Opinion: I was shot in the Southern California desert. Why? That’s the wrong question

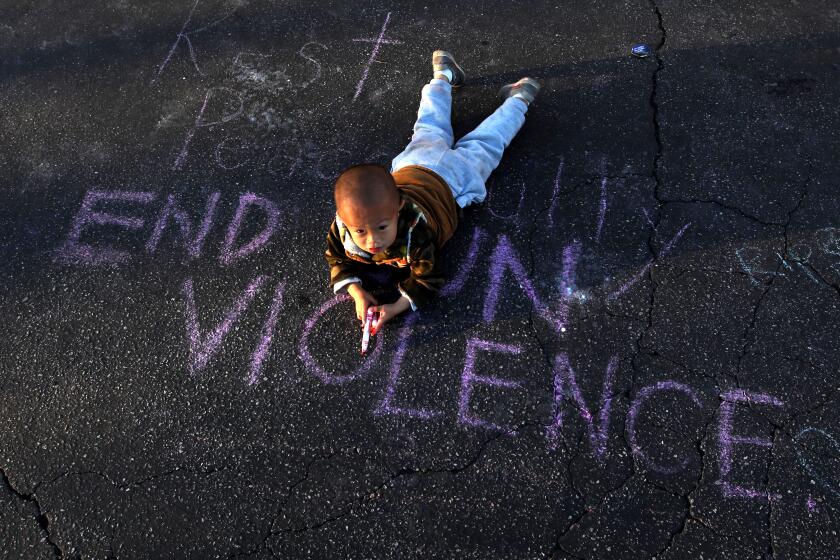

Why do we keep treating gun violence in the U.S. as a series of isolated incidents instead of an out-of-control epidemic?

Why do we seek the motive of the shooter, as if that knowledge offers protection from future acts of violence, perpetrated by other shooters?

A year and a half ago, on a morning in late summer, I was driving through the California desert, leaving a school camping trip early to make it back to Los Angeles for a cousin’s wedding. It was an ordinary morning, until it wasn’t.

I came upon a man weaving on foot in the middle of the empty two-lane highway. On the side of the road was another man, standing next to a white car. A red gasoline container sat on its hood.

I had no intention of stopping. I knew better.

But I slowed down to avoid hitting the man in the middle of the road, and suddenly he was in front of my car, pointing a gun at me.

I stopped.

Since the Reagan era, courts and politicians have allowed personal liberty to overshadow the common good on guns and the 2nd Amendment.

With the gun aimed at me, he walked toward me, then past me, then opened the door to the back seat on the driver’s side. He hadn’t even noticed the wallet I’d tried to hand him through the crack in my window.

I remember looking over my shoulder and seeing him lean into the car, rifling through the heap of camping gear in my back seat, looking confused. I don’t know how many seconds passed between when he opened the door and when I hit the accelerator.

I was frozen, until I wasn’t. I hit the gas, and the man stumbled back, thrown off balance. Before my car had picked up any significant speed, with the back door still wide open, I heard a pop.

I didn’t realize it until much later, but I survived by the breadth of a breath. I had been leaning forward in my seat. The bullet went through my backrest and hit a spring. The body of the bullet went right, and a sliver of a fragment hit me when it deflected left. I ended up with a grotesque bruise and scrape the size of a fist on my back and the lingering effects of the trauma in my body and my brain.

It’s hard to make sense of both how unlucky and lucky I was, all at the same time.

Then again, the senselessness of gun violence defies logic.

In the end, the question I was left with was not why the shooter did it, but why he could do it. What are the larger systemic structures that leave us so unprotected, so vulnerable to the vicissitudes of a would-be-shooter’s possible motives?

We once thought Sandy Hook would be the last straw. But there have been so many mass shootings in the 10 years since, we can’t remember them all.

The truth is that even as I hold the man who perpetrated the crime against me fully responsible for his actions, trying to imagine the paths that might have led him to the middle of the desert that day was an exercise in empathy. But trying to pinpoint his motive was an exercise in futility; it brought me neither clarity nor comfort.

I know that the story is not as straightforward as the crime of attempted carjacking that he eventually pleaded guilty to. I know that the man who shot at me was a person with a felony record who shouldn’t have been in possession of a firearm. I know that the night before I came across him on the road, he pulled a gun on police, leading them in pursuit and evading arrest.

I also know that I was the predictable victim of a political system that has allowed close to 400 million guns to flood every part of our country.

The man was captured and brought into custody without incident two days after our encounter. He is in prison now, but the truth is that I don’t feel any safer.

The truth is that what I feel is rage.

But my rage is not reserved for him. My rage is reserved for the courts that place greater value on an antiquated interpretation of the 2nd Amendment than they do on human lives. My rage is reserved for the politicians who fail to pass common sense gun reforms, including universal background checks and assault weapons bans, that would make all of us safer.

In 2020, 45,222 people died from gun-related injuries in the United States. Of those, 19,384 were murders. That’s nearly 53 each day, or a little over two every hour.

Why do we keep allowing this?

Calina Ciobanu is a teacher and writer in Los Angeles.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.