Editorial: The new anti-trash mantra should be reduce, recycle — and repair

One of the most pernicious sources of plastic waste will never be welcome in our blue recycling bins because, well, they are supposed to last.

But the truth is that while so-called durable goods, from kitchen spatulas to flat-screen televisions, have a longer shelf life than their single-use brethren, many don’t last more than a few years before they break. And at that point, there are few options but to toss them into one of the ever-growing piles of plastic trash that taint the Earth’s surface.

These products often contain parts made from other material, but plastic is typically a significant component. So when old vacuums and coffee makers die, their plastic parts don’t biodegrade, they break down into smaller and smaller pieces — until the microscopic particles find their ways into the food we eat, the water we drink and the air we breathe.

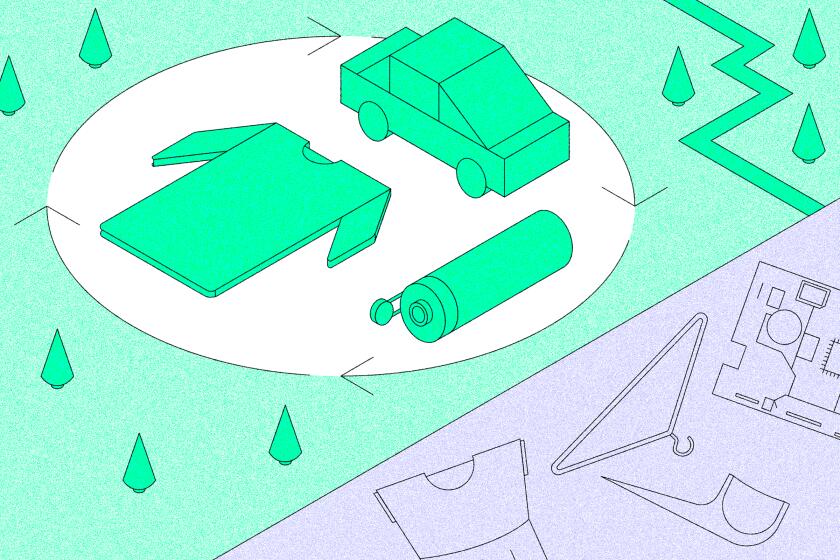

This is our chance to develop a circular economy: a system in which every product, building, vehicle, thing is designed to have a long and useful afterlife.

Retooling the residential recycling system to accommodate a million different plastic household products is not a solution to this waste problem. No, the best way to reduce this source of plastic is to consume less of it.

Fortunately, there’s an easy fix that doesn’t involve shutting down Amazon, ushering in higher inflation or banning anything. In fact, it could save consumers time and money, while encouraging the growth of local businesses. It’s called right to repair, and there’s a bill in Sacramento that could turn this policy into reality in California.

You may be wondering why you need a law to ensure you can fix the things you own. As consumer products have become more digital, manufacturers have used technology to make it difficult, if not impossible, for consumers to repair malfunctioning appliances and electronics themselves or with a local fix-it shop. Instead, consumers are often required to schlep to one of a few authorized repair shops, which may charge prohibitively high repair fees, or mail the product back to the manufacturer. In the end, it’s easier and often cheaper to buy a replacement TV, smartphone or desktop printer. It’s more profitable for manufacturers too to sell new versions every couple of years, rather than just a few parts to fix the older models.

Right-to-repair laws, which have popped up around the country in recent years, require product manufacturers to provide consumers and independent repair shops reasonable access to repair manuals, parts and software so they have more options when products break.

Consumers should have the authority and tools to fix the stuff they own. But they don’t if those things have digital components

The U.S. Public Interest Research Group, one of the main consumer groups behind right-to-repair laws, estimates that consumers could save as much as $40 billion every year if they were able to extend the useful lives of electronics and appliances by 50%.

Last year, New York became the first state to pass a right-to-repair law for electronic devices. California could be the second this year if the Legislature passes Senate Bill 244 by Sen. Susan Talamantes Eggman (D-Stockton) — a sweeping proposal that would include most consumer electronics and appliances. That is, if it gets through its next hurdle in the Senate Appropriations Committee, where two right-to-repair bills have stalled in the last two years without explanation from its chairman, Sen. Anthony Portantino (D-Burbank).

Perhaps Portantino was influenced by the tech and manufacturing industries that argue giving consumers more repair options threatens product safety and intellectual property rights, and risks customer data privacy.

It’s a lot of hot air, according to the Federal Trade Commission. FTC attorney Dan Salsburg testified in support of SB 244 before the state Senate Judiciary Committee last month, noting that the agency looked into the industry’s claims and found no evidence that independent fix-it businesses are more likely to misuse customer data than authorized shops.

What product makers don’t want is consumers having more control about how and where to get the things they own repaired. It’s no surprise that right-to-repair laws are strongly supported by Americans across the political spectrum. Save money and support local businesses? What’s not to love?

The time has come for California lawmakers (looking at you, Sen. Portantino) to stand in support of this important anti-waste effort.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.