Editorial: Newsom throws South L.A. under the broadband bus

More than two years ago, Gov. Gavin Newsom approved what was then the nation’s largest-ever investment in public broadband. The $6-billion spending plan was supposed to finally bridge the digital divide that has left too many households and businesses in low-income and rural communities without fast, reliable internet access.

But last month the Newsom administration cut projects in some of the neediest, most disconnected communities in the state, including South and Southeast Los Angeles and East Oakland, while adding projects in some of the most affluent, tech-connected communities, including Beverly Hills and Culver City.

The reasons for the changes are neither clear nor satisfying. There’s still time for Newsom to reconsider before it turns into a boondoggle. There’s also a need for the Legislature to exert more oversight and influence over the spending plan. If the program’s disparities are not addressed, California’s historic investment in public broadband will again leave low-income urban communities behind.

Nearly half of the U.S. isn’t connecting at broadband speed, study finds. In California, 1 in 6 households is not online or uses only a smartphone.

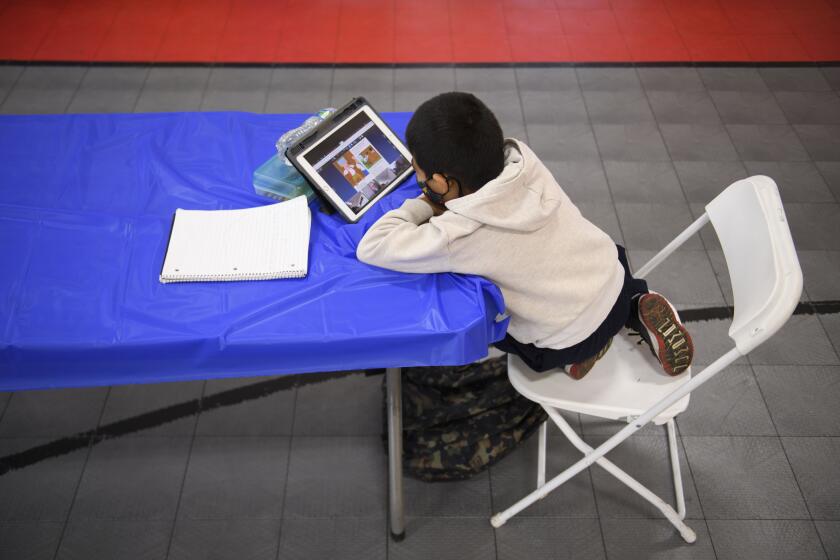

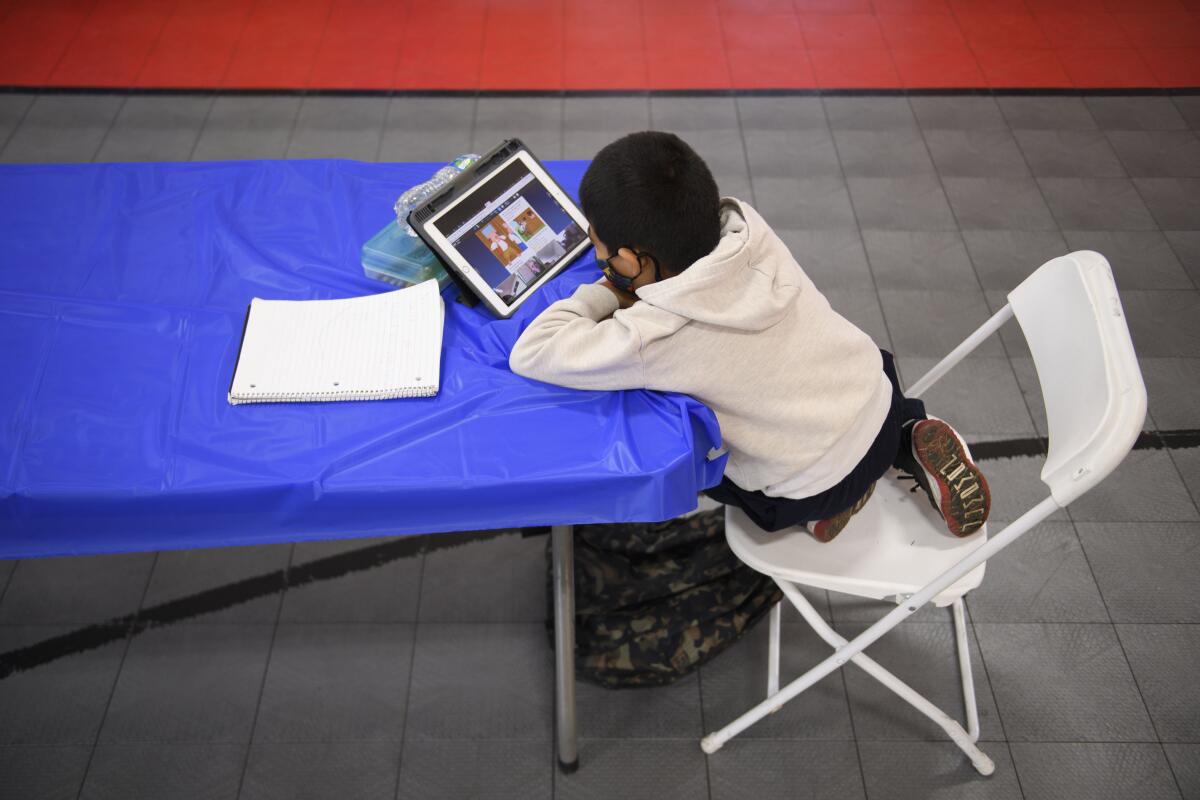

The COVID-19 pandemic made apparent the gaping digital divide in California, where roughly 2 million households did not have broadband in 2020. Online school, remote work and telehealth are practically impossible without it. But that service isn’t available in some low-income communities or is too expensive, often with higher prices for lower-quality service than in affluent areas with more customers.

The Middle Mile Broadband Initiative, which is part of the spending plan, taps $3.25 billion from the federal COVID-19 stimulus package to install high-capacity fiber optic cables in areas where the private sector hasn’t built broadband infrastructure — typically rural and low-income communities.

Eighty-seven percent of white households had access to high-speed internet, compared with 83% of Black households and 80% of Latino ones, according to a survey.

The middle-mile network connects the massive, high-speed lines that cross states and regions with the local “last-mile” service that delivers broadband service directly to homes and businesses. By installing publicly owned middle-mile fiber optic lines, California would make it easier and cheaper for cities, nonprofits and broadband companies to build the last-mile connections to homes and businesses. California set aside an additional $2.75 billion in federal aid to help underserved communities pay for last-mile projects. But without the middle-mile infrastructure, it becomes impossible or extremely expensive to build the last mile.

In 2021, Newsom announced 18 projects across the state that would build or acquire 10,000 miles of middle-mile network, mostly along highways to take advantage of the public right of way. The list included South and Southeast Los Angeles, with fiber installation planned along the 110, 105, 710 and 605 freeways, between downtown and Long Beach. The area includes communities with some of the highest rates of disconnected households in the state.

We need to avoid thinking children will recover from the past year without mental health support. Young people are resilient, but they are vulnerable.

But when the final map was released last month, most of the South L.A. projects were gone and a new line was added next to Beverly Hills and Culver City, some of the best-connected communities in the state. There were similarly confounding changes in the Bay Area, with projects in low-income East Oakland cut while projects in wealthier suburbs, such as Walnut Creek and Livermore, will be funded.

The reason? Facing higher construction costs, the state decided it could afford to build only 8,300 miles. The other 1,700 miles, including in L.A. and Oakland, were moved in Phase 2 and may be built later if the state can come up with more funding. Officials with the state Department of Technology and California Public Utilities Commission said that in making the cuts, they prioritized unserved communities — meaning areas that have no service.

But the maps they used to determine which areas need service are seriously flawed, overstating service in poor areas and understating it in affluent ones, digital equity advocates say. The agencies have acknowledged the maps have problems but proceeded anyway. It’s irresponsible to base billion-dollar, once-in-a-generation funding decisions on bad data.

State officials said they chose to save money on L.A. County projects by leasing part of an existing private line that runs through Beverly Hills and other affluent areas in order to bolster service further down the line. But the line is still far from communities of highest need.

This decision is an affront to the Crenshaw district, South Gate, Lynwood, Paramount and other communities that have spent nearly two years planning last-mile investments based on the Newsom’s administration’s announced plans and will now have to scramble for additional funding or scrap their plans.

“How can you make an argument that that is a good use of money intended to close the digital divide?” asked Shayna Englin, director of the Digital Equity Initiative at the California Community Foundation. “We have this opportunity to solve this problem for generations and we’re not going to do it.”

Newsom and lawmakers cannot let this funding go to waste, or they’ll be remembered as the leaders who failed to bridge the digital divide.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.