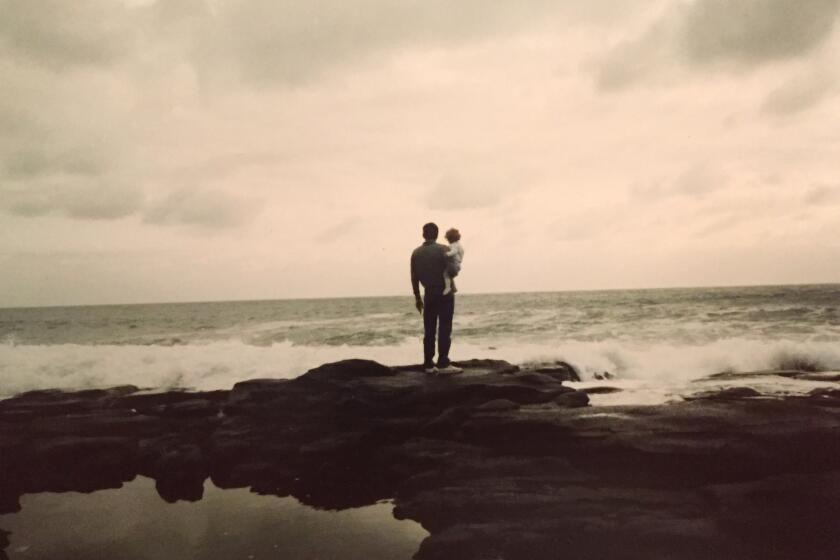

Two years ago, at my mother’s house in San Diego, I asked my 86-year-old Puerto Rican grandmother, who lives there, if she could show me photos of her parents. We were spending a lot of time together during the pandemic in a COVID bubble.

Abuelita Coco, a pale, parenthesis-slim woman, is losing her short-term memory. But she enjoys recalling fragments of her far-away past. She went to her bedroom to rummage through her closet. She pulled out photo albums of her life in Puerto Rico and placed them on her bed. We wore masks and were vaccinated, but I gave her space while she looked.

Later, she brought me a photo of a wiry, white-passing man. “That was my father,” she said in Spanish, peering at the photo with smiling eyes. “Y tu mamá?” I asked. She told me she had searched and searched for photos of her mother, and couldn’t find any. Perhaps she never brought them from Puerto Rico, she said.

I was perplexed. There was no way she forgot photos of her mother when she moved in with us when I was a teenager in the early 2000s. It occurred to me that maybe she didn’t want me to see her mother. I recalled a conversation I’d had with my father, from Mexico, when I was writing a book about his side of the family years before. He told me he thought my mother’s mother had Black ancestry. He could see it in her face, in my mother’s face. I objected that they look white. My father told me to look closer. But he said I shouldn’t inquire. He’d asked Abuelita Coco once and it made her “real mad.”

Without explaining myself, I asked Abuelita Coco for photos of her mother every time I visited. Each time, she thought I was asking for the first time. One evening, after weeks of gentle inquiries, she brought me a black-and-white photo. “That was my mom,” she said quietly. In the photo, a woman with high cheekbones and a coy smile rested her chin on Abuelita Coco’s shoulder. She wore a casual white dress. She was beautiful and undeniably Black, with dark chocolate skin. “Tu mamá era afro-puertorriqueña,” I said.

Abuelita Coco’s face crumpled. “Her skin was as white and as beautiful as mine,” she replied in Spanish, lifting her shirt to expose her pale belly. When I replied that there is nothing wrong with being Black, her eyes filled with tears. Perhaps her mother was “trigueña,” or wheat-colored, she said. But she certainly wasn’t Black.

Searching for public records online, I discovered that my great-grandmother Monserrate Torres was classified as “C,” or colored for Black, in the 1930 United States Census, which judged people with any detectable drop of Black blood as Black. On a later population schedule, Abuelita Coco, then 2, was also put on the Black side of the black-white binary. It wasn’t just my mother’s maternal side that was judged as Black. So was my mother’s father. And his mother was a seamstress named Pura Feliciano, labeled “mulatto,” part Black, when that was a designation. Pura’s father was “N,” for “Negro.”

Today, as I flip through Abuelita Coco’s albums, I’m bewildered by my former blindness to our afrodescendancy. On page after page I find photos of pale relatives beside relatives who look Afro Puerto Rican to me, including my mom’s brother, my Tío, who died of a heart attack more than a decade ago. I’d met many of these people on trips to Puerto Rico. My Tío had visited us in San Diego. Why had I never seen anybody’s Blackness?

Denigrating multilingualism is rooted in the desire to restrict who can belong here. Saying our true names is one way to fight that idea.

“My brother was not Black,” my mother tells me. She says he didn’t identify as Black. “He was white.” I scrutinize the photos, confused by her conviction. It’s true that when my Tío kept his hair short instead of his Afro and stayed out of the sun, he looked ambiguous. But activists and demographers recently mobilized to encourage more people in Puerto Rico to claim their Blackness to counter disproportionate white identification and to get a better idea of racial disparities that need addressing on the island. “Don’t you think if he were still alive he might identify as Black?”

“He’d identify as Puerto Rican,” she says. “He was Puerto Rican.”

It’s grating to talk with her about this. When I tell her about the government documents I found classifying her mother and her grandmother as Black, she concedes that her family had Black ancestry. But she sees me as obsessed with race; I see her as in denial about its ongoing role in this country. “We’re the human race,” she says, sharply. “Why are you looking at f––– race? To separate people like ganado, like caballos?”

I can’t tell whose mind is more colonized, mine or my mother’s. Racial identity is as personal as it is a product of how we’re seen. But how I see my relatives is different from how many of them see themselves. What if my mother is right, and I’m racializing relatives through my assimilated eyes?

“Do you check ‘Black’ on the census now?” my mother asks, exasperated with me. No, I don’t. I wouldn’t feel right claiming that identity on a government form, as someone who has benefited from white-passing privilege.

What I don’t understand is why I didn’t grow up encouraged to feel personally related to Black people. My mother doesn’t deny the Blackness of my 8-year-old niece, whose father is Black. She encourages her to be proud. She understands that my niece can’t be whole if she doesn’t embrace her diverse roots.

Why, then, is my mother’s perception of her own relationship to Blackness so different? I want to understand why she and Abuelita Coco draw such a hard line between themselves and Blackness. How did we come to be so ruptured?

Paranoia grows when immigration is discussed as an ‘influx’ and when Latino voices are not heard.

The year 1898 is when the U.S. seized Puerto Rico from Spain. Soon, Anglo Americans imposed on the island a binary concept of race at odds with the color spectrum that Puerto Ricans saw: blancos, negros, trigueños, mulattos, morenos, etc.

Puerto Ricans who thought they were a mix of white, Taino, African were seen by the Anglo Americans as Black. In 1909, President Theodore Roosevelt gave a speech celebrating “peoples of white, or European blood” expanding into lands of “mere savages.” In 1917, the U.S. gave Puerto Ricans second-class citizenship status: no voting rights or representation unless they moved to the mainland.

As Puerto Ricans traveled across the U.S. to work in fields and factories, they saw the segregation, lynching and massacres of Black Americans. Distinguishing themselves as non-Black became a matter of survival. During the early 1900s, Puerto Rico experienced a mysterious surge in “white” people on census records. In a paper, “How Puerto Rico Became White,” sociologists Mara Loveman and Jeronimo O. Muniz observe that the surge in white Puerto Ricans didn’t reflect a true increase in Puerto Ricans with white skin but rather an expanding concept of whiteness on the archipelago. The idea of who can be white became more inclusive due to “a precipitous rise in the perceived and actual costs of being seen by Americans as nonwhite.”

Many Puerto Ricans retained their hypersensitivity in distinguishing Afro features, but did not see those features as creating Black racial identity.

The erasure of Blackness was not entirely new; the cult of “limpieza de sangre,” or blood-cleansing, had been brought by Spaniards centuries before. Throughout Latin America and the Caribbean, Spanish colonizers created an elaborate caste system, with white people at the top, mixed-race people in the middle, and Black and Indigenous people at the bottom, enslaved or exploited for dismal wages. They’d brought millions of enslaved Africans to replace Indigenous laborers decimated by genocide and plague.

Namor, the brown antihero of the film, is no shallow villain. The actor and the character joined forces to send a larger message.

At the same time, that system used race-mixing and white immigration for blanqueamiento, or whitening of the population. The saying, “Hay que mejorar la raza,” or “We have to improve the race,” is still disturbingly common across Latin America. It means reproduce with a partner who will give you lighter-skinned children. Such bigotry is only beginning to be challenged.

After I explained some of this history with Abuelita Coco, she was angry and nodded in recognition. “Some people just think they’re so white,” she said. She recalled a taunt she heard growing up in Puerto Rico: “I’m whiter than you! I’m whiter than you!” But she continued to insist that her mother wasn’t Black. If anything, she was “india.”

In “Inventing Latinos,” UCLA law and sociology professor Laura E. Gómez writes that identifying as “indio” over Black is typical in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. In this context, it means mixed-race, another way of creating distance from the perceived bottom rung. “To say one is indio is to effectively say, ‘I am not black,’” Gómez wrote.

Abuelita Coco had grown too frail and forgetful to transform her perception of her mother. But I didn’t want to turn away from my great-grandmother’s Blackness.

In the middle of the last century, the Afro Puerto Rican poet Fortunato Viscarrondo wrote, “¿Y tu agüela, aonde ejtá?” The title, which is in Puerto Rican dialect, means: “And your grandmother, where is she?” It’s the poem’s refrain, directed at a light-skinned Puerto Rican who is racializing the poet, calling him “Negro.” The narrator repeatedly asks the light-skinned man where his grandmother is. The implication is that the light-skinned Puerto Rican is hiding her because she’s Black.

I read the poem after listening to a “Code Switch” episode featuring a song based on the poem, which is in the Puerto Rican dialect. At first, I struggled to comprehend the poem on the page, but when I sounded out the words, my ears heard a language of my childhood, the one my Abuelitos spoke before their accents changed from years in a state where most Latinos are Mexican American. (Puerto Ricans are less than 1% of Californians.) The spoken word conveys the poem’s meaning to my ears. The light-skinned man’s grandmother is hidden “po’que ej prieta de a beldá.” Because she’s a Black woman.

This poem helped me grasp why I had never seen a picture of my great-grandmother: her dark skin was proof that my family wasn’t really white.

The Trump movement tainted this symbol with bigotry, but we can take it back.

Many white Americans’ concept of whiteness categorically excludes Latinos. But for decades, a majority of Puerto Ricans identified as white alone: 75% on the 2010 Census. That’s changing fast with the continuing economic crisis, discrimination and new racial justice movements. In 2020, the share of Puerto Ricans who identified as white alone plunged to 17%.

Despite efforts to encourage Black pride and Black identity in Puerto Rico, most are still predominantly declining to identify as Black people, including many who would be seen as Black by white Americans. Instead, there was an explosion in those identifying as two or more races, from 3% in 2010 to half of all Puerto Ricans in 2020, as well as a jump in those identifying as “some other race alone,” from 8% to a quarter of them.

The trends mirrored a drop in white identification among all U.S. Latinos, from more than half to 20%, and surges in those who choose two or more races (from 6% to 33%) and “other” (from 37% to 42%). “Other” is now the second-largest race in the country.

The rise of the “other” is giving birth to a new way of understanding race in America: one that isn’t rooted in a binary but rather a spectrum that resembles Puerto Ricans’. The Biden administration’s proposal to add “Latino” as a race category on the 2030 census is appealing to countless Latinos who can’t find themselves in existing categories.

The rise of this Other/Latino race is nerve-wracking to white nationalists and GOP propagandists who are openly plotting to encourage white identification among Latinos. If aspirational whiteness among Latinos goes extinct, so too may white supremacist rule. But if the Other/Latino race defines itself in opposition to Blackness, it could end up replacing white supremacy with something similar: mixed-race supremacy, or mestizaje, a common feature of the anti-Black and anti-Indigenous pigmentocracies in Latin America and the Caribbean, exhibited by Latino members of the Los Angeles City Council who disparaged Oaxacans and “Blacks” in the now-infamous leaked audio recording.

What they failed to grasp, and what I failed see until finding my great-grandmothers, is that Blackness, like Indigeneity, is at the heart of who we are. Latinos must recognize, resist and reverse centuries of blanqueamiento. We the outcasts of Latin America must remember who we came from.

Geographic proximity to Mexico made it easy for me to learn about my father’s country. As a child and teenager, I regularly crossed the border. Then I moved there in 2010. Living in Mexico City, I often heard the words “indio” (Indian), “indígena” (Indigenous) and “negro” (Black) hurled at dark-skinned people as synonyms for subhuman.

This vitriol is not a Mexican problem but a European disease that has plagued Latin America and the Caribbean for centuries. Most Latin American countries, upon gaining independence from Spain, formalized equality. But descendants of colonizers clung to the wealth they’d derived from the exploitation of Black and brown bodies.

They formed a devil’s bargain with Anglo elites, allowing U.S. corporate colonialism and militarism in Latin America, including U.S.-backed coups and massacres, to preserve the dominance of European-blooded people across the Americas.

Even now, law enforcement across Latin America works with organized crime, armed with U.S. guns, to uphold white power, with assassinations and forced disappearances of hundreds of Black and brown people who resist foreign-owned extractive mega-projects.

“Latin America is the region of open veins,” the Uruguayan journalist Eduardo Galeano famously wrote in 1971, explaining that everything in the region has long been robbed and turned into European or U.S. capital. “Everything: the soil, its fruits and its mineral-rich depths, the people and their capacity to work.”

The parasitism is disguised as Black and Indigenous integration. In 1924, Jose Vasconcelos, Mexico’s former education secretary, wrote the influential essay, “The Cosmic Race,” promoting mestizaje, or mixed-race supremacy. It conjured a “synthetic race” superior to all the rest, a mix of all races, via absorption of Black and Indigenous people — rationalizing their continued rape, pillaging and dispossession.

U.S. Latinos come from those displaced people. Amnesia about our origins inspires our self-destruction: participation in border vigilante groups, hate groups and absurd competitions based on imagined distance from Blackness, with many Dominicans looking down on Haitians and many Puerto Ricans looking down on Dominicans.

In her 2022 book, “Racial Innocence,” Tanya Katerí Hernández, a Fordham University law professor and Afro Puerto Rican expert on Latino anti-Black bias, critiques the delusion that Latinos’ “racially mixed cultures immunize them from being racist.”

Hernández recalls the story of her mother, Nina, rejected by her family because of her darker skin and “kinky curls — pelo malo (bad hair).” Some maternal relatives wanted her placed for adoption with an African American family. “Any African American family would do, as long as baby Nina was removed from the household,” Hernández wrote.

She was beaten, threatened with expulsion and denigrated, while her sister Mónica was beloved for her lighter skin and straight hair. Their physical comparison was “a constant obsession of the family with Nina being called ‘monito’ (little monkey), and negrita bembe (little Black African-like girl), while Mónica was simply called la nena (the little girl),” she wrote.

The story is sadly not uncommon among U.S. Latinos. One 39-year-old East L.A. resident who asked me to refer to her only as B told me that her Guatemalan mother often said her sister was beautiful because she “took after the ‘Spanish’ side,” lamenting that B was “morena,” with “a flat nose and darker face like her grandma who was ‘indígena.’” B’s mother told her she’d need a nose job as an adult. The abuse hurt B’s self-esteem and motivated her to wear green contact lenses and dye her hair blonde in high school. “It impacted how much I was able to love and celebrate myself, and how confident I was in the world,” she told me. Today, she encourages her son to be proud of his heritage.

Internalized white supremacy functions as a kind of auto-immune disorder, turning us against our bodies in discrete and violent ways, from skin bleaching to self-cutting, substance abuse and suicide. It divides families. Some parents hide or physically alter children whose looks betray the family’s Blackness or Indigeneity. As Puerto Rican-Dominican comedian Aida Rodriguez described on a Netflix special, her Puerto Rican relatives were always trying to “blow-dry the Dominican out of me.”

Many Latinos are challenging such abuse and annihilation of Blackness and Indigeneity. They’re raising their children differently, educating relatives and creating art to reshape the culture. Yosimar Reyes, a Mexican-born poet and activist, created a one-man show, “Prieto,” a term for dark-skinned, to subvert ideas about brownness as ugly or lowly.

It was inspired by his brown queer youth in East San Jose with other undocumented people from Indigenous Mexico. “I just grew up thinking we were ordinary, that there was nothing special, nothing magical about us,” he recalls. “Maybe if you had blue eyes or green eyes there was something interesting about you. But we were regular.”

They were farmworkers, dishwashers and other people who sustain the American economy in the shadows. “We’re like this mugre, this stain that people don’t want to see,” Reyes told me. “But if you think about it, we are integral to everything.”

Black Latinas are similarly fighting for greater visibility. “The way I look and my history is not what is promoted as Latina in mainstream Latin, Caribbean or U.S. pop culture,” the Puerto Rican art curator María Elena Ortiz told me. Her exhibitions center what she sees as “an Afro-Latin sensibility,” such as a coming project with Marina Reyes Franco featuring Black Puerto Rican art at Puerto Rico’s Museum of Contemporary Art.

In her forthcoming memoir, “American Negra,” Natasha S. Alford explores growing up at the intersection of Black American and Puerto Rican identity. “Black identity is often framed as a negative,” she said of Puerto Rico. There, it’s often equated with slavery, “in the sense of victimhood, not necessarily emphasizing their resistance or contributions.”

With her project Ancestral Black Women, the Puerto Rican writer Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro reframes Black identity by unearthing stories of Black women who rebelled against slavery. “We have to rescue their stories,” she said in a TedX talk. She urges people to ask: “What do you know of your grandmother, of your bisabuela, of your tatarabuela?” Also, “Do you have any relic? Do you have any copy of a document?”

I’m grateful to my grandmother for showing me a photo of her mother, even if it took time. I believe it was brave, and in a way, an act of resistance against Black erasure.

My appearance reflects generations of that Black and Indigenous erasure. But I know that I carry the remnants of my ancestors: a quarter of me is from Sub-Saharan Africa and Native America, per DNA tests. When I look in the mirror, I can’t find my bisabuelas at first. I see the jawline of a white cop, my grandfather’s father, who wouldn’t recognize his mixed-race son until the boy’s mother Pura died. I see the green eyes of a Spanish man who raped my Mexican grandmother Carolina when she was a teenager.

But farther down, on my left rib cage under my heart, there’s a brown birthmark in the shape of an upside-down Mexico. I like to imagine that my Mexican tatarabuela Juanita, a curandera, or healer, descended from Indigenous Caxcans, left it there to say: “No te olvides, gringa.” Don’t forget, gringa.

I like to imagine that the women who preceded me, the ones who toiled in a caste-ordered world, can possess me. It’s not me on that stage or TV. It’s my bisabuela Pura, who died of pneumonia at 34, my age. She has come back to haunt today’s bigots.

My people and I have a heritage that encompasses half of the world. Our strength is cross-border and cataclysmic for those who aim to reduce humanity. At the core of our powers are the Black and brown women who cannot and must never be extinguished.

Jean Guerrero’s book “Crux” was published this month in paperback. @jeanguerre

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.