Opinion: I worked with Leslie Van Houten when she was in prison. I’m glad she’s been paroled

Leslie Van Houten was released from prison Tuesday, something I never believed would happen. Not because it shouldn’t, but because it has always seemed to be political suicide to allow it. Part of the notorious Manson “family,” she was serving a life sentence for murdering Leno and Rosemary LaBianca in 1969. She’d been recommended for parole five times before her release. Each time, the recommendation was reversed by either Gov. Jerry Brown or Gov. Gavin Newsom. However, earlier this month Newsom did not challenge an appellate court’s decision to allow parole.

I worked with Leslie for close to 10 years. I taught English at the Chino prison where she was incarcerated through a program at the community college where I work. Leslie was a tutor with whom I worked closely during that time, and she has supported incarcerated women’s education for decades.

I wasn’t sure what to expect when I met her. She was wildly intelligent, kind, soft-spoken and tiny. It was difficult to reconcile the woman in front of me with the crimes she had committed. She has a master’s degree in philosophy and was revered by the women whom she tutored. At prison graduations, cheers recognizing her work were always the loudest.

Legal experts say an exemplary record during Leslie Van Houten’s 53 years in prison made the legal challenges to her release an uphill fight.

During evenings when I’d leave the prison after class, I’d walk through the yard with Leslie and a handful of students, chatting as the sun set. At a certain point, an invisible barrier divided us. I would turn, leaving her behind, walking through the doors upon doors to the exit, driving away to return to the mundane and chaotic world of cellphone notifications, dinner plans, an unraveling marriage, a new career and two small children. Leslie‘s and the other students’ lives seemed suspended while mine was on full blast.

Yet despite the juxtaposition between our lives, Leslie once comforted me during a difficult time. We had been warned against speaking with the incarcerated women about our personal lives, but as she and I sat discussing lesson plans in a prison classroom, it became difficult for me to hide my feelings about my impending divorce. I talked to her about it, my eyes welling with tears. But before I could cry, she told me she’d been married once, too, briefly, and made a joke about it. We laughed and I was grateful for the moment of connection.

Leslie was part of a workshop I led that was part of an exhibit on incarceration curated by our college art museum. Women wrote brief pieces about their experiences of incarceration and recorded themselves reading them in an audio booth someone had donated long ago. Per the prison restrictions, they identified themselves only by the length of their sentence. Leslie recorded a piece about cherishing a visit from her young nephew where they played tag. She wrote about her fear of him asking what she was in for. That was several years ago. I would guess that by now she has told him what she said she planned to say — that she’s a good person who did a bad thing.

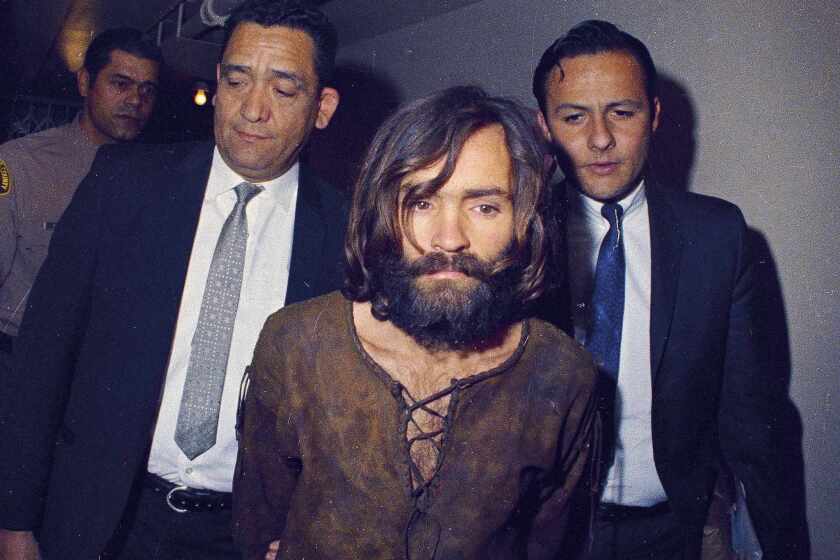

Charles Manson and his “family” committed heinous crimes across Los Angeles in 1969. Here is a timeline of what led up to the murders and the aftermath.

Leslie would mention her hopes of release occasionally and though I supported her, I never imagined it would happen. Per her request, I wrote a letter of support to her parole board. I told them what I saw: Leslie is kind, thoughtful and compassionate. Not only is she not a threat to anyone, she can still do much good in the world. Leslie committed a horrific crime that I don’t excuse. But I also believe we are all capable of more than most of us are willing to admit, even to ourselves. Leslie is a good person who did a bad thing.

Leslie was incarcerated when she was 19. She was released this week as a 73-year-old woman. I wonder how the outside world will unfold for her. I wonder if she will achieve her dream of continuing to teach. I wonder what her relationship with her family will be. I wonder if I will ever see her again. I hope so.

At prison graduation ceremonies, we are prohibited from embracing, so instead we briefly shake hands and we communicate with our eyes emotions that are difficult to put into words. How strange it must be to have human contact regulated for 53 years, for that to suddenly fall away. If I see Leslie again, the first thing I will do is hug her.

Angela Cardinale is a teacher and writer. She teaches English and coordinates online education for a community college in Southern California.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.