Editorial: The Supreme Court needs ethics reform. That shouldn’t be a partisan issue

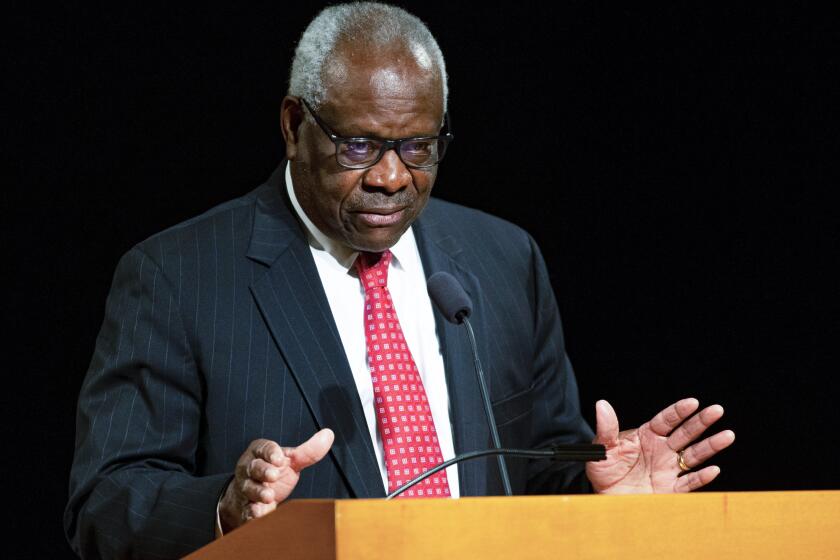

Thanks to recent reports about financial and personal dealings by members of the Supreme Court — including lavish trips bestowed upon Justice Clarence Thomas by a friend and prominent Republican donor — the public has become aware of a troubling fact: Unlike other federal judges, justices aren’t bound by the Code of Conduct for United States Judges. But if that loophole is to be closed by Congress, bipartisan support will be necessary.

That will be difficult because, as a hearing Tuesday by the Senate Judiciary Committee demonstrated, the campaign to tighten ethics for the high court is ensnarled by partisan divisions in Congress. The leading proponents of ethics reform are Democrats, while Republicans are reflexively defending the court. Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, the panel’s ranking Republican, railed against an “unseemly effort” to undermine the high court’s legitimacy.

Reform of the court shouldn’t be a partisan issue. Fortunately, there is now an effort co-sponsored by a Republican senator, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, and an independent senator, Angus King of Maine, who caucuses with Democrats. It could be refined, but its introduction is a milestone.

Fixed terms would lower the political temperature of Supreme Court appointments

Though less ambitious than other proposals, the Supreme Court Code of Conduct Act comprises important reforms: a code of conduct for the justices, which the court itself would issue, and a mechanism for the investigation of whether a justice engaged in conduct prejudicial to the administration of justice or in violation of federal law or codes of conduct. The bill also would require the court to designate an individual to process complaints against justices.

Under existing law, complaints can be filed alleging that lower-court federal judges engaged in “conduct prejudicial to the effective and expeditious administration of the business of the courts” or are “unable to discharge their duties by reason of mental or physical disability.”

There ought to be a similar process for filing complaints about ethical lapses by Supreme Court justices, though because of their prominence justices might be targets of frivolous or politically motivated complaints. Ideally, justices — and other federal judges — also should be required to seek approval in advance before accepting gifts or travel and lodging.

How hard could it be for Clarence Thomas, the longest-serving Supreme Court justice, to figure out how to follow financial disclosure law?

So far the justices’ attitude to criticism seems to be “nothing to see here.” In declining a request to testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. cited a statement agreed to by all current members of the court. The statement noted that in 1991 justices voluntarily adopted a resolution to follow the substance of the regulations of the Judicial Conference of the United States. Since then, it added, “justices have followed the financial disclosure requirements and limitations on gifts, outside earned income, outside employment, and honoraria. They file the same annual financial disclosure reports as other federal judges.”

That may sound reassuring, but the justices still aren’t bound by the code of conduct applicable to other federal judges. Thomas didn’t reveal the lavish hospitality he received from real estate developer Harlan Crow in his voluntarily disclosures. After Pro Publica reported on that generosity, Thomas said that he had received advice from colleagues and others in the judiciary that “personal hospitality from close personal friends, who did not have business before the court, was not reportable.”

Thomas added that he would comply with new and more stringent disclosure guidance promulgated earlier this year by the Judicial Conference. (Of course, sometimes disclosure won’t be enough to inspire public confidence. Justices should decline generous gifts from political actors, even if they are friends.)

Even if the Supreme Court were to adopt a code of conduct, it wouldn’t rectify all of the court’s credibility problems. The justices have lost public confidence not wholly, or even primarily, because of perceived ethical lapses. The court’s image also suffers because of the perception that the justices are predictable partisans in politically charged cases and the successful effort by Republicans to cement a conservative majority on the court by blocking a superbly qualified nominee, Merrick Garland, who was nominated by then-President Obama in 2016. The culmination of that strategy was last year’s disastrous decision overruling Roe vs. Wade and extinguishing a federal constitutional right to abortion.

But ethics reform is still important. In an injudicious interview published in the Wall Street Journal, Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. — the author of the majority opinion overruling Roe — said that it wasn’t surprising that the court’s approval rating was sagging with critics saying “day in and day out, ‘They’re illegitimate. They’re engaging in all sorts of unethical conduct.’ “ A binding code of conduct for the court is one way to address such criticism.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.