A few months ago, several members of my family and I took my 88-year-old mother-in-law to Switzerland to help her end her life. At Dignitas, a clinic in Zurich that offers physician-assisted suicide, she drank a dose of pentobarbital, fell asleep almost immediately and minutes later quietly stopped breathing.

Back home, when we had told friends this was about to happen, they were shocked and solicitous. “Oh, my God, her sons must be devastated!” And on a more practical note, “How are you going to spend the two days in Zurich before she dies? Won’t that be unbelievably ghoulish?”

Clearly, these sentiments were well-intentioned, and appreciated. But as it turns out, they were also wrong.

It seems that what unnerved people the most was the idea that my mother-in-law, who had reached the moderate stage of Alzheimer’s disease, was otherwise healthy. Many people support the idea that a person in extreme pain at the end of life should be eligible for help in dying. That’s how the right-to-die laws work in this country. To qualify for a medically induced death, a person must have a terminal illness and already be close to dying (within six months).

But getting help to die when you don’t know that death is in your immediate future?

Even as attitudes toward assisted suicide and euthanasia seem to be loosening, Canada’s liberal laws are causing bioethicists concern.

The concept recently drew attention with the publication of Amy Bloom’s powerful memoir, “In Love: A Memoir of Love and Loss,” about the assisted suicide of her husband, also in Switzerland at Dignitas. Bloom’s focus was on the tragedy of premature loss; her husband had early onset Alzheimer’s, so he was ending his life at the relatively young age of 66. As for my mother-in-law, for years she’d been advocating for the idea that anyone — or at least anyone with a compelling physical or mental medical reason — should have the right to end their life on their own terms.

She had always, and often, told family and friends that when she could no longer do the things that gave her pleasure and made her her, she would no longer find life worthwhile. She was an intellectual who loved to read and have lively conversations. Every day of her life she took long walks while listening to classical music. She was a devoted follower of Democratic politics. And she loved spending time with her three sons and their families.

Still, she had no interest in living forever, and as the things she loved became too difficult for her, she became more and more committed to the Dignitas option. And her family was supportive of the decision. Of course we’re sad and will miss her terribly. But it was what she wanted, and it allowed her to avoid the years of misery that usually attend Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia. Also, along with the many pleasures she had had in her life, there had been many disappointments. Ending her life when and how she wanted to was something she felt very strongly about, and we were pleased for her — proud, even — that she was able to achieve that.

Long before she got her terminal cancer diagnosis, Gabriella Walsh had considered the situation as a hypothetical: If her time was limited, she didn’t want to prolong her life. Her priority was the quality of the days that remained.

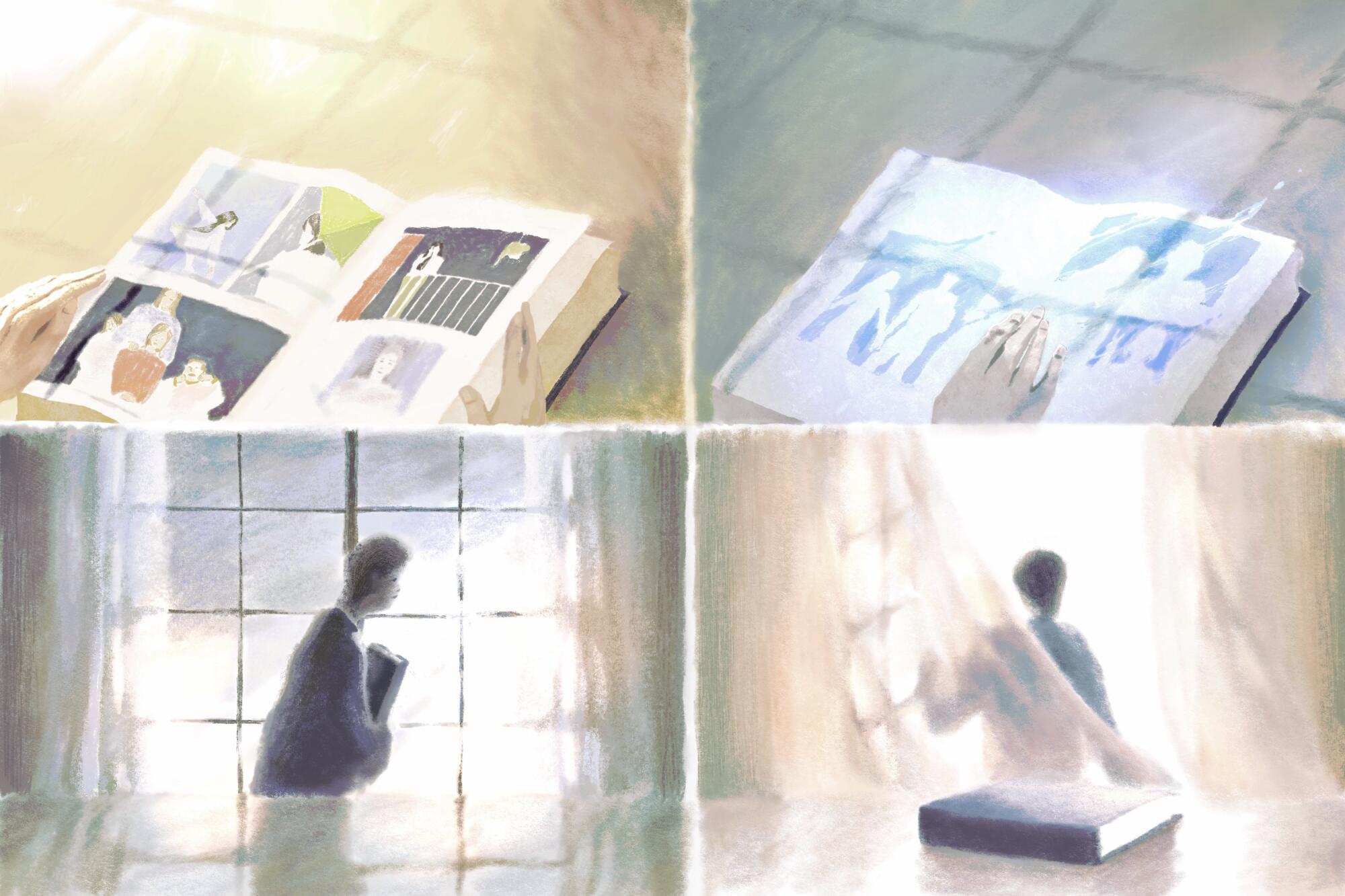

I wish I could adequately describe the lovely final days we all spent together — my mother-in-law, my husband, his two brothers, and one of my nieces. We stayed in an Airbnb in Zurich and had a pretty ordinary few days: taking walks, eating meals together, reminiscing and looking at old family pictures.

Despite the underlying sadness, it wasn’t a particularly emotional time. My mother-in-law seemed to be encased in some kind of protective cone that allowed her to enjoy her last days without focusing on what was about to happen. She never panicked or evinced any second thoughts; nor did she seem driven to have any kind of intense goodbyes with individual members of the family. None of us cried (that came later).

Once we got past the euphemism stage of what was about to happen, we even started making jokes about it, which she enjoyed immensely. She had received many loving emails from family and friends who knew about her plans, and we told her how lucky she was to be able to enjoy her memorial before her death. We teased her about how we’d try to let her know somehow if Donald Trump ever got indicted. We even laughed about the fact that once we all arrived in Zurich, hers was the only luggage that didn’t make it. (Believe it or not, it finally showed up the day she died.)

All things considered, my mother-in-law had a much more pleasant sendoff than most.

As for the bigger picture of what her death meant, I can say only that I wish more people who suffer mentally in this country had a similar option. It doesn’t seem right that a person with six months to live can get help ending their life but someone facing years of mental anguish cannot.

‘Death with dignity’ laws make assisted suicide possible in the U.S., but those laws don’t apply if you’re suffering from Alzheimer’s.

Of course, there is much potential for abuse. We were fortunate that my mother-in-law’s circumstances lined up just right: her age, the family support, and that we were able to afford the $12,000 cost, plus the trip to Zurich.

It’s easy to imagine the slippery slope, people pressuring someone to die for any number of reasons: “Mom’s about to run out of money, and we don’t have the wherewithal to care for someone with advanced dementia.” Also, where do you draw the line on whom to accept for an assisted death? Should someone who is clinically depressed be eligible? Or a person who just feels tired of life?

Clearly, physician-assisted suicide is a difficult minefield to negotiate, which no doubt explains why it’s so rare, and so heavily restricted in this country. Only 10 states plus the District of Columbia allow it. In California, population 39 million, fewer than 500 people use it to end their lives annually.

But just because assisted death is complicated to regulate doesn’t mean it’s impossible. That’s for the medical ethics people and state legislatures to work out.

What I know is that after my family’s experience with Dignitas, we will cherish the right my mother-in-law exercised, whether or not we ever choose to do the same.

Nan Wiener is a freelance book editor in San Francisco.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.