Opinion: Saying goodbye to Kissinger the criminal

It is oddly appropriate that Henry Kissinger should have died in the year that commemorates the 50th anniversary of the 1973 military coup in Chile — the cataclysmic overthrow of its democratically elected president, Salvador Allende, and the end of a fleeting attempt to create a socialist society without resorting to violence, a first in the history of revolutions.

As national security advisor to President Nixon, Kissinger ferociously opposed Allende and destabilized the Chilean government by every means possible. He considered that, were Chile’s peaceful movement for social and economic justice to succeed, American hegemony would suffer. He feared that the example might spread and affect the world balance of power.

And Kissinger not only fostered the ousting of a democratically elected foreign leader, he subsequently supported the murderous regime of General Augusto Pinochet, even as the dictatorship was massively violating the human rights of Chile’s citizens, most egregiously in the cruel and terrifying practice of “disappearing” opponents.

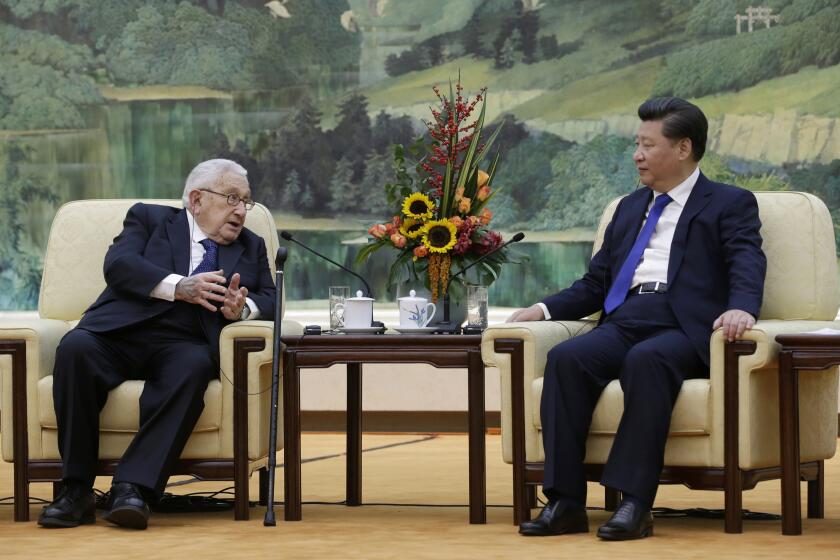

The former secretary of State, the architect of U.S. foreign policy at the apex of the Cold War and a towering force in world affairs, dies at 100 at his Connecticut home.

It is these desaparecidos whom I think about now, as Kissinger is feted by a shameless bipartisan Washington elite. All these years after the coup in Chile, 1,162 men and women are still unaccounted for. The contrast is telling and significant: Kissinger will have a memorable, almost regal, funeral, while the victims of his policies have yet to find a small place on Earth where they can be buried.

If my first thoughts, when I heard the news about Kissinger’s death, were filled with memories of my missing Chilean compatriots — several of them had been dear friends — soon enough a flood of other casualties came to mind: the countless dead, wounded and disappeared in Vietnam and Cambodia, in East Timor and Cyprus, Uruguay and Argentina. The Kurds Kissinger betrayed; the apartheid regime in South Africa he bolstered; the Bangladeshi dead he belittled.

I always dreamed that a day would come when Kissinger would stand in a court of law and answer for his crimes.

It almost happened. In May 2001, Kissinger was sojourning at the Ritz Hotel in Paris when he was summoned to appear before French Judge Roger Le Loire as a witness in the case of five French nationals who had been disappeared during the Pinochet dictatorship. Rather than take that occasion to explain himself and vindicate his reputation, Kissinger immediately fled France.

Anthony Bourdain’s remarks on Henry Kissinger go viral in the wake of the former secretary of State’s death.

Nor was Paris the only city in which he was pursued. Spanish Judge Baltazar Garzón unsuccessfully requested that Interpol detain the former U.S. secretary of State to answer questions in the ongoing trial of Pinochet for human rights violations (the general was arrested in London but finally remanded to Chile, where he died, never convicted, in 2006).

Nor did Kissinger deign to respond to Argentine Judge Rodolfo Corral about the infamous and lethal U.S.-backed Operation Condor in Latin America, or to Chilean Judge Juan Guzmán about the murder of American citizen Charles Horman in the days just after the coup (a case that inspired the Costa Gavras film “Missing”).

Reactions to the ex-secretary of State’s death range from praise for his defense of U.S. interests to denunciation of him as a war criminal.

And yet I nursed the impossible dream: Kissinger in the dock. Kissinger held accountable for so much suffering. A dream that vanished with his death.

The more reason for that trial to happen in the court of public opinion. The disappeared of Chile, the forgotten dead of all those nations Kissinger devastated with his “realpolitik,” are crying out for justice.

I do not wish that Kissinger may rest in peace. I hope, on the contrary, that the ghosts of those multitudes he damaged beyond repair will trouble his memory and haunt his history.

Whether that happens depends, of course, on us, the living, on the willingness of humanity, amid the din and deluge of praise and eulogies, to listen to the hushed, receding voices of Kissinger’s victims and vow never to forget.

Ariel Dorfman is the author of “Death and the Maiden” and, more recently, “The Suicide Museum,” which investigates the death of Salvador Allende.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.