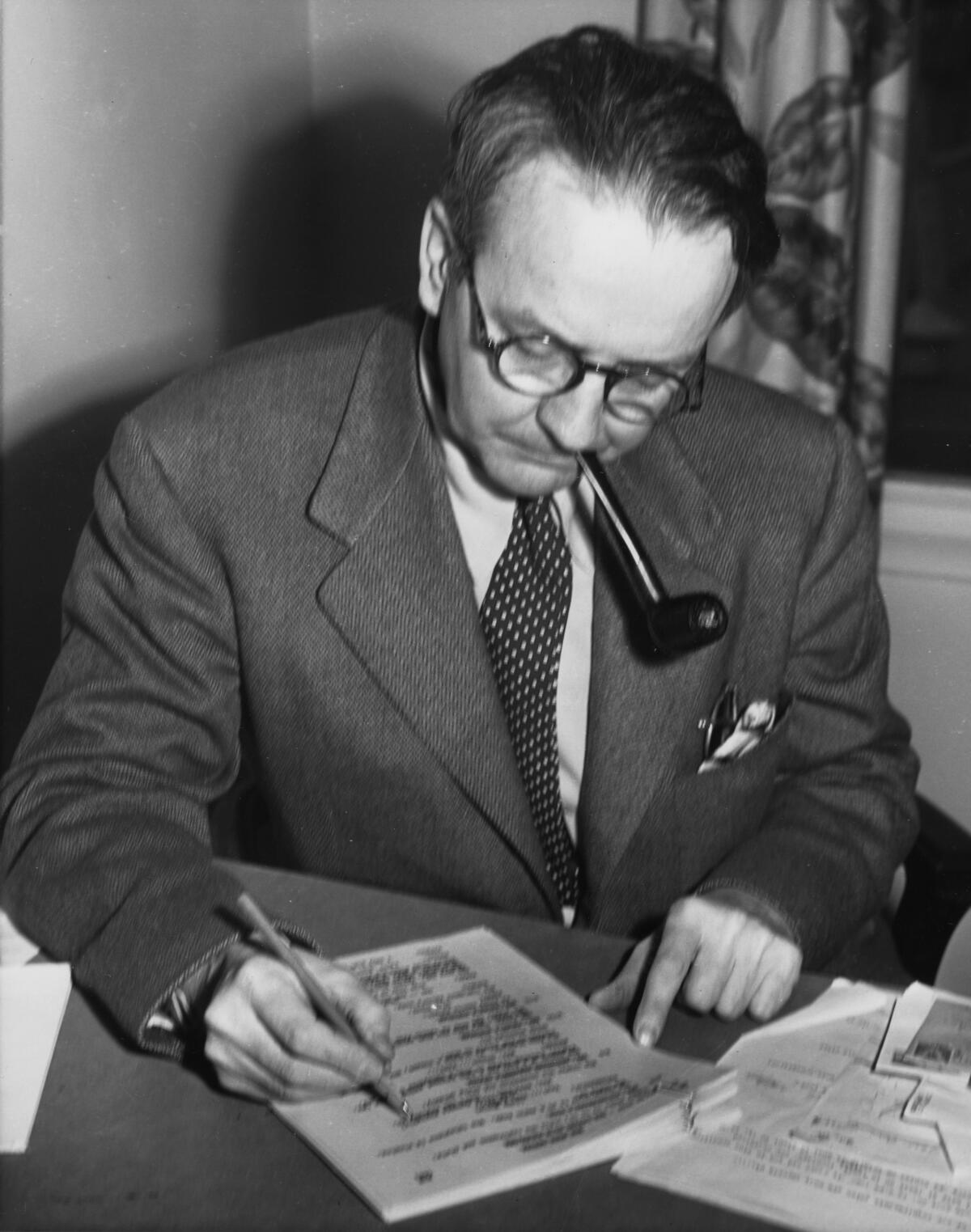

In mid-December I opened my computer to find a slew of emails from friends. They all sent the same article from the Guardian, with the headline “[R]are Raymond Chandler poem discovered by US editor.” A long-lost poem had been unearthed by the managing editor of the Strand magazine, Andrew Gulli, who found it in a shoebox in the Chandler archive in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University.

Chandler is one of my literary passions. In 2007 I published a biography of him, “The Long Embrace,” a book that was not only a portrait of a writer but of a city, Los Angeles, where he had lived in almost 40 different residences, and of a marriage.

Flawed heroes, dark angels and dashed dreams: Why L.A. and noir are synonymous

Chandler was utterly devoted to his wife, Cissy Pascal. He called her “the beat of my heart.” As a writer, he said he “never really thought I was anything more than a fire for Cissy to warm her hands at,” even though she hadn’t much cared for his hard-boiled novels, finding them too harsh for her deeply romantic sensibilities.

The poem that Gulli found was written a few months after Cissy’s death in 1955, when Chandler was so distraught at losing his wife that he’d become suicidal. Titled “Requiem,” it is a lyrical cry from the heart: It begins, There is a moment after death when the face is beautiful / When the soft tired eyes are closed and the pain is over, / And the long, long innocence of her comes gently in / For a moment more in quiet to hover — and then the refrain begins, But there are always the letters. It is her letters he’ll treasure, letters that “will not die.”

As Philip Marlowe Might Say, He’s a Mystery Man Who Knows the Score

As I began reading the lines quoted in the Guardian, I had an instant feeling of recognition. I knew this poem! I had seen it in the Chandler archive at the Bodleian Library too — in fact, I had quoted it in “The Long Embrace” in its entirety, though I didn’t note its title. The long-lost poem was not long-lost at all.

I kept getting more emails. I was astonished at how quickly and widely the story was picked up by the Smithsonian Magazine, ABC News, NPR and the New York Times. It lit up the internet.

Steph Cha, author of ‘Your House Will Pay,’ explains how Raymond Chandler’s ‘The Big Sleep,’ her neighbor on the Ultimate L.A. Bookshelf, changed her life.

“Exciting stuff, eh?” wrote one friend about the remarkable “find.” No, I thought, irritably. (Ultimately, many of the stories got corrected to note that the poem was in my book.)

One of my correspondents, a Chandler fan, explained the whole giddy hubbub this way: “Ray is the Elvis of the literary scene. There’s the same undying level of interest.”

The Elvis of the literary scene ... Wow. How true, I thought. Chandler, the literary figure, had the same kind of iconic appeal that Elvis the rock star had, or Marilyn the actress. They all fall into that club of special people of whom we can never get enough.

Books have been written — movies made — analyzing why certain cultural figures become icons and continue to exert such power in our collective consciousness (think “Priscilla,” “Elvis” and “Marlowe,” all recent films), and yet for all the love thrown their way, and for all the attention they draw year after year, they remain beyond conclusive reading, inexhaustible and irresistible subjects. Why do they hold our attention so powerfully, crossing all levels of society and cultures?

In 1932, a 44-year-old oil company employee walked out of the Bank of Italy building at the corner of Olive and 7th streets in Los Angeles for the last time.

Chandler once said that only he and Marilyn Monroe had managed to “reach all the brows” — highbrow, lowbrow and middlebrow — an observation echoed by the director Billy Wilder. “It’s a peculiar thing,” Wilder said, “you know, in all the 40 years plus that I have been in Hollywood ... the two people that I’ve been connected with whom everyone is most interested in are Marilyn Monroe and Raymond Chandler. There is some kind of fascination, as well there might be, because they were both enigmas.”

What Gulli really discovered, and what the flurry of December news reminded us of is the enduring power of Raymond Chandler’s appeal, the allure of his stories. How strongly his personality and his extraordinary novels continue to speak to readers, with their darkly humorous vision of a violent and corrupt America. He was a great stylist who spawned generations of imitators. He put Los Angeles on the literary map and made the lowly mystery into a respected literary form. He captured the zeitgeist. His appeal is beyond facile explanation. He is indeed the Elvis of the literary scene.

And he has the press to prove it.

Judith Freeman is the author of one short-story collection, five novels, two nonfiction works and numerous essays and articles in the Los Angeles Times and other publications.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.