Opinion: The world is scarier than Halloween. I found refuge in Black horror stories

Why do we love Halloween? Is it that we all like to be scared? Or maybe it’s that we want to conquer our fears? I recently took my two young sons shopping for Halloween decorations. Halfway down an aisle stocked with hanging ghouls, misting cauldrons and spiders, my 8-year-old looked around, nervous and slightly trembling. The whole vibe was making him uneasy. Why was I surprised? We were surrounded by literal monsters, images that should scare any living person. A life of consuming and participating in entertainment taught me these props were harmless. They couldn’t hurt me.

I found myself reflecting on my own journey with fear. I grew up in a single-parent home in Washington, D.C. Despite being the loved and valued baby of a big Southern family, early encounters with death made me an anxious kid. My godmother died of lupus when I was 7. I remember her lying there in her coffin, eternally still and cold. During my summers in southern Virginia, I made note of how often my grandmother attended funerals. Death seemed to lurk just around the corner; its peeping eye kept me up at night. When would it come? For my grandmother, for my mom, for me? What was on the other side? Would it hurt?

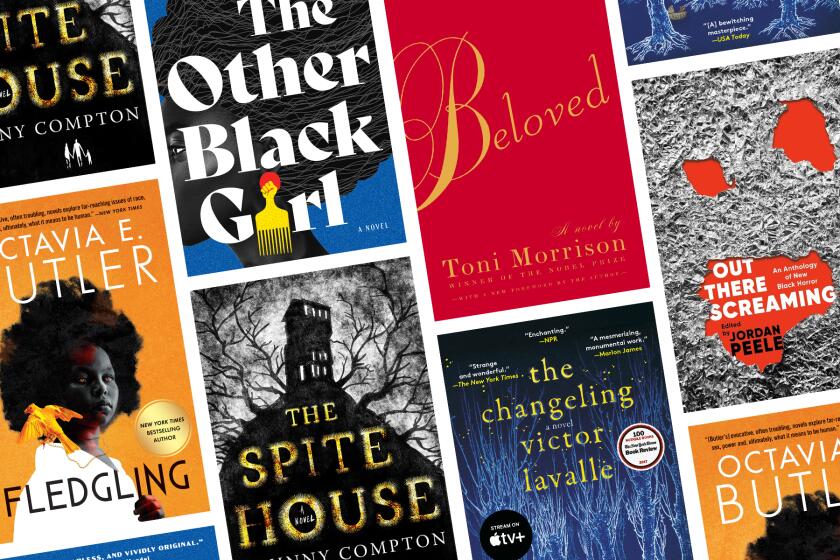

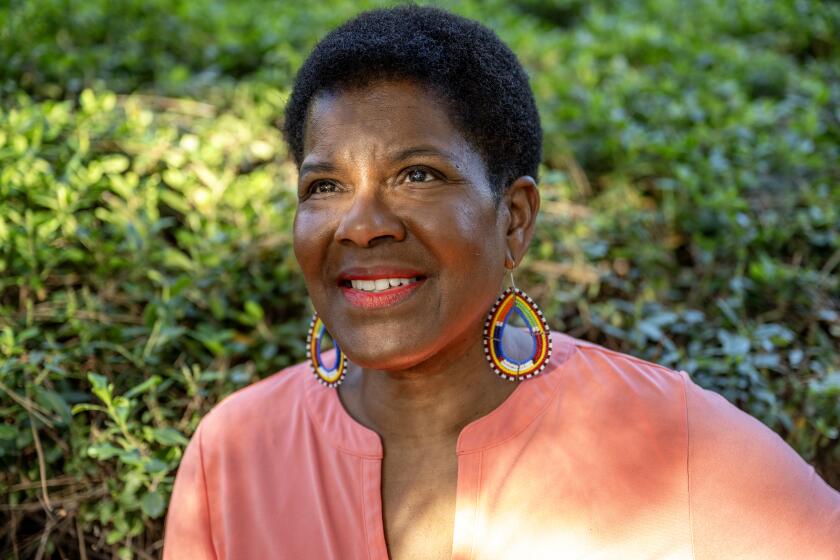

Black horror pioneer Tananarive Due helps us pick 6 great books from the genre, from a Toni Morrison classic to a new anthology by Jordan Peele.

I found refuge in horror. As a kid, I read R.L. Stine’s “Goosebumps” fiction series filled with monsters, haunted masks and shrunken heads. But I knew they weren’t real. The ghouls and goblins I let into my mind didn’t make an already sleepless night worse. They didn’t lurk underneath my bed. Instead, they offered wonders and “what ifs.” How might I escape a haunted house?

The possibilities were endless. And with them, I found some peace. For a while.

On Samhain, a festival celebrated by ancient people, the lines between the Otherworld of the dead and the realm of the living were weakened.

I was 14 when 9/11 smoke rose from the Pentagon, something I could see clearly from my Northeast D.C. high school. As my fears sprouted into nightly worries of a sudden, blinding flash ushering in a wall of nuclear wind, my taste for horror also expanded with Stephen King, Clive Barker, Peter Straub and other writers. I consumed scary movies and horror novels to occupy myself with a range of emotions that felt safe. Because I was ultimately in control. Because I chose them. Again, I found some peace. For a while.

When my closest cousin, Michael, was shot and killed at the age of 25, my childhood worries solidified into adulthood anxiety. At 17, I developed the most existential fear of all: that of a life wasted. I would go on to college while my cousin went into the ground. I had the opportunity to make something out of my life, to love, create, become a parent. What if I failed? What if I didn’t earn my survival? I harnessed these fears into discipline and motivation. I had no other choice than to become successful. Just like those “Goosebumps” books, I took back control of my fears and used them to benefit me.

Tananarive Due’s new novel, ‘The Reformatory,’ is the latest in a career of Black horror fiction. It began with an upbringing steeped in civil-rights activism.

And then came parenthood.

After spending a lifetime reading about it, I thought I knew what fears to expect in becoming a parent. Keeping a whole other human alive, sorting through both wanted and unwanted parenting advice, enduring restless nights. And then the bullies, the rebellious years that may or may not last past adolescence. The deep desire for them to somehow become happy adults both because of and in spite of my parenting. Those worries all were and continue to be there. Each would be more than enough on its own. But raising Black boys also comes with a wariness of society’s inevitably imposed characterizations. It means fear of law enforcement, fear of stereotypes, fear of punishment for being the “other.” And what about my youngest? How do I help my little Black girl navigate a world that will age her too soon and impose flawed concepts of success, beauty and autonomy?

The wonder I felt when I was given full-size candy while trick-or-treating as a child has come to rule my recent adult life, at least as it relates to Halloween.

With reflection, I realized these fears were rooted in a long generational history that traced back across the Atlantic. How much had I learned? How much had I inherited? Once again I turned to horror to process and retake control. This time, in the form of my own writing. The Black experience offered a fresh canvas for creativity and discovery. Could I create worlds that helped me understand the George Floyds and Breonna Taylors? And, more importantly, could I share that understanding with others?

Black horror warns us of what humanity is capable of — what racism is capable of inflicting onto Black and brown bodies. Not only does it allow me, the writer, to conquer my fears on a whole new level, but it also creates better understanding in a world that’s scariest when ignorant. In recent years, we’ve seen many examples of Black horror and science fiction films and TV shows, from Jordan Peele’s movies and the “Candyman” reboot to “Lovecraft Country.” But there’s potential for so much more.

In a weird way, I was happy to see my son’s fear at that Halloween decoration store. He had the innocence to be afraid of witches and werewolves and oversized spiders. He has yet to learn the horrors of the Black experience. Maybe that’s why I write, to make the world a little bit more ready for him.

Justin C. Key is a psychiatrist and writer based in Los Angeles, and the author of the recent short story collection “The World Wasn’t Ready for You.” @JustinCKey

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.