Column: The Menendez brothers have been behind bars for 33 years. Is that long enough?

I have not thought much about the Menendez brothers, Lyle and Erik, since they were convicted in 1996 of murdering their parents, Jose and Kitty, in their Beverly Hills mansion.

At the time of the killings, Lyle was 21 and Erik was 18.

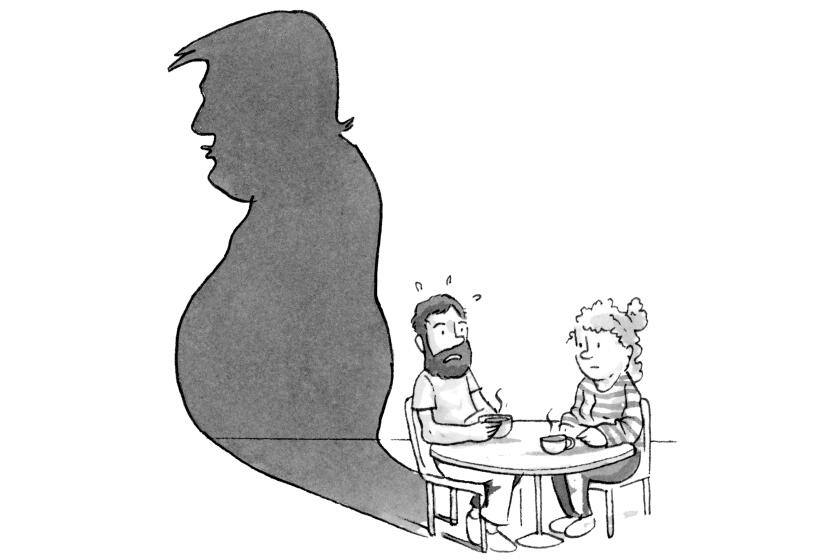

The prosecution contended they were greedy, spoiled brats trying to get their hands on their parents’ fortune. The defense argued that they were severely abused by their father, who was enabled by their mother, and they were in fear for their lives.

The family’s awful story was one chapter of a particularly traumatic era in Los Angeles, where the criminal justice system seemed strained to its limits, where controversies about systemic racism, privilege, domestic violence and fairness raged over the airwaves, at dinner tables and around water coolers.

I would go so far as to say that the 1990s in L.A. essentially began on the August night in 1989 when the Menendez brothers sneaked up on their parents and blew them away with shotguns as the couple watched TV and ate ice cream. Six months later, the brothers, who had managed to spend more than $1 million of their parents’ money in the interim, were under arrest.

A year later, George Holliday videotaped the savage beating of motorist Rodney King by LAPD officers, and the officers’ acquittals sparked days of fires, looting and convulsive violence.

In 1994 — the same year two Menendez juries, one for each young man, deadlocked between manslaughter and murder convictions — Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman were slashed to death in Brentwood. After a volatile trial, Simpson’s ex-husband, O.J. Simpson was acquitted of the slayings in 1995.

The second Menendez trial, this time with one jury, also began in 1995. The same judge who had earlier allowed the defense to call 50 witnesses and present evidence of abuse, restricted testimony that would have supported an “abuse excuse” in the second trial. That sealed the brothers’ fate. They were convicted of first-degree murder in March 1996 and have been in prison for 33 years.

Lyle and Erik Menendez killed their parents, then confessed to a therapist that they were driven by hatred and the desire to be free from their father’s “domination and impossible standards,” prosecutors said as the Beverly Hills brothers went on trial Tuesday for murder.

I would maintain that this convulsive era came to an end the following year, when a civil jury in Santa Monica found Simpson liable for the deaths of his ex-wife and her friend.

I am telling you, it was an emotional and exhausting time in this city. Nothing any of us would want to relive.

But attitudes toward domestic violence and sex abuse have changed. New evidence about the Menendez family has come to light, and now, after resigning themselves to dying in prison, the brothers are hoping the case will be reopened.

A petition filed in Los Angeles County Superior Court in May describes two new pieces of relevant evidence that corroborate Lyle and Erik’s claims that their father was an abusive monster and their mother did nothing to stop him.

One is a letter written by 17-year-old Erik to his cousin discussing his father’s abuse. “I never know when it’s going to happen and it’s driving me crazy,” Erik wrote to his cousin, Andy Cano. “Every night I stay up thinking he might come in.”

Twenty-seven years after Lyle and Erik Menendez were convicted of killing their parents, attorneys say new evidence supports the brothers’ claims that they were sexually abused by their father.

The second is a claim by Roy Rosselló, a former member of the Puerto Rican boy band Menudo, that Jose Menendez, who was chief executive of RCA Records at the time, raped him when he was 13.

A judge has yet to rule on the brothers’ petition, which asks for either an evidentiary hearing or that the convictions and sentences be vacated.

(Rosselló has also alleged that Menudo’s founder, Edgardo Díaz, repeatedly raped him between 1983 and 1986, when he was a member of the group. The LAPD confirmed to my colleague Salvador Hernandez that Díaz is under investigation for an incident that Rosselló says took place at the Biltmore Hotel, where he says Díaz attacked him. Rosselló’s sordid story and Menudo’s connection to Jose Menendez is explored in a powerful new three-part docuseries “Menendez + Menudo: Boys Betrayed” by veteran journalists Robert Rand, author of “The Menendez Murders,” and Nery Ynclan. )

Rand has been writing about the Menendez case since the day after the murders, and has developed close ties with the brothers’ extended family, most of whom believe that Lyle and Erik have served long enough. It was Rand who discovered the letter, written by Erik, that may play a role in reopening the case.

Erik and Lyle Menendez point to a documentary that alleges Jose Menendez sexually assaulted an underage member of Menudo.

“They would have been out a long time ago if they’d had a fair trial,” said Kitty Menendez’s older sister, Joan VanderMolen, 91, who lives in Ventura. In “Menendez + Menudo,” she and her daughter Diane discuss why Erik seemed bereft as a child when there were no lemons in the house. “It was to get the taste of semen out of his mouth,” Joan says, in one of the docuseries’ more shocking moments.

“I loved my sister dearly,” VanderMolen told me last week, “and it’s difficult to talk about her, but somehow she managed to let this husband of hers rule the roost and beat the kids. She had to know.”

She speaks to her nephews regularly by phone at Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility near San Diego, where they were allowed to be together after 22 years apart. “They had a terrible childhood,” she said. “Money had nothing to do with it.”

Who wants to dip back into the malaise of L.A. in the 1990s? Not me. But all these years later, with insights from the #MeToo movement too fresh to ignore and new evidence at hand, reopening the case against Erik and Lyle Menendez seems like the right thing to do.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.