Editorial: Supreme Court’s new ethics code falls short in solving its ethics problem

The U.S. Supreme Court justices have adopted a code of conduct designed to assure Americans that they will behave ethically. The document released by the court last week, however, falls short of addressing all the concerns that have been raised about the justices’ outside activities and possible conflicts of interest. It also perpetuates a system in which individual justices have the final say about whether they will participate in a case.

Unlike lower-court federal judges, justices aren’t bound by the Code of Conduct for United States Judges. In 2019, Justice Elena Kagan said that Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. was studying a possible code for the court, but justices were apparently unable to reach a consensus.

There’s no system to force recusals when there are conflicts of interest.

Now, after embarrassing news reports about questionable conduct by some justices, it finally has brought forth a document designed to dispel “the misunderstanding that the justices of this court, unlike all other jurists in this country, regard themselves as unrestricted by any ethics rules.”

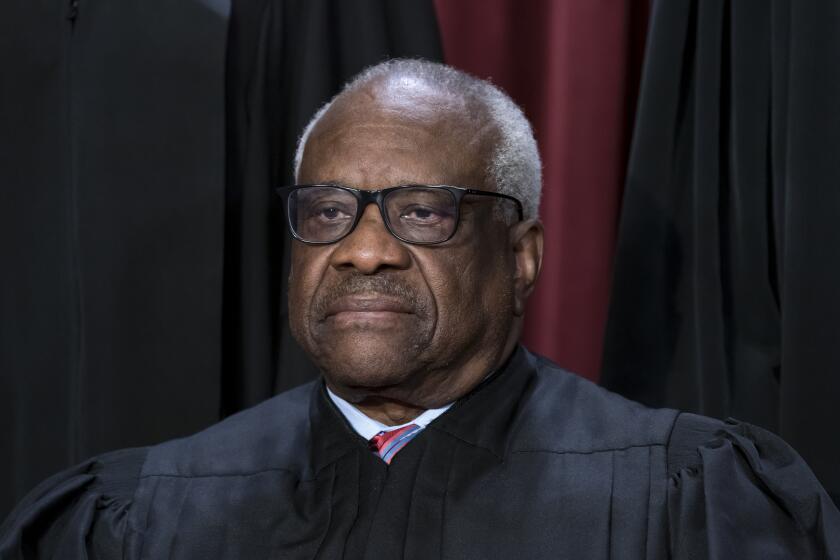

The new code — which the justices call “a codification of principles that we have long regarded as governing our conduct” — is endorsed by Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel A. Alito Jr., who were the subject of news reports describing their undisclosed luxury vacations paid for by wealthy individuals. Both justices have said they didn’t believe they were obliged disclose the information. Earlier this year the Judicial Conference of the United States clarified its guidance to say that judges must disclose travel by private jet.

A new term is beginning with cases on gun rights and administrative agencies already on the docket. Later, the court is likely to decide whether Donald Trump is disqualified from running for president.

That the court finally adopted a code of its own shows that the justices can be influenced by public and congressional criticism. That doesn’t mean the code goes far enough. Amanda Frost, a judicial ethics expert at the University of Virginia Law School, told The Times that it was “a small but significant step in the right direction.” But Frost also noted that there was “no acknowledgment of past transgressions, no enforcement mechanism and no guarantee of increased transparency or accountability.”

The lack of enforcement is particularly a problem when it comes to requiring justices to refrain from participating in cases because their “impartiality might reasonably be questioned” — so-called recusal.

A new ProPublica report reveals the jurist’s pattern of secretly accepting luxury private jet and yacht travel from a cadre of conservative billionaire donors.

Recusal is admittedly a more complicated matter for Supreme Court justices than for lower-court judges, because a justice who withdraws from a case cannot be replaced the way a lower-court judge can be. According to the new code, the “rule of necessity may override the rule of disqualification.” A commentary attached to the code explains that the loss of one justice is “effectively the same as casting a vote against the petitioner.”

Even so, there are some circumstances in which recusal by a justice is necessary to maintain public confidence in the court. For example, it seems obvious that Thomas, whose wife, Virginia, was involved in efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election, should not sit on any case arising from the prosecutions associated with attempts to overturn that election or the riot at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

Nor should an individual justice be the sole judge of whether he or she should recuse. In a recent op-ed in The Times, Erwin Chemerinsky, the dean of the UC Berkeley School of Law, cited two proposals for changes in the recusal process: the appointment by the chief justice of retired appeals court judges to decide recusal questions and, alternatively, a procedure in which a justice’s eight colleagues would decide whether recusal was necessary.

It’s important that the court toughen its ethics policies because it is unlikely that proposals in Congress to increase transparency and accountability at the court will win the necessary bipartisan support any time soon.

In July, the Senate Judiciary Committee approved the Supreme Court Ethics, Recusal and Transparency Act, which would strengthen ethics enforcement and provide a mechanism for reviewing a petition that a justice be disqualified from a case. But Republican leaders decry ethics reform as an attempt by Democrats to punish a conservative court whose decisions they don’t like.

That means maintaining the court’s integrity will be up to the justices. They should regard the promulgation of its new code as just a small step toward repairing the institution’s reputation with the public.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.