Opinion: Harry and Meghan’s car chase claims are alarming. When do paparazzi break the law?

Prince Harry and Meghan Markle, the Duke and Duchess of Sussex, alarmed the world this week by stating that they were “involved in a near-catastrophic car chase at the hands of a ring of highly aggressive paparazzi” in New York City, echoing the deadly pursuit of Princess Diana.

Exactly what happened remains opaque. Photographers at the scene have disputed the couple’s report, saying there were no “near-crashes” and the Sussexes weren’t in any immediate danger.

Nonetheless, the incident raises questions about the laws governing what paparazzi may or may not do.

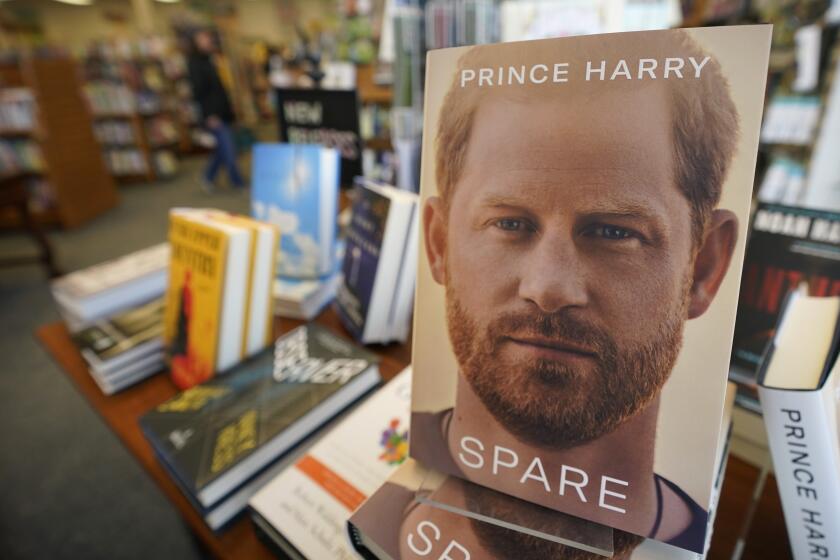

Prince Harry’s memoir, ‘Spare,’ is gracious, harsh, self-pitying, self-deprecating and, ultimately, self-aware.

At one end of the spectrum, paparazzi, like any news media gatherers or members of the public, are perfectly free to capture photographs of celebrities from vantage points open to the public, including the sidewalks of New York. Any celebrity visible in public spaces may be photographed freely.

At the other end of the spectrum, paparazzi, like any news gatherers or members of the public, possess no “get out of jail free” cards when they violate generally applicable criminal or civil laws. The 1st Amendment does not provide a license to trespass on private property or threaten bodily harm in the pursuit of newsworthy photographs or information.

But how does the law draw the line in the intermediate space, in which paparazzi relentlessly swarm and stalk celebrities in public spaces, without engaging in any actual trespass, or overtly threatening physical harm? Surprisingly few judicial decisions have explored this conundrum. Two cases, however, provide useful insights.

In the 1970s, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis was aggressively pursued by photographer Ronald Galella, once dubbed the “godfather of U.S. paparazzi culture.” Onassis sued Galella and won. In litigation battles between the two that extended over decades, courts found that scores of incidents crossed the line from legitimate celebrity news gathering to impermissible harassment. She was riding with son John F. Kennedy Jr. on a bicycle in Central Park when Galella jumped out from behind a bush into the middle of the path, causing John to swerve violently, almost falling off his bicycle.

Gallela hid behind a coat rack in a New York Szechuan restaurant to capture images of Onassis at a private dinner party. When she accompanied daughter Caroline Kennedy to tennis lessons in Central Park, Galella arrived to take photographs from courtside. Galella stalked Onassis by land and sea, even charting boats to capture images of her and her family on the ocean. Onassis alleged that Galella had made her life “intolerable, almost unlivable, with his constant surveillance.” She obtained a court order requiring Galella to keep 25 feet away from her and 30 feet away from her children. The order, which applied only to Galella, was based on his cumulative actions. The precedent, however, could be applied to other paparazzi, including those who doggedly pursue Harry and Meghan.

Another case, in 2012, involved photographer Paul Raef, who was charged with violating a California anti-paparazzi law for allegedly engaging in a high-speed car chase targeting pop singer Justin Bieber. A California trial court initially dismissed the charges, holding that the law targeted the media and thus violated the 1st Amendment. A California appellate court reversed that decision, holding that the California law did not offend the Constitution, because it applied to “any driver who follows too closely, swarms in, or drives recklessly with the requisite intent and purpose, whether or not the driver is a celebrity photographer.”

What lessons can be extracted from these cases? Considered in freeze-frame isolation, any one paparazzi incident may seem innocuous. What’s the big deal over JFK Jr. having to swerve his bike to avoid hitting Galella? What’s so bad about hiding behind a coat rack at a Chinese restaurant? Does Bieber really think it’s so terrible that a photographer follows him in a car? How can Harry and Meghan complain that photographers will do anything and everything to capture images of their everyday life, given their celebrity?

A new series, part of the $100 million Netflix-Sussex deal, launched last week to terrible reviews.

But considered in their cumulative effects, these seemingly trivial slings and arrows of outrageous fortune take on a different dimension. Who among us wouldn’t feel threatened, harassed or intimidated by an apparently orchestrated cabal of photographers engaging in what Harry and Meghan have alleged — run red lights, driving the wrong way down one-way streets, careening onto sidewalks in hot pursuit?

Morally, the allegedly aggressive actions of the paparazzi targeting Harry and Meghan will resonate as particularly reprehensible given the tragic death of Harry’s mother, Diana, which has been widely blamed on the belligerent paparazzi of Paris. Morality and law are not always the same, but as Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes admonished, the law is the “witness and external deposit of our moral life.”

If the tactics of those paparazzi stalking Harry and Meghan crystallize into more than mere moral offense, it could result in legal liability.

Rodney Smolla is president of the Vermont Law and Graduate School and a 1st Amendment scholar and litigator.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.