Last month’s killing of Laura Ann Carleton for flying a rainbow flag in Lake Arrowhead came shortly after the fatal stabbing of O’Shae Sibley, a Black gay man who was dancing to Beyoncé at a Brooklyn, N.Y., gas station.

In this climate of hate and attacks on LGBTQ+ people, loving the enemy can seem worse than a cliche. In some far-left and far-right circles, it’s immoral.

For the record:

10:29 a.m. Sept. 4, 2023An earlier version of this column incorrectly stated that the American Psychological Assn. removed homosexuality from its manual of mental illnesses. It was the American Psychiatric Assn.

How can we respond? Will hating the haters help?

Opinion Columnist

Jean Guerrero

Jean Guerrero is the author, most recently, of “Hatemonger: Stephen Miller, Donald Trump and the White Nationalist Agenda.”

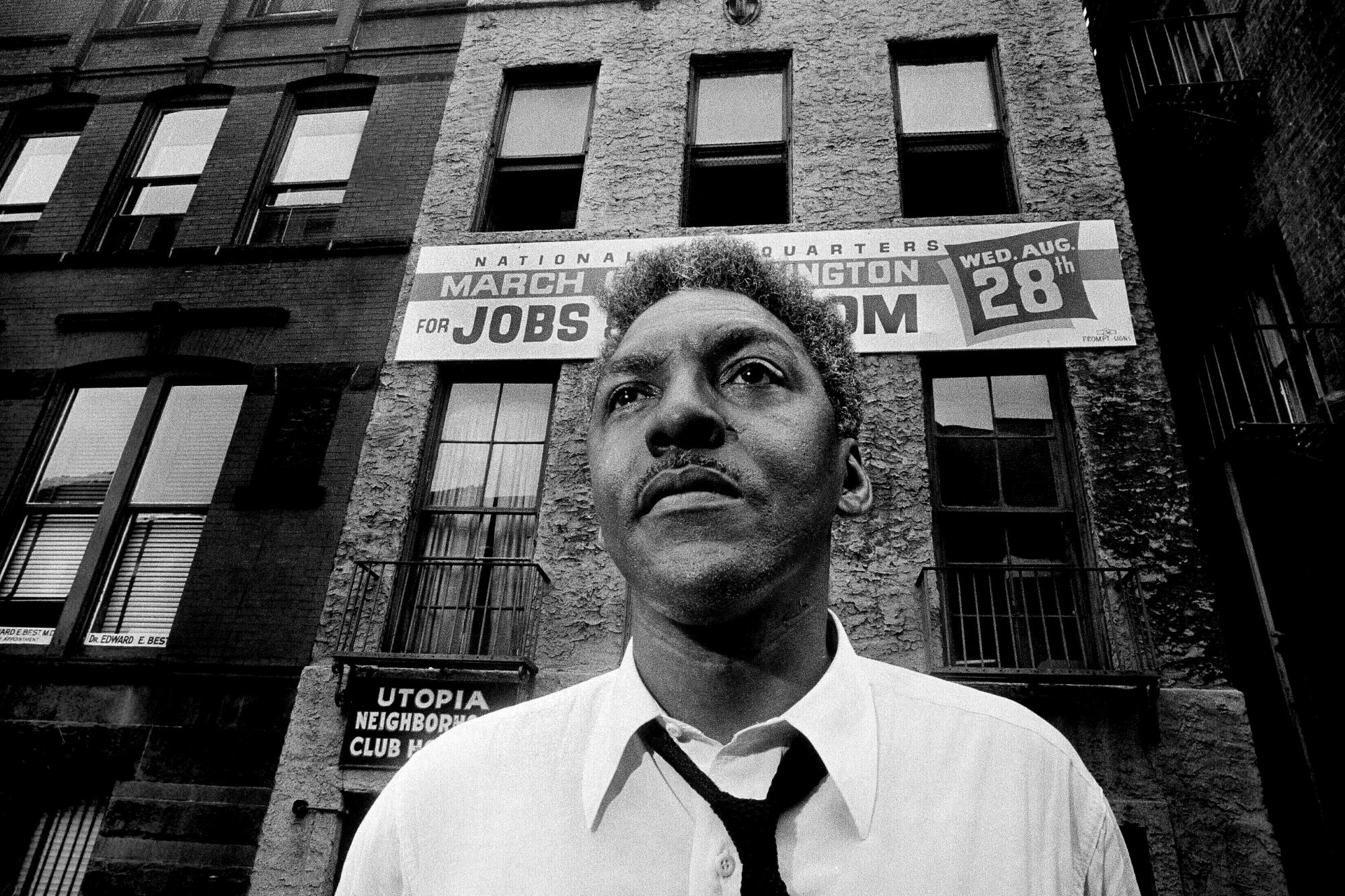

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., a prophet of nonviolence, was deeply influenced by his out gay mentor Bayard Rustin, who convinced him to live by Gandhi’s philosophy. Can their tactics of nonviolent resistance work against a surge in anti-LGBTQ+ hate crimes, laws and propaganda promoted by GOP leaders?

LGBTQ+ resistance hasn’t always been nonviolent. San Francisco’s 1966 Compton’s Cafeteria riot began after a trans woman threw a cup of coffee in a cop’s face, and New York City’s 1969 Stonewall riots became the turning point that triggered a groundswell of national activism.

In the 1970s, the Lavender Panthers, inspired by the Black Panthers, patrolled the streets with knives, chains and shotguns. Later, the activist group Queer Nation helped many feel empowered with the slogan “Queers bash back.”

This tradition of bashing back remains alive today. Last year, during a shooting at a Colorado Springs LGBTQ+ nightclub, it was brute force that stopped the gunman, including a drag performer who stomped him with high heels. Responding with force to persecutors can feel cathartic and, in some situations, necessary.

Engaging with the other side is the only hope for pulling Americans out of the orbit of Marjorie Taylor Greene and her ilk.

But some of the biggest successes in the movement came from nonviolent tactics, such as 1970s campaigns for queer people to come out en masse. Their brave emergence from the shadows revealed to the world that they were family members, friends and neighbors, not predators as they had been called by the authorities. It led the American Psychiatric Assn. to remove homosexuality from its manual of mental illnesses. Crucially, it helped people in the community feel less alone.

The positive impact of queer visibility — in TV shows and on the streets, such as Pride parades and creative protests such as kiss-ins or Act Up’s 1980s die-ins that raised awareness about the AIDS crisis — can’t be overstated.

This tradition of resistance through visibility and nonviolence lives on in public figures such as Lil Nas X, the queer Black singer, and Alok Vaid-Menon, a transfeminine and gender-nonconforming activist and performance artist who responds to attacks on the street and online with radical compassion.

“I need to believe in the humanity of the people who oppress me,” Vaid-Menon told me. Vaid-Menon believes a daily practice of empathy can change the culture of violence, one interaction at a time. “A lot of people think compassion is about letting people off the hook or enabling people,” they said. “Absolutely not. We need to condemn when people get out of line. Compassion is what we do next. How do we believe in other people? I believe that transformation is possible. If I didn’t believe, I wouldn’t be trans.”

If Gen Z Republicans are attacked as bigots, they’re more likely to double down on harmful beliefs, including the idea that they’re victims of oppression.

Vaid-Menon, author of “Beyond the Gender Binary,” performs at comedy clubs and other venues across the world. And in the shows, they speak about the abuse they’ve received all of their life with humor and heartbreaking depth.

After a man punched Vaid-Menon in the face in 2016, they were able to heal from the experience by writing the assailant a love letter. They realized the people who harassed them were asking for help. “They were saying, ‘Look how miserable my life is,’” they said. “I’m just a casualty in the crossfire of their internal world.”

They resist the urge to despise or degrade harassers online and in person because it doesn’t change the cycle of hate. A typical response from Vaid-Menon on Instagram, where they have more than a million followers, reads, “I love you more than you could ever hate me.”

Vaid-Menon explains: “It’s not about sitting back. It’s about being able to look in the eyes of people who do violence and say, ‘I love you. I could be you. And what makes you and I different is not that I’m a better person. It’s that I’ve had people who loved me.’”

There is evidence that Vaid-Menon’s philosophy of radical compassion for haters works. Reporting on radical ideologies, I’ve repeatedly met former extremists who say that compassionate responses and dialogue led them to reevaluate their beliefs.

The election of Donald Trump was a turning point for these young adults, akin to 9/11 for millennials. Gen Zers realized as kids that American exceptionalism was a lie.

Life After Hate, a nonprofit that helps people leave violent far-right groups, says compassion is a major catalyst for de-radicalization. “That is the only way you get extremists to change,” executive director Patrick Riccards told me. And yet, the opposite approach — to demonize, disparage and refuse to enter into dialogue with the perceived “enemy” — is more popular in our digital age, which rewards hostility and aggression with clicks.

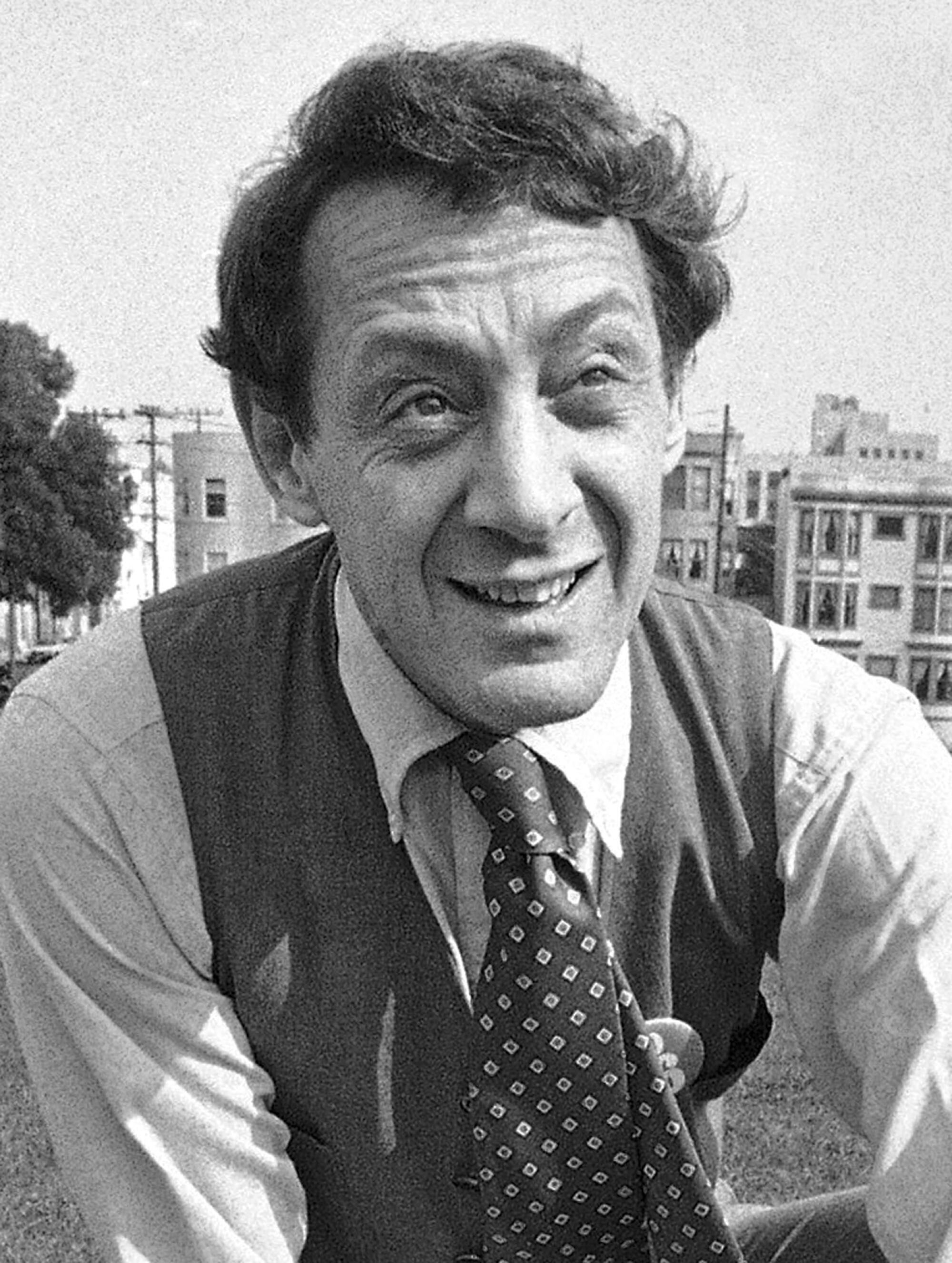

Many activists believe it’s urgent to reverse this course. “I encourage everybody to look for any opportunity to find common ground,” said Cleve Jones, who worked as an intern for Harvey Milk, the San Francisco supervisor and the first out gay man elected to public office in California.

Jones was one of the first people to find Milk’s body after his assassination, and he survived repeated assaults by neo-Nazis. “I’m no stranger to violence,” he told me. “It’s not a hypothetical concept to me. It’s been a part of my life my entire life.”

He said that reaching across the aisle isn’t about avoiding violence. In some cases, it’s the most vulnerable place to be. But it’s necessary. “Do not give into the fear,” Jones said. “If you are frightened, it is even more important to stand up.”

In the district where Carleton was killed for flying a rainbow flag, the Democratic congressional candidate Derek Marshall, who is gay, agrees. He’s among a number of LGBTQ+ candidates running in red districts of California.

He’s been driving Uber 12 hours a day to talk with people in the district, including conservatives, to bridge divides and build relationships. “Both sides need to ask themselves what we can do to turn down the temperature,” he told me.

Many activists are focusing on local and state initiatives because of the divided Congress and right-wing Supreme Court. Tony Hoang, executive director of Equality California, said the organization is providing support for people who are pushing back against anti-gay activism at school board and county supervisor meetings. “We have to reengage at the local level,” he said.

But it shouldn’t be only about playing defense at such meetings. There needs to be proactive measures to support LGBTQ+ rights, such as coordinated efforts to increase the number of states with educational programs on LGBTQ+ issues that can help support queer youths and broaden minds.

“It’s about creating safe spaces and sanctuary jurisdictions, but it’s also about providing positive models,” Marc Stein, a San Francisco State University history professor, said. He noted that historically when policies protective of gay rights were rolled out in the states, they “opened the door to national transformation.”

Activist organizations are doing more to help people in the gay and trans community, including training for reporting hate crimes and programs for preventing bullying or suicide. Some LGBTQ+ leaders, such as Riverside Councilwoman Clarissa Cervantes, believe it’s crucial to create a sense of belonging for everyone, including those who have bought into anti-queer propaganda. “It’s not about us versus them,” she said.

But not everybody feels that way. For some, the sense of fear and us-versus-them is unavoidable. “When you’re gay, you kind of take for granted that people will want to kill you just for walking down the street,” Craig Loftin, an LGBTQ+ historian and American studies lecturer at Cal State Fullerton, told me.

Some trans women are buying weapons and taking martial arts classes. The Pink Pistols, an LGBTQ+ gun rights group, is gaining some traction. One 31-year-old trans woman in San Diego who requested anonymity told me she already bought multiple firearms. She believes in the tradition of nonviolence, but thinks it has limits. “A love letter is not going to stop a 9-millimeter,” she told me.

Allies have a crucial role to play; fighting hate must not fall to the LGBTQ+ community alone. Fly the Pride flag and advocate for LGBTQ+ rights. We can’t go back to the era when gay people had to flee their homes, as some did in the 1970s to try to seek safety in separatist communities in Alpine County and elsewhere.

The war on LGBTQ+ people is also a war on nonviolence. The community has long fought for a world where differences are celebrated, not despised. As Vaid-Menon told me: “It has nothing to do with gender, and everything to do with love.”

Radical compassion may not be a strategy for everyone. But those who embrace this way of dialogue can make a difference. “We need, in every community, a group of angelic troublemakers,” Rustin once said. We should strive to be the people he was talking about.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.