My grandson Joshua died from fentanyl last month.

This beautiful and vibrant young man was 22 years old. He was part of my large, blended family — white, Black and Mexican — in northern Illinois.

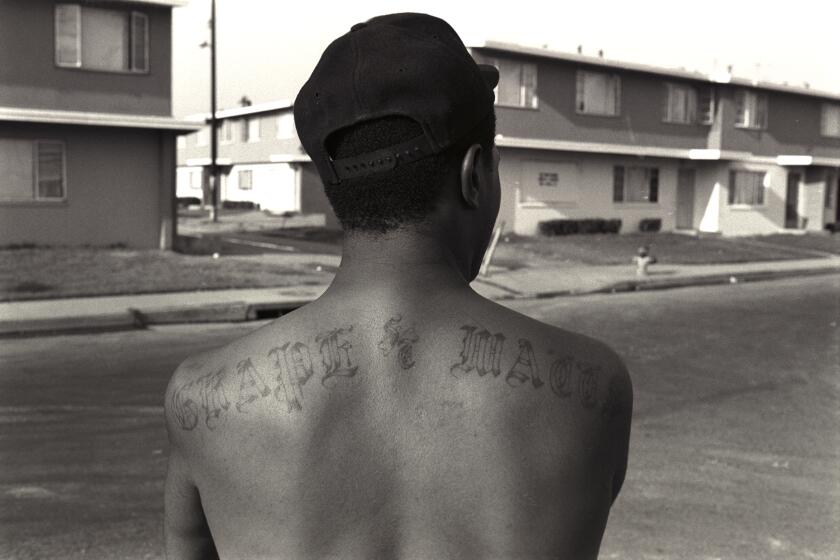

Joshua was technically not my blood grandson. He was the half-brother of my blood granddaughter Ana, daughter of my oldest son, Ramiro. Joshua had two other brothers, both amazing young men, one in the Army. Since they were babies, all three brothers called me “Grandpa Louie” like Ana did. The boys’ father was Ramiro’s best friend and a former Chicago gang youth whom I helped — although he did 90% of the work — leave behind the vice grips of street life and jails. I practically adopted him, and together we all worked hard to get out of worsening violence, drugs and crime. His sons with Ana’s mom, and son with another woman, are my grandkids, no matter what.

In L.A. County, the number of deaths linked to fentanyl rose from 109 in 2016 to 1,504 in 2021, the county public health department found.

I loved Joshua. He deserved a better world. Yes, he was troubled, like many of the struggling young people in this part of Illinois who have been affected as jobs left and drugs rushed in. Our family protected Ana and her brothers as best we could from the inner-city world their fathers grew up in — my son Ramiro ended up in prison, including for a 13½-year stretch. But drugs like crystal meth and fentanyl know no boundaries. Many well-raised and good people get snarled in their ever-expanding web. Ana is currently incarcerated for drug-related charges. Government data show that in 2021, nearly 108,000 people in the U.S. died of drug overdose — more than 71,000 from synthetic opioids, mostly fentanyl.

Chicago, not far from where Joshua lived, is my second home. I lived there for 15 years. My two youngest sons were born there. I have a daughter and two grandchildren still in the city, and Ana has two daughters (my great-grandchildren) who live in northern Illinois. There’s another granddaughter and four other great-grandchildren in the middle of the state. Now I’m in the San Fernando Valley, where I’ve been for 22 years. But the helplessness families often feel when they lose a loved one to drugs or violence is much the same, regardless of where you are.

No matter how many laws are enforced, how many prison sentences or police officers are deployed — often with military gear and equipment — drug and gun violence continue unabated. When Joshua died, we were remembering the gun murder a year before of the 15-year-old son of my daughter’s high school friend who we also helped when she was a teenager. Her son was killed by gang youth — and he was neither in a gang or in deep trouble. When I went to Illinois recently for Joshua’s funeral, we did Indigenous prayers and songs for the parents who lost sons within a year of each other (I have Indigenous roots from Mexico).

We must turn our sense of helplessness into healing and then action.

Politicians like to spout “tough on crime” policies, which for the last 40 years have been given full rein. They’ve failed.

Instead, let’s try caring and community strengthening. Let’s try faster and more comprehensive drug treatment, full mental health services and healing arts practices, which have shaped my community work in the Valley. I’ve advocated for these approaches when I worked with Chicano gang youth in Los Angeles during the 1970s and early 1980s; with Bloods and Crips as well as Chicago youth both in and out of gangs in the 1990s; with young people in Mexico, Central America, South America, England and Italy — and when I returned to the Los Angeles area in 2000.

Days before the 1992 L.A. uprising, Crips and Bloods took a stand for peace.

In the largely working-class Latino and Black community of the northeast San Fernando Valley, my wife, Trini, and I helped create Tia Chucha’s Centro Cultural & Bookstore, which also offers a program called Trauma to Transformation that sends artists, poets and theater workers to prisons, juvenile lockups and parolee housing. I know from experience that these mentoring and guidance programs help people.

Unfortunately, our leaders have not shown the political will to provide proper funding and infrastructure to reach every community in need. I appeal, then, for all of us to work together so our children, regardless of race or income, can be given a chance to thrive, not just struggle to survive.

No more helplessness. These are human-made problems that we have the creative capacity to solve. Bring the most impacted people to the fore of efforts to stop violence and destructive drug use — we can make the difference.

For all the Joshuas of the world, let us now become embracing and proactive. As South L.A. community leaders declared when brokering a historic gang peace treaty just before the 1992 L.A. uprising, give us the tools — the “hammers and the nails,” if you will — and we will rebuild our communities.

Luis J. Rodriguez, former poet laureate of Los Angeles, is the author of 16 books, including the memoirs “Always Running, La Vida Loca, Gang Days in L.A.” and “It Calls You Back: An Odyssey Through Love, Addiction, Revolutions & Healing.” His 2001 book “Hearts & Hands: Creating Community in Violent Times” summarizes 50 years of work in urban peace and community healing.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.