Column: How hip-hop helped me through grief

It’s a strange feeling having your “Day Ones” — the people who believed in you before you believed in yourself — not be around to see how the story is going. I doubt I would have gotten into college without my Aunt Ethel Lee’s support. Sadly, she suffered a stroke my freshman year and wasn’t alive to see me graduate.

By the time I reached 21, “tomorrow isn’t guaranteed” wasn’t something I needed a motivational poster to tell me.

Opinion Columnist

LZ Granderson

LZ Granderson writes about culture, politics, sports and navigating life in America.

My closest friend died from complications of AIDS when I was a sophomore in college. My favorite cousin was shot and killed in Chicago my junior year.

On many days what helped me through that stretch was the classic “They Reminisce Over You (T.R.O.Y.)” on repeat. It was like healing through trauma bonding.

White people shouldn’t just pat themselves on the back for being less terrible than the crowd that attacked a lone Black man on Saturday.

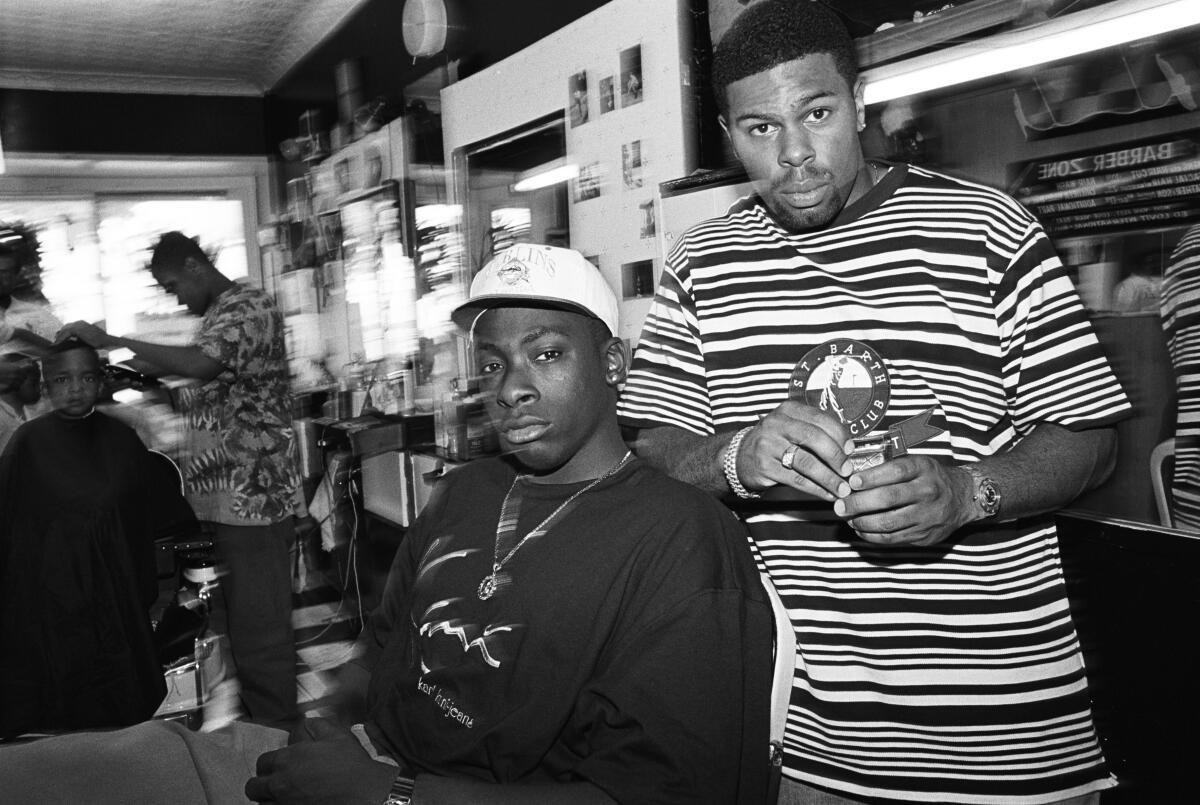

For that 1992 track, Pete Rock and CL Smooth were inspired by the loss of their childhood friend Troy Dixon, who had died in an accident. Dixon was himself a member of the group Heavy D and the Boyz.

“Reminisce” is one of those songs that you don’t so much listen to as experience. The lyrics are as descriptive as a Polaroid; the track reminds me of my auntie’s living room with the plastic on the furniture.

Sure, e-commerce is manipulating me into buying stuff. But if it’s stuff that I want, and it’s at a good price, what’s the problem?

I celebrate hip-hop for being therapeutic for those without the luxury of therapy. Though it wasn’t always easy for that aspect of the culture to cut through the gangsta personification that was driving big business for record labels. In the early 1990s, around the time of the Rodney King assault and the subsequent police officers’ acquittal, the West Coast scene gave us Death Row Records, “Boyz N the Hood,” Snoop, Tupac and the Chronic. Black pain and joy was being expressed, but violence was too often the focus — in the streets and in the C-suites.

When it came to the Billboard charts, the jazz-infused “Reminisce” didn’t leave much of a mark. But that had nothing to do with its power.

Government efforts to silence hip-hop in the ‘80s and ‘90s were just another chapter of white supremacism’s war on truth.

In a 1994 song, when Shaquille O’Neal wanted to honor the father figure in his life, he drew on the last three words of this “Reminisce” passage:

When I date back I recall a man off the family tree

My right hand, Poppa Doc, I see

Took me from a boy to a man so I always had a father

When my biological didn’t bother

Fast forward three decades to the final episode of “Ozark.” As Ruth Langmore drives to her imminent death, “Reminisce” is the last song she hears. That’s one hell of a life span for a song that barely grazed the charts.

Angela Bassett as Queen Ramonda has not been the only Marvel movie performance worthy of industry praise, but it has been the hardest to ignore.

Then again, Black music has never waited for industry permission to matter. Gospel, jazz, the blues, rock ’n’ roll, Motown … why would hip-hop be any different?

Born in 1973, it took six years before hip-hop got a record deal. And that reportedly came because record producer Sylvia Robinson was facing bankruptcy and was willing to take a chance. Crazy that’s how something as influential as the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” came to be. (What’s less shocking is Billboard Magazine crediting a new wave band, Blondie, with having the first No. 1 hit to feature rap vocals — on “Rapture” in 1980. Sadly, that feels very much on brand, for the industry to marginalize Black artists.)

The larger challenge than recruiting officers is maintaining a culture of accountability that builds public trust.

In honoring hip-hop’s 50th anniversary this month, music journalist Naima Cochrane is asking her followers on social media a series of questions about their relationship with the culture. One query sought our pick for the definitive hip-hop track. My choice was easy.

The Tom Scott saxophone sample at the top of “Reminisce” popped in my head before the title. The fact that an obscure six seconds from 1967 could be woven throughout a 1992 track with such craftsmanship that it still registers two decades later is a testament to the song’s overall brilliance.

With all due respect to the club bangers that move the crowd, I’ve always loved hip-hop most when it requires me to be still.

Holds me accountable.

Forces me to acknowledge wounds.

During those times when I think of some of the people who are gone, “Reminisce” remains one of the ways I hold it together. It also lets me fall apart. That’s one of the beautiful things about hip-hop’s longevity. For half a century, it provided a new way for Black men to express creativity and vulnerability.

He has championed guns and gutted mental health care. How can he still claim that access to such care is the key to preventing mass shootings?

Hip-hop covered underreported stories as well.

N.W.A. was more than provocative. The group was sounding an alarm and reporting on an epidemic of police brutality. Judging from this week’s guilty plea by the ex-police officers in Mississippi who called themselves “The Goon Squad,” that alarm is still relevant. As is the emotional storytelling of “Reminisce,” which remains on “best of” lists from Source magazine to Rolling Stone.

Don’t get me wrong. I love a good party. But in those times when hip-hop replaces the bottle in my hand with a mirror, the beat lands differently. That’s because when hip-hop is truly at its best the beat doesn’t hit or drop.

It embraces.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.