Column: Is the documentary ‘Navalny’ a life insurance policy for the imprisoned Russian opposition leader?

As Vladimir Putin wages his misbegotten war on Ukraine, there’s another, quieter war he’s prosecuting, this one against a 46-year-old man who sits in a Russian prison, in solitary confinement, on trumped-up charges of fraud.

Alexei Navalny, the Russian anti-corruption crusader and cheeky YouTube star, is the face of democratic opposition to Putin’s presidency. He is, Time magazine declared in January, “The Man Putin Fears.”

Obviously, he must be crushed.

In August 2020, Navalny fell desperately ill on a plane en route to Moscow from Siberia, where he had been campaigning for allies in local elections. Pilots made an emergency landing, and two days later, under international pressure, Russians allowed him to be flown to Berlin, where doctors confirmed he’d been poisoned by the nerve agent Novichok. Poisoning, as the world knows but Putin denies, is a signature of Russia’s security service, the FSB.

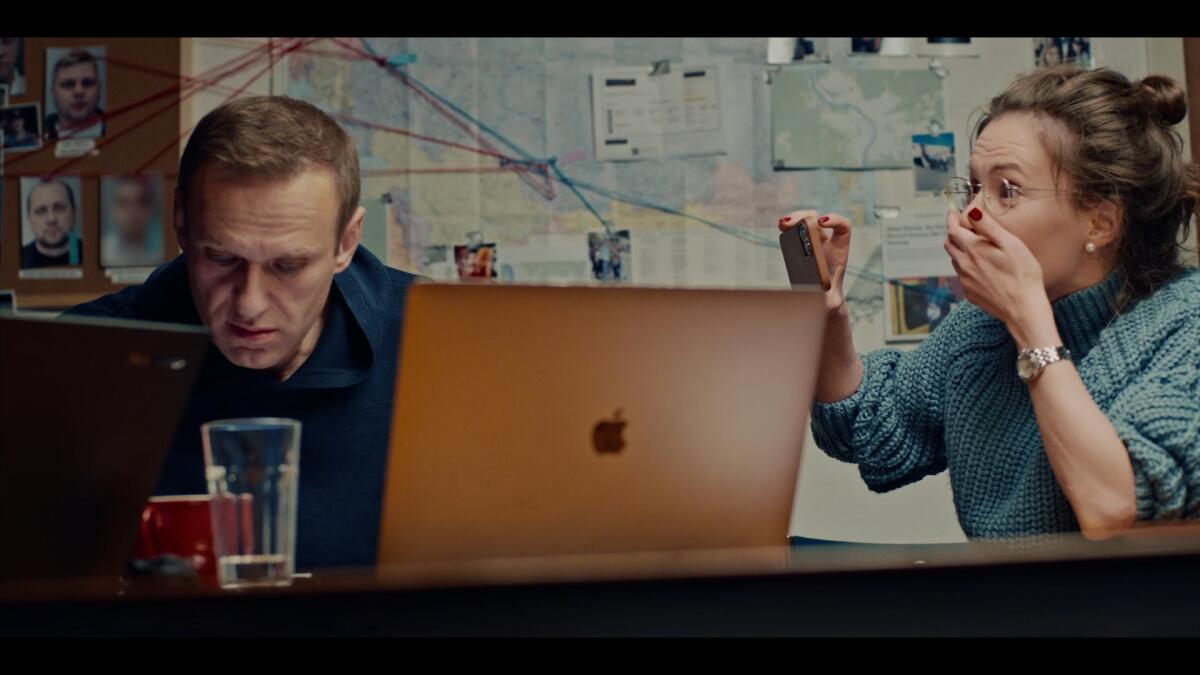

Four months later, thanks to CNN’s reporting and the extraordinary online citizen journalist collective Bellingcat, which purchased phone data on the black market, Navalny was able to identify the men he believes tried to kill him. One by one, he called them up. When he confronted them as himself —It’s Alexei Navalny calling and I was hoping you could tell me why you wanted to kill me? — they hung up. But when he posed as an official of Russia’s Security Council investigating the botched assassination, they talked.

The emotional climax of a new film about Navalny is the moment he gets one of his would-be assassins, a military chemist named Konstantin Kudryavtsev, to admit the nerve agent was placed in Navalny’s underpants.

On Monday, thousands of miles from the 5-by-11-foot cell where Navalny is allowed to read one book every two weeks, his colleague Maria Pevchikh sat on a low riser in a tented garden of the elegant Four Seasons Hotel in Beverly Hills, at a luncheon organized to showcase the work of Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation.

Daniel Roher’s Sundance prize-winning documentary reopens the investigation into the 2020 poisoning of Alexei Navalny.

Pevchikh is on a breakneck international tour promoting the documentary — directed by Daniel Roher and broadcast on CNN and streaming on HBO Max, in which she, as head of the Anti-Corruption Foundation, is a featured player.

Pevchikhand many other Navalny colleagues are in exile, wanted by Russian authorities for a bevy of made-up crimes, most recently terrorism and extremism. Pevchikh lives in Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital, and has made peace, she said, with the possibility of never living in Russia again.

She may be on a PR tour, but something far more important than box-office success or Hollywood awards hardware is at play. The documentary, she believes, is one way to keep Navalny alive, not just physically, but in the world’s imagination.

“Putin,” she told the gathering, “wants Navalny to be irrelevant. We were aware that this film was life insurance.”

“Navalny” has gotten the kind of attention most filmmakers yearn for: two top awards at the Sundance Film Festival, where it premiered in January, and a slew of other honors.

On the second anniversary of the poison attack on Alexei Navalny, Germany and the United States have hailed the determination of the Kremlin critic who is imprisoned in Russia.

Shortly before the Four Seasons event, Pevchikh and I met in the lobby of the Palomar Hotel in Beverly Hills, where we talked about how she ended up as Navalny’s lieutenant, exposing Russian corruption on a global scale. In the last two years, the Anti-Corruption Foundation’s videos have traced ownership of a sprawling billion-dollar-plus palace complex on the Black Sea to Putin — which he denies. They have linked Putin to a $700-million yacht, the Scheherazade, that was seized in May by authorities in Italy after the foundation and the New York Times exposed its links to the Russian president — which he denies.

Pevchikh, 35, was born in Moscow and started college at Moscow State University when she was 15. She was put off, she said, by professors soliciting money from students for better grades.

“I quickly figured out if I want to get something that looks like an education,” she said, “I need to start over.” At 18, she enrolled at the London School of Economics, studied political science and discovered Navalny, who had become well known in Russia as an anti-Putin blogger.

“He would write about politics in such a funny way,” she said. “He’s a brilliant writer.”

While she was in London, in 2006, a former FSB agent and vocal Putin critic, Alexander Litvinenko, was poisoned with military-grade polonium in London. His death, which generated international headlines and outrage to match, was slow and agonizing.

“I remember sitting in a class surrounding by students who said, ‘Maria, why is your president doing that? You can go to the middle of a foreign country, contaminate half of London and just kill someone you are unhappy with?’ It was embarrassing.”

Alexei Navalny, Russia’s most prominent opposition leader, loses another court battle in his war against the Kremlin’s widening crackdown on dissent.

Four years earlier, she said, she had been shocked at the incompetence of Russian police during a hostage siege in a Moscow theater. Islamist separatists held about 900 people hostage for three days, threatening to blow up the theater unless the government withdrew troops from Chechnya. Russian police pumped a narcotic gas into the theater, and at least 125 hostages died because police did not administer the antidote shot that would have saved them, nor turn them onto their stomachs so they would not choke on their own vomit, among other blunders.

“I knew I wanted to try to change what’s happening to my country,” Pevchikh said. “It was like Putin was destroying the country and I couldn’t understand why one man would be able to do these awful things.

In 2011, she was back in Moscow and saw that Navalny had advertised a job opening for a lawyer at his foundation. She used the posting to get a foot in the door.

“What does a 22-year-old girl do to stop Putin?” she asked. “Through Navalny, I found this vehicle.”

In January 2021, after he fully recovered from the poison, Navalny returned to Russia, knowing that he faced a good chance of being arrested. Roher’s cameras rolled as Navalny and his wife, Yulia, landed. He was immediately detained by police and has been in custody ever since. In January, he is expected to face a new trial on charges that his Anti-Corruption Foundation is a terrorist organization, and he could face a sentence of 30 years, on top of the nine he is already serving.

There’s no way of knowing, however, what Putin will do.

“The man is chaotic,” Pevchikh said. “He is not governed by any logic. It’s equally likely that tomorrow Putin decides to free Navalny, have a democratic election and just pretend that nothing has happened, and the probability is exactly the same that tomorrow he nukes the whole world.”

Putin is unmoved by criticism or shame. He was emboldened enough to put Navalny in prison for the crime of wanting to oust him, and surely wants his No. 1 critic dead. That critic may be locked away in a Russian prison, but the movement he inspired carries on.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.