Editorial: We know how to turn students into better readers. Why doesn’t California do it?

More than half of California students can’t read at grade level, the latest set of scores from the state shows. It’s just the most recent sign in a too-long line of evidence that students aren’t learning this educational basic and are slipping further behind. The incremental progress made in years past was sent reeling backward during the pandemic.

That’s what made it particularly heart-sinking to see the figures from the spring 2023 round of testing. With everyone back at school for more than two years by then, and with some level of normalcy restored, there was reason to hope that reading scores would have reached, if not pre-pandemic levels, at least some level of improvement.

Instead, the percentage of grade-level readers crept down ever so slightly, from 47.1% to 46.7%.

Giving residents censorship rights over librarians and the public crosses a clear line that should never be breached.

If there’s one academic skill that students must master, reading is it. Literacy is a portal through which almost every other subject can be learned. Even math, at least theoretically.

What makes all this so frustrating is that we know by now what makes for better reading instruction. We’re just not doing it.

Schools nationwide have clung for too long to methods of teaching reading that banished phonics and related skills to a dark corner of the classroom. But the evidence has been clear for more than two decades that phonics and reading taught through a structured approach led by teachers were key parts of the educational process.

L.A. Unified officials need to explain to parents why they slashed Primary Promise, a program that has helped struggling students improve their reading and math achievement.

For a long time, schools of education embraced the “whole language” method, which held that reading comes naturally to children. Students needed engaging literature through which they would recognize whole words rather than individual sounds, the theory went, which would lead them to easily decode letters into words. It worked for some students; it’s estimated that about 30% of students will learn to read well under any method. Others will struggle.

A similar method called balanced literacy included a tiny bit more phonics. That worked so badly that Columbia University recently closed its center devoted to balanced literacy.

There’s a growing body of evidence that a more comprehensive method is best. Generally called “science of reading,” it has unfortunately been misinterpreted as teaching literacy almost solely through phonics, in which students are taught to sound out words from letters. It evokes images of bored students struggling painfully through the letters of each word, with little opportunity to understand, much less enjoy, what they were reading.

The number of American kids reading for pleasure just fell — again. Parents and schools can do something about that.

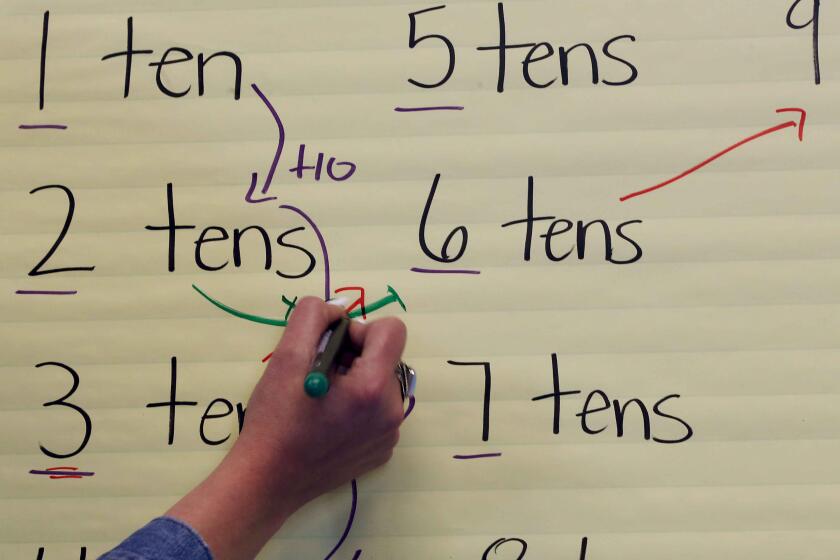

Learning to read is a complex process that requires phonics and related skills, with students directed by a teacher through the decoding of letters into sounds, sounds into words, words into sentences and stories. But it also requires building children’s vocabularies as well as their enthusiasm for literature.

And evidence shows they learn to read better when they, to put it simply, know things. If they’re reading about owls, they’ll catch on to reading more quickly and thoroughly if they also have studied owls. They need to gain enough reading speed for the sentences to make sense. All of these are part of the science of reading, and dismissing it as phonics could be as disastrous as expecting students to just pick up reading through whole-language exposure.

The concept is gaining traction. By late July, 32 states, New York City and the District of Columbia had adopted policies favoring science of reading, according to an analysis by Education Week.

Though some of that is happening in California, the state has been slower than most to embrace the science of reading.

We’ve made some movement toward improving reading instruction, including allocating nearly $500 million in the last year to place reading specialists at low-performing schools. State Supt. of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond, who agreed in an interview that phonics instruction has been proving its value, has been a proponent of teacher-training materials based on the science of reading, and pushed for legislation — Senate Bill 114, which goes into effect in 2024 — to screen all schoolchildren for dyslexia and other reading-related learning difficulties.

That’s all good. It’s also not enough. Thurmond says he is leery of telling schools how to teach reading, but as he notes, the evidence is in. The state should require effective reading instruction in its schools, or at least the ones where scores are low or stagnant, based on that evidence, which would include many Los Angeles Unified schools.

A switch to science of reading led to significantly improved reading levels at 75 of the lowest-scoring schools in California, said Mark Rosenbaum, a public-interest lawyer who won a $53-million settlement from the state over its failure to teach reading adequately. The schools were assigned to a reading expert who overhauled teaching methods to include more phonics and direct instruction.

Bringing phonics out of the shadows won’t magically turn students into top-notch readers. But it can definitely bring about large-scale improvement and should be the state’s highest educational priority over the next few years.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.