After decades of enthusiastically giving Los Angeles tours to out-of-town friends and family, and even co-authoring a walking guide to the city, I’m all too aware that things have changed. Recent guests have been stunned by the tent encampments, sidewalks piled with debris and shuttered storefronts I see daily. I feel embarrassed and heartbroken for the unhoused, their neighbors, my city.

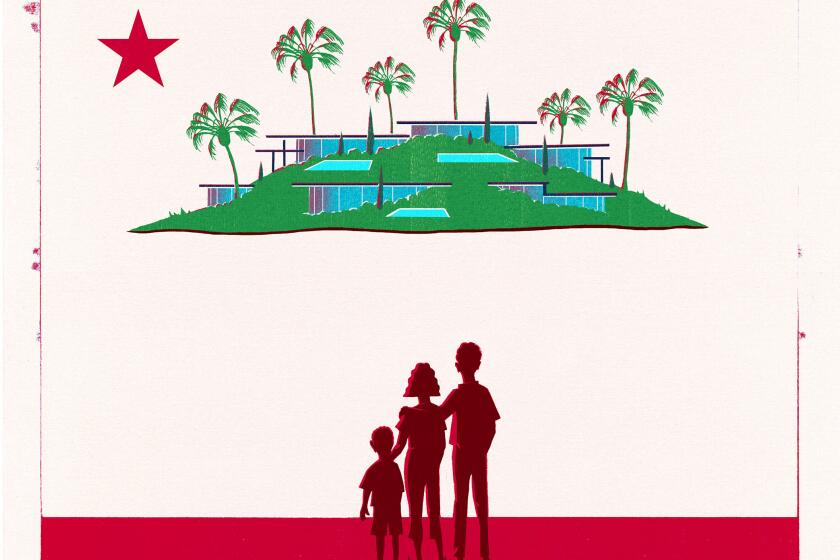

Displaying our problems to visitors has made me think how Los Angeles — even with its history of civil unrest and corruption, poverty and racism, earthquakes and fires — often gets measured against a tradition of cheery propaganda promoting a West Coast paradise. Nineteenth century travel writers likened L.A. to the Holy Land, and the cliché of the California dream persists, despite those who say the promise of abundance and fresh starts is dead, and the dream, a nightmare.

Gov. Gavin Newsom and state leaders like to talk about the sunny myth of California’s promise. But a huge proportion of Californians face staggering economic burdens and very little way out of poverty.

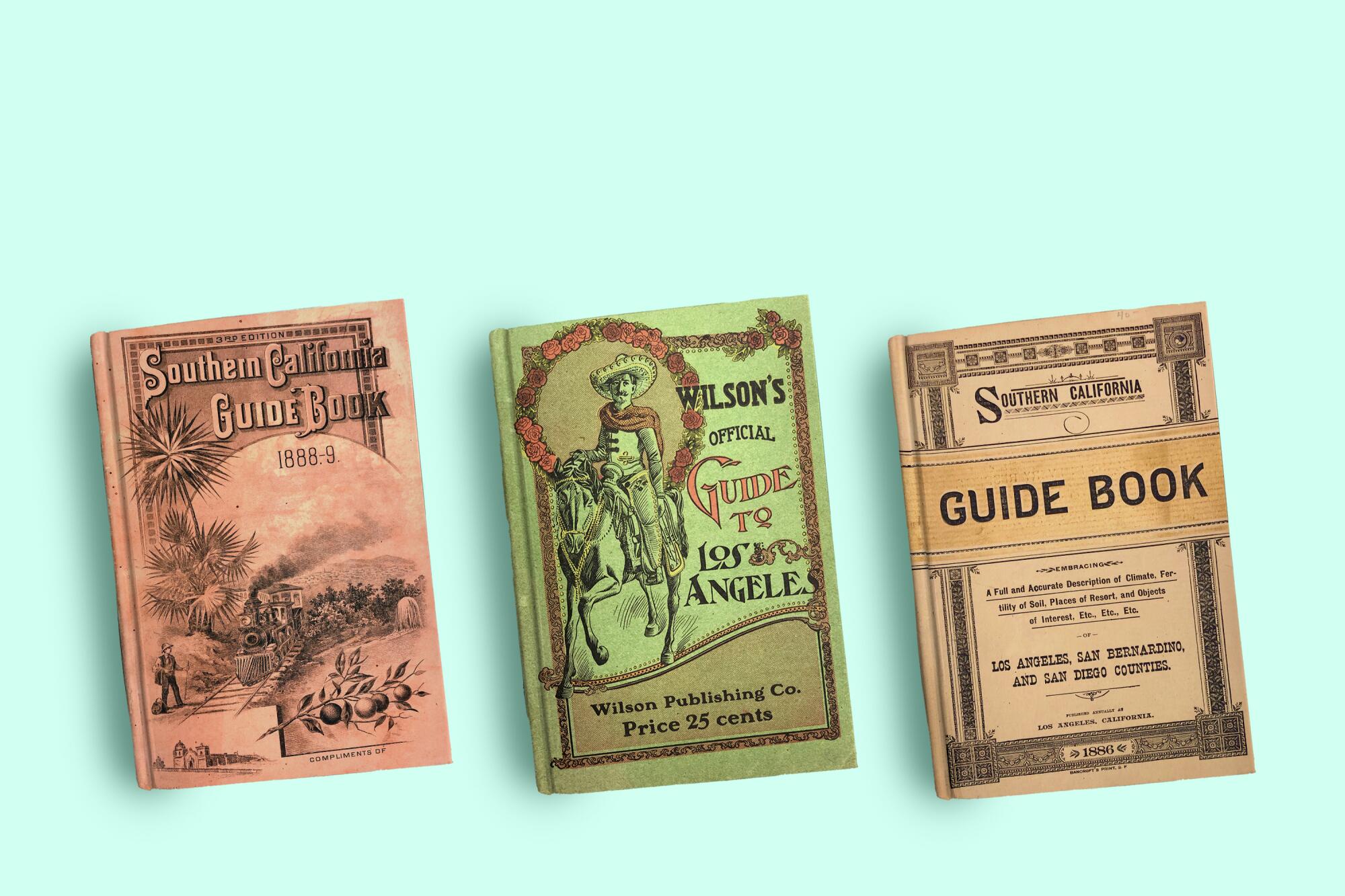

I decided to explore the sources of Los Angeles boosterism and the distance between the “blessed” city and the tent cities we see now. The Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens, in San Marino, graciously gave me status as a “reader” with access to its formidable rare book collection. In California guidebooks dating back to the 19th century, I found the triumphalism, defensiveness and merited pride that’s been baked into Los Angeles’ communal psyche and tourism from the start. I also found prophecies about L.A.’s future success and hints of its enduring failures.

Published in 1885, “The Los Angeles City and County Guidebook for Tourists and Strangers” praises the region for its “unrivaled resources and superb climate” that, it boasts, will cure “innumerable … tormenting ills.” It’s the oldest guide I found in the Huntington’s archives. Besides touting curative weather, it urges visitors to try the first electric elevator in Los Angeles in a four-story downtown office block. And it predicts that pipsqueak Los Angeles — then smaller than San Francisco — would grow in “wealth and population more than any other section in the state.”

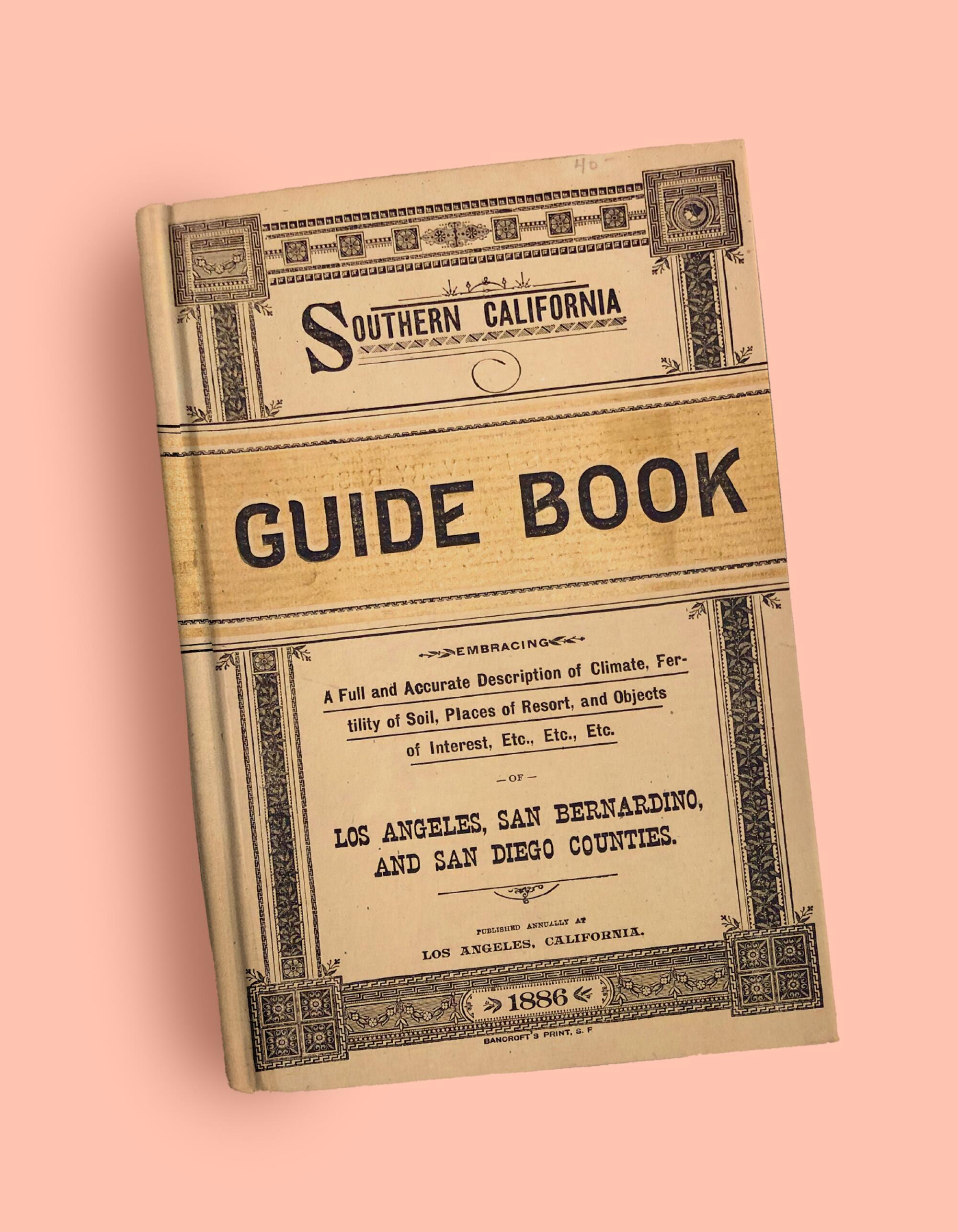

The 1886 “Southern California Guidebook: A Full and Accurate Description of Climate, Fertility of Soil, Place of Resort, and Objects of Interest, Etc. Etc. Etc.” sends tourists to a 700-acre ostrich farm in Los Feliz (adults, 50 cents; children, 25 cents) and to Pasadena’s Raymond Hotel, where “the careworn capitalist can rest and enjoy the warm sunshine in a quiet and elevated place.”

California is losing population and it turns out that among those fleeing to other states, including Texas, Nevada and Arizona, are high-income earners that California relies on for state tax revenue.

It hails L.A. as “one of the most flourishing habitations of man, which has been so highly favored and blessed.” It at least also confesses to “infrequent earthquakes and hailstorms” and professes a little civic humility by way of a humblebrag: L.A. “is not a perfect paradise, nor a heaven on earth, but it is good to be found living here.”

Of course, this kind of puffery was pumped by real estate interests, railroads, newspapers, movie studios and politicians. The painful distance from the truth would fuel satirical novels (since Nathanael West), progressive politics (since Upton Sinclair) and muckraking journalism (since Carey McWilliams).

In “The Bear Book, A Guide to California,” published in 1908 by the California Tourist Bureau in Los Angeles, the climate gets its due again (“not perfect, but none is so nearly so”) and new buildings are praised (“not the finest … but no one of them shrinks from comparison”). “Better come early,” the “Bear Book” smugly advises those interested in relocating, “and avoid disappointment. “

The breathlessness of the guides didn’t surprise me, but the casual racism in some — and the way it revealed the dark side of paradise — did.

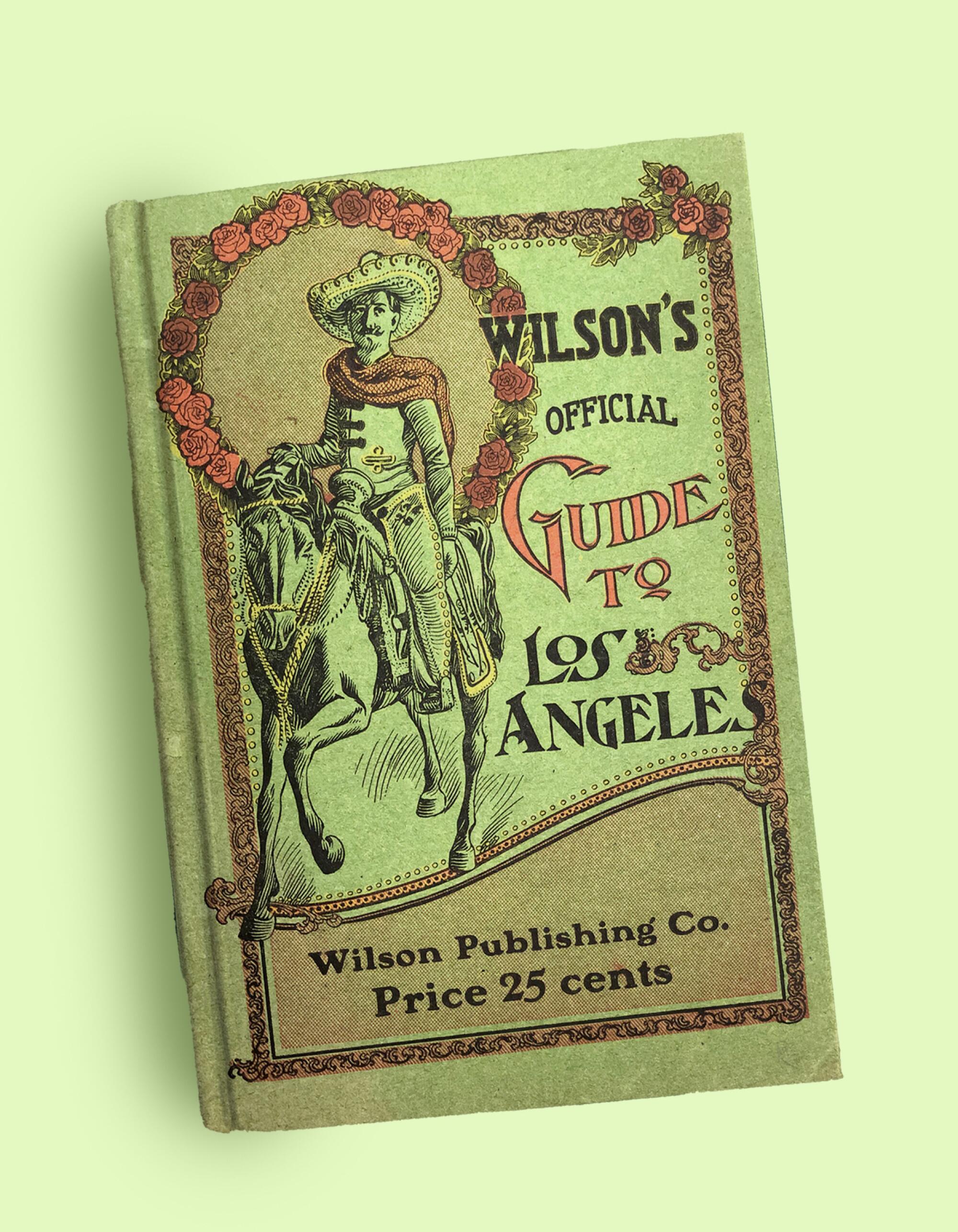

Supposed opium dens of Chinatown are highlighted in “Wilson’s Official Guide to Los Angeles,” 1901 (25 cents). Chinese immigrants, it states, “apparently require less air than other mortals” since they sleep crowded on “shelves in small rooms hardly fit for one.”

The “Tourists’ Guide Book to Southern California,” published in 1894, warns about Chinatown’s dangers: “Especially at night, it is advisable to go in the company of some friend who understands the heathens’ ways or with a policeman.”

The 1885 “City and County Guidebook” assures readers that Mexicans will be pushed from downtown’s plaza where “every square foot … represents a murdered victim.” Mexicans are “being gradually removed by the increase of the value of property,” the book crows. “As the American element is coming in, crime lessens.”

The Depression produced a different kind of guidebook. “Los Angeles in the 1930s: The WPA Guide to the City of Angels” is a 2011 University of California Press repackaging of the 1941 Federal Writers Project volume. In its original preface, Writers Project official John D. Keyes wrote that the goal was to “present Los Angeles truthfully and objectively, neither glorifying it nor vilifying it.” Too often the city “has been lashed as a city of sin and cranks; it also has been strangled beneath a damp blanket of unrestrained eulogy.”

Recent population losses hit rural counties harder than L.A. or the Bay Area and highlight ways we can keep residents in the Golden State.

Today’s readers will be startled by how much in the WPA guidebook has disappeared and how much did not yet exist.

Touted but now vanished: downtown’s glorious 13-story Richfield Building, clad in black terra cotta and gold stripes “symbolizing the black gold of the oil fields,” and the “vast, rambling” Ambassador Hotel (its swimming pool boasted an artificial beach). Tourists might spot movie stars at the Cocoanut Grove, the Brown Derby and Ciro’s (all gone now.)

There was no Music Center, no county Museum of Art, no Dodger Stadium; the first freeway, the Pasadena, was just opening. Yet, with the entertainment industry here, the WPA book foretold that “Los Angeles may well become one of the world’s most influential centers of culture.”

After World War II, skepticism increased. In his 1947 “My L.A.” essays, L.A. Daily News columnist Matt Weinstock startled me with similarities to today’s housing crisis. He describes veterans “living in stores, garages, basements or trailers” and “evicted families sleeping in their cars and single rooms without baths or cooking facilities.”

When America’s favorite Science Guy isn’t teaching people how to save the planet, he rides his bike, eats oysters and contemplates the universe with his wife, Liza Mundy.

His prognosis is cautionary: Los Angeles could end in greatness or “arrogant, militant mediocrity.”

“There is no immediate hope,” Weinstock writes, “that Los Angeles will work itself out of its chaos. There is merely the possibility that with a little luck it will make a pattern of the chaos.”

In recent decades, publication of L.A. guidebooks has mushroomed. Many fixate on movie stars’ graves, rock clubs, surf beaches and food trucks. Some, like the 2021 “People’s Guide to Los Angeles,” another UC Press project, refreshingly tout landmarks of ethnic minorities and labor activism. It documents, for example, the former Black Panther headquarters raided by police and a sweatshop that imprisoned immigrant workers.

Most newer guides in some way still address the allure and the fraying of the California dream, the sense of an original paradise found and lost.

So is it finally time to relinquish the idea that Los Angeles is so special? Or should we hold ourselves and our city to the old ideal, even if it was partly imaginary? Could the “highly favored and blessed” myth prod us to tackle our problems, push us to finally justify the hype?

No guidebook can give us the answers as we compose our future.

Larry Gordon, a native of New Jersey, has lived in Los Angeles for 39 years. He is a former staff writer for the Los Angeles Times and EdSource, and co-author of “Stairway Walks in Los Angeles.”

The California dream has always been a bit of a myth, but so is the notion that it’s coming to an end.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.