Op-Ed: Kids keep getting sick, overwhelming parents once again. Will the U.S. offer us any help?

If you’re a parent with a young child, odds are that your child is or has recently been sick, sending you and your partner scrambling to figure out who will miss work again to stay home.

My kids have been sick off-and-on since the weekend after preschool orientation. My 4-year-old visited her classroom on a Friday morning. By Monday she was running a fever and had to miss the first day of school. That mid-August virus lasted just long enough for her to return to class and bring home RSV, from which it took all four members of my family longer than two weeks to recover. We all developed infections that required multiple rounds of antibiotics and steroids.

Before they’d even finished their antibiotics, my kids caught another virus. And another one. The pediatrician’s office became our second home and, for two months, someone in my household was running a fever. My 2-year-old had so many consecutive ear infections that he needed surgery to put in tubes.

Has childcare been a factor in your decision to quit your job or delay finding work? If so, we’d love to hear from you.

Our family’s trajectory is not unusual right now. Unprecedented levels of RSV and flu, alongside an uptick in COVID cases, have overwhelmed pediatric hospital systems and led to shortages of medications that treat common childhood illnesses (Tamiflu, amoxicillin, albuterol).

Making things worse, this surge is coinciding with a child-care crisis marked by staffing shortages, closures and a lack of affordable options.

As a result, more than 100,000 Americans missed work in October because of child-care problems, the highest number ever recorded in the U.S. — even greater than at the height of the pandemic.

Most of my friends were among that 100,000. Some have been able to attempt working from home while nursing sick kids on the couch. But a couple I know in New Mexico missed a combined 13 days of work during the seven-week period when their 2-year-old twins got COVID; hand, foot and mouth disease; RSV and other fever viruses, prompting two closures of their day care. Another friend in Tennessee returned from her 14-week unpaid maternity leave only to have her baby catch a stomach bug the first week at day care, which kept mom and child home together again the next Monday.

Based on my experience, text chains and social media feed, I wasn’t surprised when I read the more-than-100,000-Americans statistic. Seeing it, I felt both vindicated and despondent. Every time a temperature spikes or a prescription needs to be picked up or the pediatrician’s office calls me back to schedule an appointment for my child, being a stay-at-home parent feels logical — while returning to work feels even more out of reach.

I stopped working my part-time job as a private tutor when COVID hit and my daughter’s preschool closed on March 13, 2020. The decision became official once my son was born two weeks later. Even before the lockdowns, finding child care was a challenge. My mom died just four months after my daughter was born, meaning I didn’t have the larger family safety net — typically a grandmother — so many of my peers rely on when their kids fall sick, or to fill the gaps between when kids need to be picked up and workdays end.

During the spring and summer of 2020, school closures and shelter-in-place orders meant that I did all the child care while my husband worked. With a newborn and a toddler, I had no other option. Even after lockdowns ended, I chose to stay home to lessen their exposure to the virus.

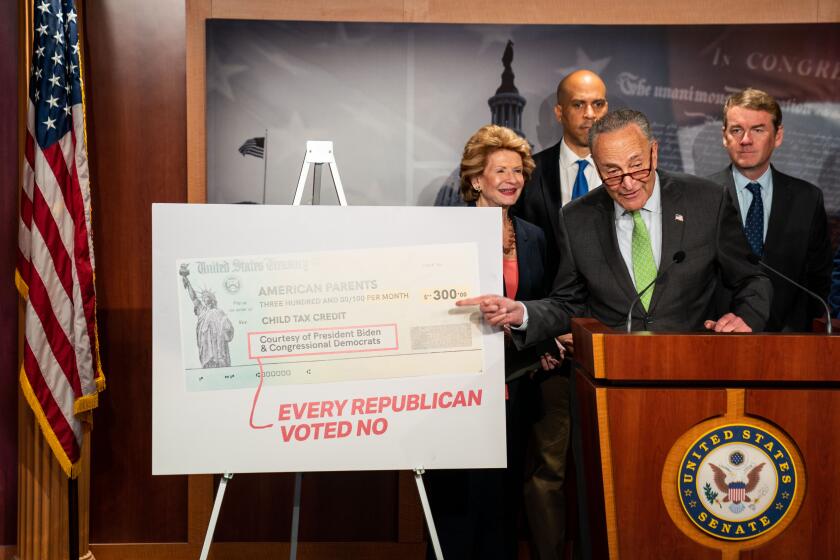

Congress should use its lame-duck session to bring back the expanded child tax credit, a groundbreaking policy that immediately cut child poverty in half.

Now, as pandemic year three comes to an end, both of my kids are finally vaccinated and in preschool part of the week. I had hoped to use this year to start working part-time while searching for a teaching job for next year. But the collective number of sick days this fall has been overwhelming. I can’t imagine finding a full-time job with the flexibility to accommodate our never-ending, impossible-to-plan-for child-care needs.

Other than a child tax credit that hasn’t been renewed, the U.S. has not instituted any major policy to help parents since the pandemic started and exposed our country’s broken child-care system.

The U.S. remains one of just eight countries in the world without a national paid parental leave policy — and the only member of the 38-country Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development without one.

Most OECD countries also offer child-care-giving leave, sometimes called home-care leave, allowing a parent to provide short-term care for sick children without sacrificing pay. This type of leave acknowledges the realities of having young children. Finding a job that guarantees it would offer me the flexibility to care for my children when they have fevers, coughs, stomach bugs, sore throats and every other symptom that parents across the country know too well. It is a crucial tool to keep parents in the labor force and limit the viral outbreaks that strain schools, day cares and families when parents feel forced to send their sick kids.

Access to paid parental and caregiving leave should be a basic right. While paid leave alone isn’t a panacea for child-care needs, it is a big step in the right direction.

Kids get sick. Sometimes, such as this fall, a lot of them do. By bringing our paid leave policies up to the standard of other countries worldwide, the U.S. can start to support the parents of sick kids — and the economy that depends on them.

Sarah Hunter Simanson is a Memphis-based freelance writer who received her MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts and is working on her first novel. @sarahsimanson

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.