Opinion: ‘Follow your passion’ is a recipe for being exploited at work

We are often told to “follow our passion,” an idea that has captured the minds of young people, particularly in the last two decades. In pursuing their passion, workers are often willing to go above and beyond, dedicating more time, energy and love to their craft.

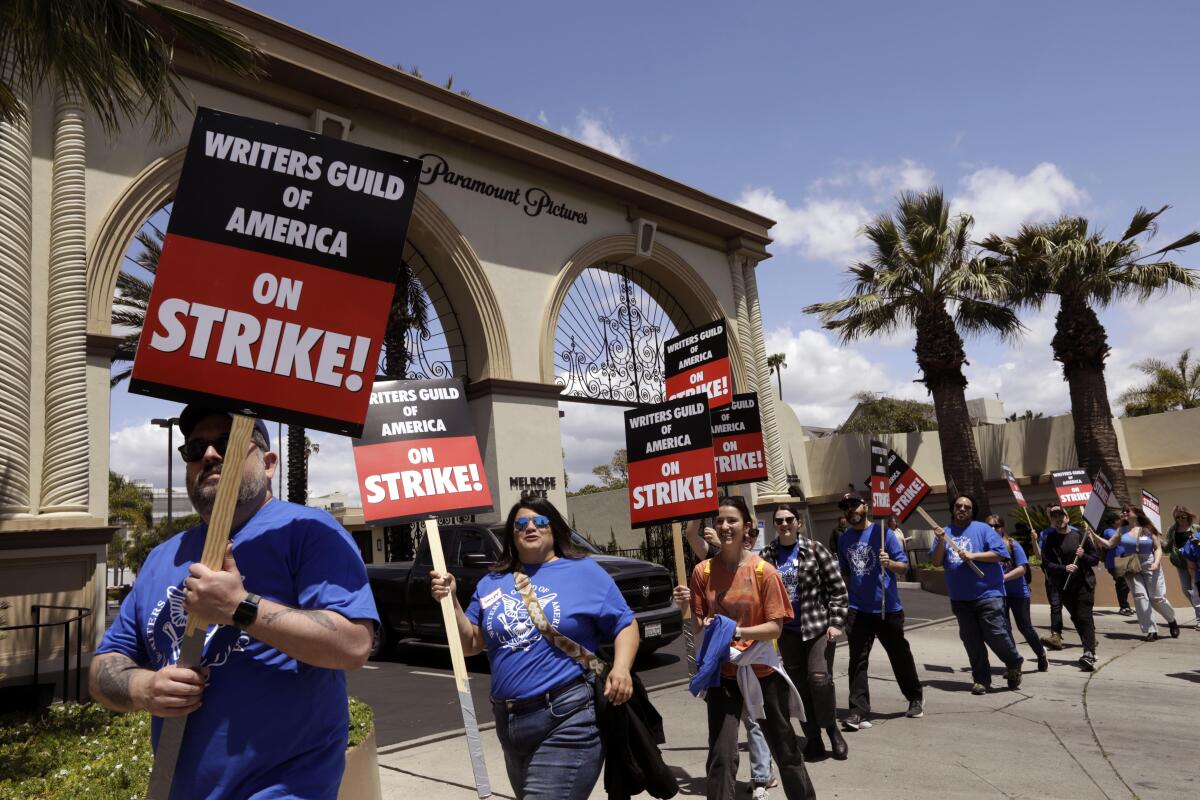

Creative industries like screenwriting are particularly likely to attract passionate workers, commonly expecting employees to work long hours in exchange for the ability to pursue work that satisfies them creatively and intellectually.

During the current Writers Guild of America strike, Warner Bros. Discovery CEO David Zaslav suggested that the strike would end soon because writers have a love for working. After all, shouldn’t work be its own reward for screenwriters who are passionate about their work?

We’ve been grappling with the consequences of machines replacing people for nearly 1,000 years. The idea that automation necessarily creates shared prosperity is an illusion.

But this sentiment is insensitive to the struggles many screenwriters experience — indeed, study after study indicates that passionate workers are often more likely to be exploited by others. We’re apt to be more tolerant of poor working conditions in these professions because we view working for a passion as a luxury.

In turn, fields with the most passionate workers, such as creative industries, healthcare, education, and nonprofit organizations, are also particularly prone to having workers burn out because they care deeply about their work but struggle with the challenging conditions that accompany it. Contrary to the popular belief that “if you do what you love, you never work another day,” it can also be an emotional roller coaster, with high highs, and low lows.

It is not just that passion is an inadequate substitute for poor compensation and long hours, with many writers struggling with financial instability. But poor working conditions may actually impede the potential of passion-driven workers to do better on the job. As the writer Gabriel Sherman notes, “writers need stable income to focus their energy on creative work.” Because investing so much of oneself into a craft with uncertain outcomes can be painful, this kind of work requires more attention and more support, not less.

The last strike cost the local economy $2.1 billion and 37,700 jobs. Los Angeles has an interest in seeing a fast and just resolution in the standoff between writers and the studios.

We should want passionate workers in the writers’ room and elsewhere not because they can be more easily exploited, but because their love of the craft is a vital source of valuable contributions. But when working conditions are poor, this is less likely to happen.

This disconnect between workers and employers is prevalent in other professions that attract people who are driven by a love for their work. In New York, nurses went on strike to call attention to staffing shortages and burnout, and in Scotland, university workers went on strike in a long-running pay dispute.

Of course, inadequate pay and bad workplaces are common in every industry, particularly for low-wage workers. But one difference in passion-driven industries is that workers fear that demanding better treatment makes them seen as less committed to their craft. After all, they’re often told how fortunate they are to be able to do what they love.

But love for the job shouldn’t be used against workers as a substitute for compensation — as if there were some kind of “passion” tax imposed on employees. It should not be viewed as a reason to tolerate bad working conditions, but as a gift that can take work to the next level. This tension may lie at the heart of the WGA strike, and is unlikely to be resolved until the industry recognizes the true value of passion and what workers need.

Jon M. Jachimowicz is an assistant professor at the Harvard Business School. @jonj. Kai Krautter is a research associate at the Harvard Business School. @kkrttr

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.