Column: Donald Trump is headed to court. That should be the last place he wants to be

Donald Trump announced in an interview aired this week that he is prepared to run for president even if he is convicted of a crime. He’d better be, because his candidacy is doing nothing to decrease his enormous legal exposure.

In the face of risks grave enough to alarm even the most reckless litigant, Trump has adopted an attitude of imperious derision. The goal, if you can ascribe a goal to anyone as reactive as the former president, seems to be to turn public and political opinion against his antagonists.

But even if Trump retains his ability to rev up rallies and call on slavish allies in Congress, neither public opinion nor so-called legislative oversight can protect him from the legal perils arrayed against him. The defenses he is offering in public are unlikely to fly in the courts, which is where he will need them. Indeed, the rules and dictates of the courtroom may well prevent his ever making much of his case inside one.

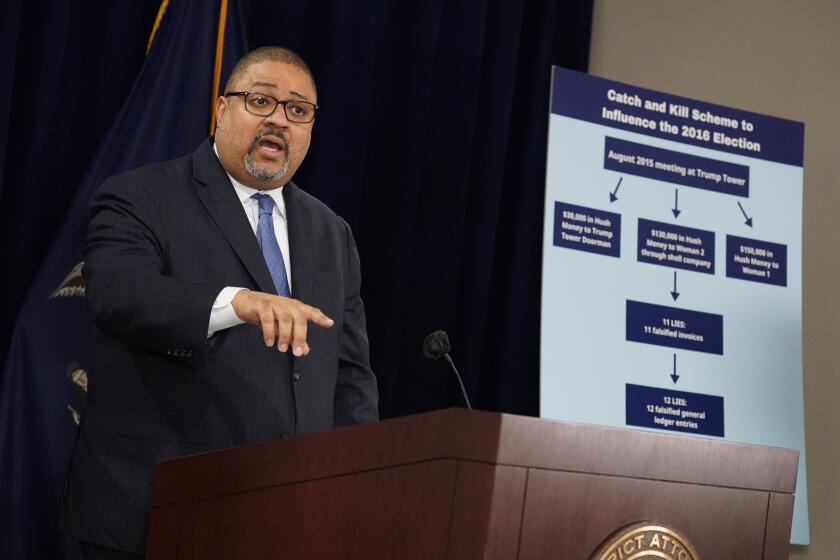

The Manhattan district attorney pointed to new evidence that the payment to Stormy Daniels was meant to break campaign finance and even tax law.

Start with Trump’s transparently racist attacks on Manhattan Dist. Atty. Alvin Bragg and the accusation, echoed by Ohio Rep. Jim Jordan and company, that the ex-president was indicted “for no crime” but rather for political reasons. Since it’s manifest that the district attorney’s office regularly brings similar charges against others, Trump’s team can’t begin to make the required showing for such arguments in court.

Trump’s purported factual defenses against Bragg’s case, being offered bombastically at campaign rallies, are that he never had sex with Stormy Daniels and that the payout to her was meant to spare his family from a revelation of her accusations — not, as prosecutors are expected to argue, to illegally bolster his 2016 campaign. These arguments face even greater obstacles to ever being heard in court.

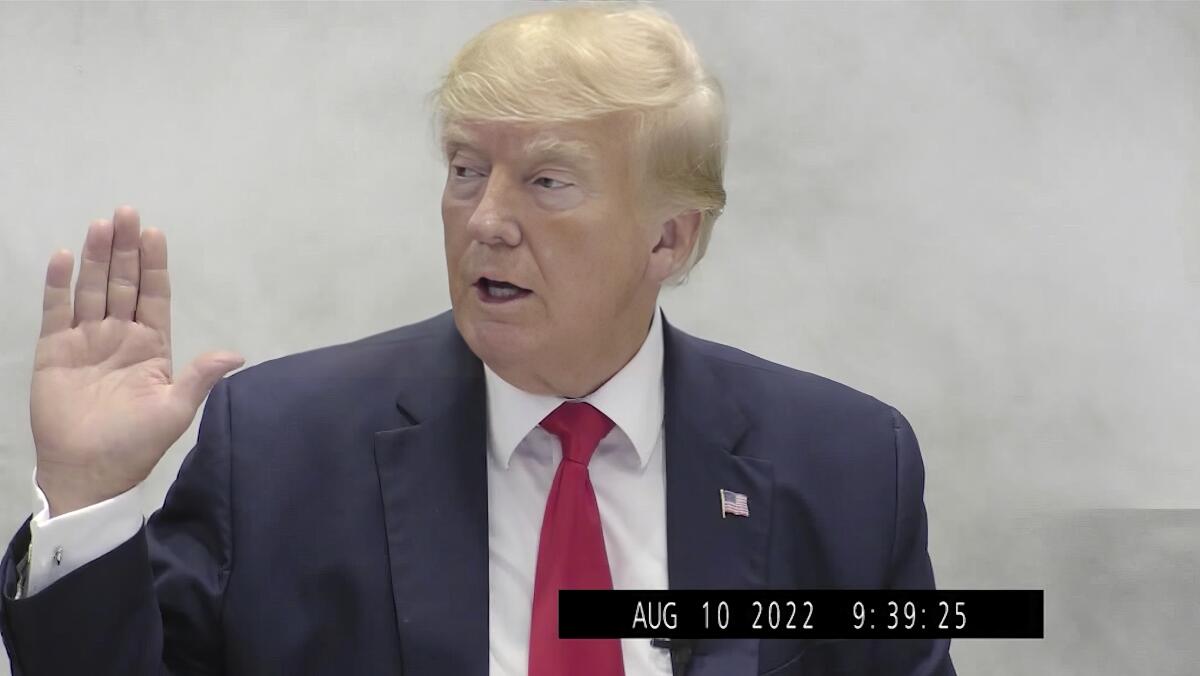

Trials are carried out under rules of evidence designed to ensure that testimony is reliable and relevant — the opposite of Trump’s typical approach on the stump. How can he persuade a jury of reasonable doubt about the charges under those rules? The most obvious and perhaps the only way would be to take the stand to testify in his own defense.

But the first axiom of any trial involving Trump is that he cannot testify. There isn’t a respectable lawyer in the country who would put him on the stand.

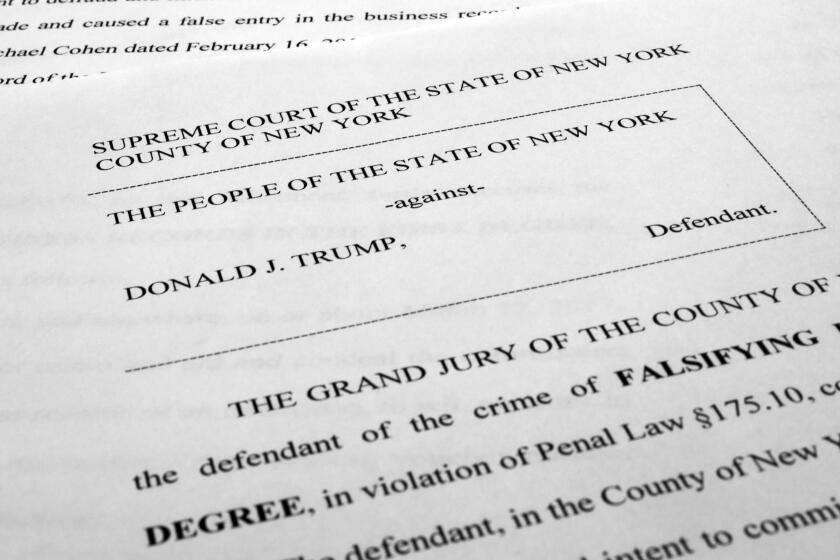

Former President Trump appeared in New York and his indictment was unsealed. The charges involve his payment of hush money to Stormy Daniels.

Under the rules of evidence, taking the stand would put Trump’s credibility at issue, permitting the prosecution to confront him with lies he has told. The Washington Post has documented over 30,000 from his presidency alone, many of them flagrant and undeniable.

The procedures for cross-examination would leave Trump no room to dodge questions or grandstand. A skilled lawyer would be able to bring him to heel and force him to answer yes or no — in his case, to admit the truth or commit perjury. The result would be a humiliating new low for the defendant.

Even before Bragg’s case proceeds, Trump faces the same conundrum in E. Jean Carroll’s lawsuit, which is scheduled to go to trial next week (though Trump moved Tuesday to postpone it because of the publicity surrounding the Bragg indictment). To offer the defense that he never assaulted Carroll, whom he has said was “not [his] type,” he would have to take the stand.

It will not happen. He can’t afford to appear in a setting where he has to tell the truth.

The rules also stand in the way of Trump’s having other people testify that he told them, for example, that the Daniels payout was to protect Melania’s feelings. Under the rules of evidence, such testimony would be inadmissible as hearsay, considered unreliable because the person who made the statement wouldn’t be making himself available for cross-examination. (Trump could try a couple of strategies to get in hearsay statements, but they would be of little help because the rules would permit the prosecution to cast doubt on his credibility as if he had taken the stand.)

The same rules, however, specifically permit such statements by prosecution witnesses. So while Trump can’t offer evidence of a self-serving statement through a third party, Bragg can introduce evidence of virtually every statement the former president has made.

For example, likely prosecution witness David Pecker, the former chief executive of the National Enquirer’s parent company, could testify that Trump told him he wanted to “catch and kill” potentially damaging stories for political reasons. Trump’s lawyers could try to impeach Pecker’s credibility, but they couldn’t, say, put Jim Jordan on the stand to testify that Trump told him he did it for Melania. Only Trump could testify to that. (See Axiom 1.)

Trump’s instinctive slash-and-burn approach has carried him through a lifetime of consequence-dodging. He has always been able to make his own rules, but he won’t be able to do that in the consequential arena he is entering. The justice system operates by its own rules, and they are deeply unfavorable to him.

Harry Litman is the host of the “Talking Feds” podcast. @harrylitman

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.