Editorial: Ambassador Garcetti breaks the curse on L.A. mayors’ political ambitions

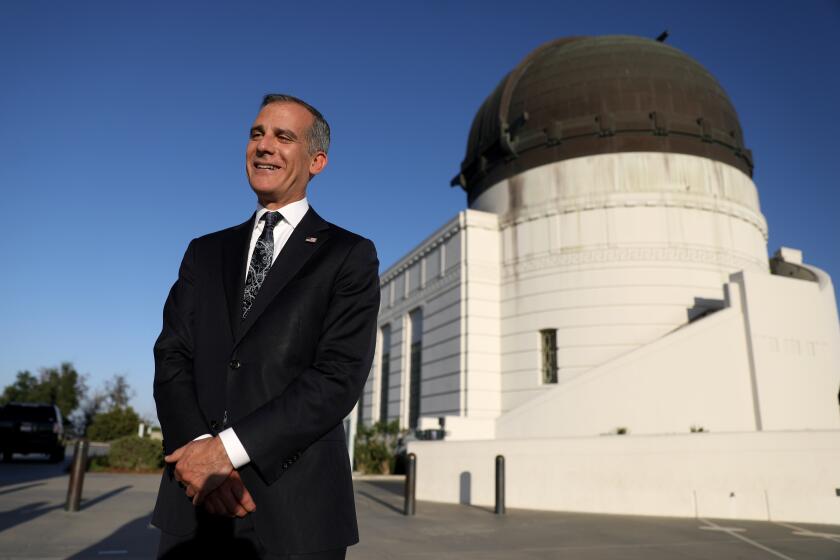

Congratulations to Eric Garcetti, and not just for becoming the U.S. ambassador to India.

For decades, the job of mayor of L.A. has been a dead end, politically speaking. By finally snagging himself a plum appointment, Garcetti has bucked history and may have broken the curse that has long plagued past mayors’ political ambitions.

On Wednesday, the U.S. Senate voted to confirm Garcetti’s nomination. But the closeness of the final vote — 52 to 42, in a chamber controlled by Democrats — means the shadow over Garcetti hasn’t gone away.

He’d be a good ambassador to India. But Los Angeles is better off if he spends his last year in office ambitiously, relentlessly carrying out his policy agenda.

Garcetti, who was an early supporter of Joe Biden’s presidential campaign, was first nominated for the post in July 2021. A former Rhodes scholar who taught international relations and diplomacy before running for office, he seemed like a shoo-in for the post. But the nomination process dragged on, partly for partisan political reasons but also because of serious questions over whether the mayor tolerated sexual harassment and bullying by one of his closest aides.

The mayor’s bodyguard, Matthew Garza, sued the city in 2020, alleging he was repeatedly sexually harassed by Garcetti’s advisor, Rick Jacobs — often in front of Garcetti. (The lawsuit is scheduled to go to trial in September.)

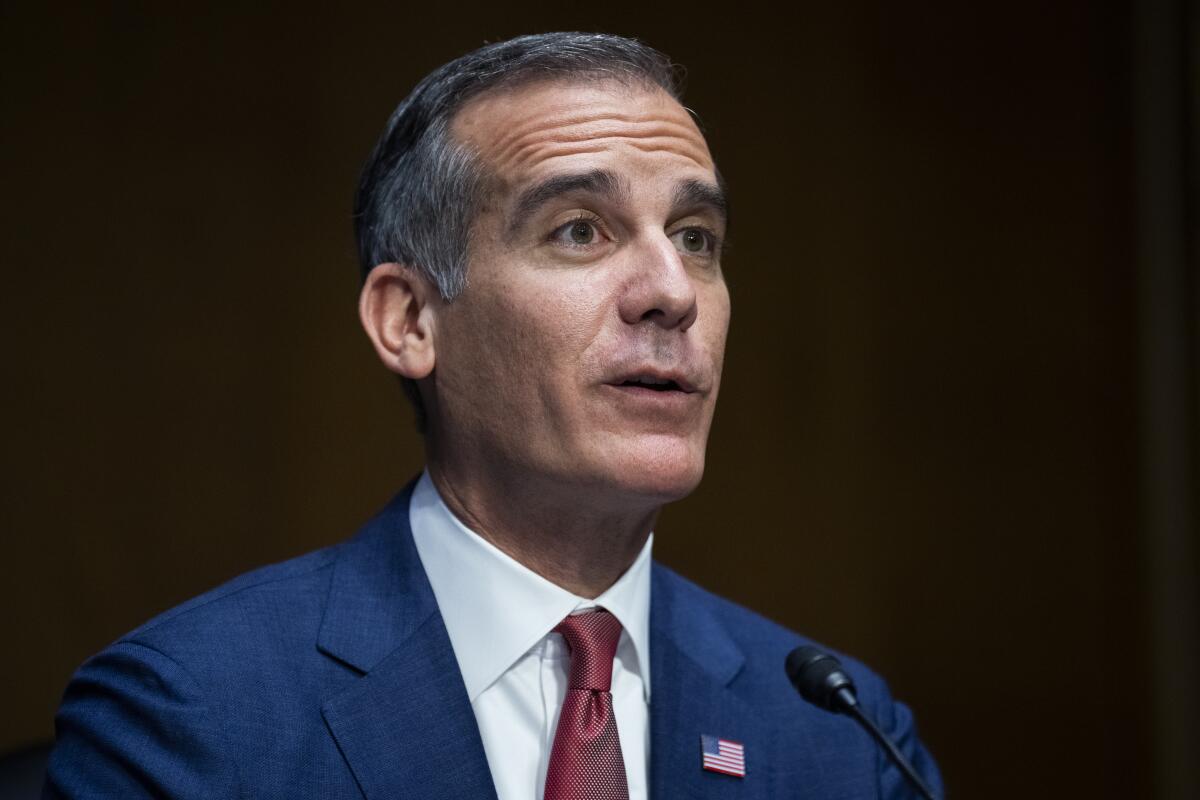

Garcetti testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that he never witnessed misconduct by Jacobs and, if he had, he would have stopped it. After former Garcetti employees went to Sen. Charles E. Grassley (R-Iowa) to raise red flags on the nomination, the senator ordered a report that concluded Garcetti “likely knew or should have known” about Jacob’s conduct. Around that time, Garcetti’s parents hired a lobbying firm to help press his case in Washington.

Reports about nasty messages in a private Facebook group are part of a pattern of behavior at City Hall that reflects poorly on Mayor Eric Garcetti.

In the end, three Democratic senators — Mazie Hirono of Hawaii, Sherrod Brown of Ohio and Mark Kelly of Arizona — voted against Garcetti, saying they had serious concerns based on what they’d heard. He was saved by several Republican senators who supported his appointment, in part so the U.S. would finally have an ambassador to a key strategic ally.

Unlike mayors before him, Garcetti now gets a new chapter in his political career. Tom Bradley, Richard Riordan and Antonio Villaraigosa all ran for governor and lost. Sam Yorty, who was a perennial seeker of higher office, ran for president in the 1972 Democratic primary and lost. Garcetti spent nearly two years exploring a presidential run but announced in 2019 that he would focus on being mayor instead.

Maybe the best strategy is to seek the mayor’s job at the end of a long career, like Karen Bass did. During her campaign last year, she was seen as a politician running for her last job and willing to take on the politically unrewarding work of trying to solve L.A.’s homelessness crisis.

In the best of times, the job of running Los Angeles is incredibly difficult, demanding and often thankless. It’s a sprawling city that, historically, hasn’t had a strong culture of political engagement. The mayor, one of few recognizable political figures in the region, gets to lead the celebration for big wins (even when they’re not technically in the city) and is blamed when things go wrong (even when the mayor isn’t the only politician responsible). Perhaps the curse of the office as a career ender is useful in weeding out would-be candidates for mayor who are more interested in their future than the city’s.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.