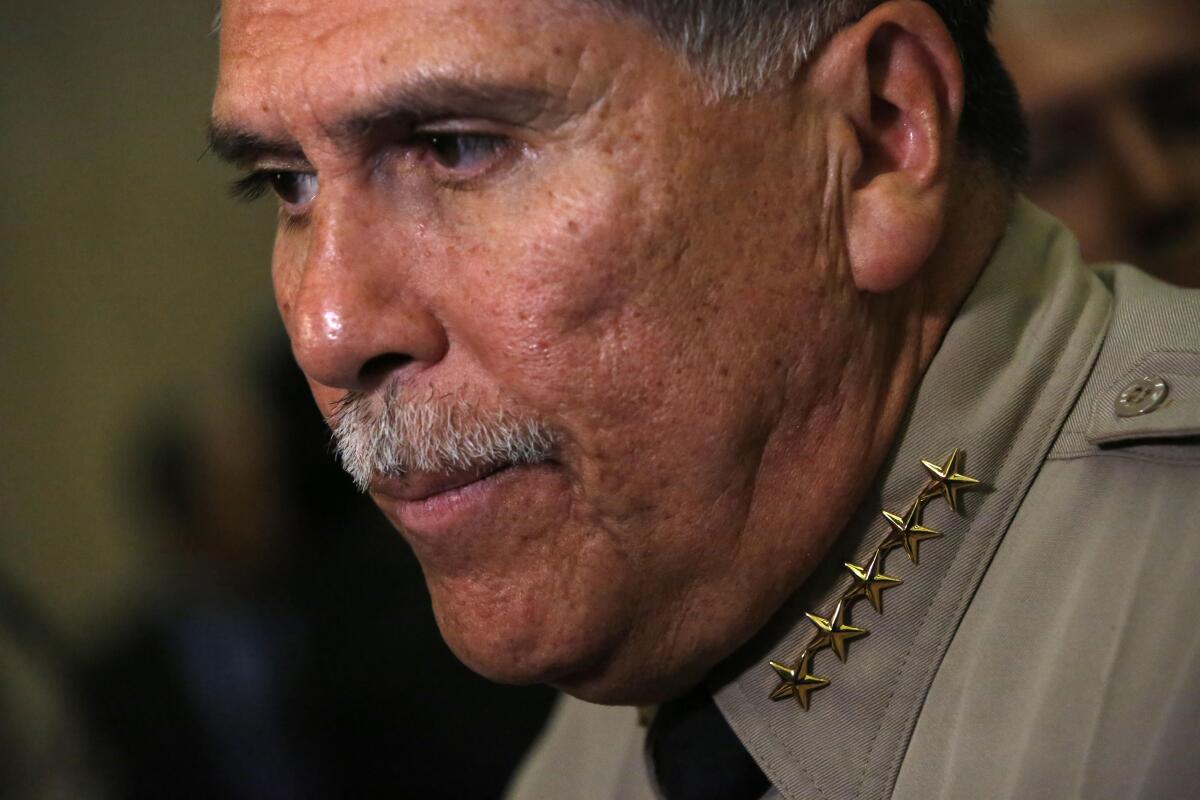

Editorial: What Sheriff Luna is up against as he takes over the troubled department

Robert Luna, who just completed his first week as Los Angeles County sheriff, was elected in large part to restore the sense of order and confidence that characterized the department through much of the 20th century.

That era of stability began after the Board of Supervisors engineered the ouster of the last of the Wild-West-era sheriffs, John C. Cline, and installed attorney, deputy Supreme Court clerk and USC football coach William I. Traeger in the 1920s. When Traeger left for Congress, the board picked his undersheriff, Eugene Biscailuz, then Biscailuz’s undersheriff, Peter Pitchess, and then Pitchess’ undersheriff, Sherman Block. These were department insiders, mentored and anointed by their predecessors, embraced by county supervisors and confirmed by the voters with little discussion or controversy, serving multiple-term tenures.

And then came Lee Baca in 1998, who went to federal prison two decades later for obstruction of justice. Followed by outsider Jim McDonnell, who tried to clean up Baca’s mess but was ousted after a single term by Alex Villanueva, who managed to keep himself and his department in the headlines — and not in a good way — throughout his single term.

Luna’s challenge is thorny. Like McDonnell, he is a Sheriff’s Department outsider — a former Long Beach police chief — and will face the same skepticism from the ranks of more than 9,000 deputies. The department has an internal culture of suspicion, exacerbated by a decentralized, station-based structure that has played a role in fostering deputy gangs. It has become a culture, Capt. Britta Steinbrenner said at a candidate’s forum in January, of “self-survival and backstabbing.”

Robert Luna would be a much better sheriff than the disastrous Alex Villanueva

Luna has to retain the support of the Board of Supervisors, which exercises enormous authority over the department’s budget. The board is wisely backing a “care-first” approach to public safety issues that requires reassigning some traditional law enforcement tasks to unarmed clinicians and social workers. The newest supervisor, Lindsey Horvath, made her mark on the West Hollywood City Council by helping to lead a move seen by many deputies as a blatant example of “defunding” by decreasing sheriff presence in the small city and reallocating funds to “security ambassadors.”

Meanwhile, Luna has to restore public confidence that evaporated during Villanueva’s term, figure out what to do with the decrepit and dangerous Men’s Central Jail, dismantle deputy gangs, make nice with cities and agencies who contract for sheriff patrols, and fight crime that jumped after COVID lockdowns were eased in 2020.

Many of these tasks are in conflict with one another. Luna knows that. It doesn’t seem to bother him.

“I’m all in,” he told The Times editorial board last week. “I’m completely committed. And I think the people here” — his top staff, and by extension the whole department — “are as well.”

We take him at his word, and L.A. County residents should as well, but not in the deferential 20th century fashion. Luna himself noted at a candidates forum earlier this year that “the world has changed around us” and there can be no return to a status quo that may never have served Los Angeles County residents all that well.

L.A. County Sheriff Alex Villanueva wasn’t wrong about everything. New Sheriff Robert Luna should take note of what his predecessor understood.

For example, each of those multidecade sheriffs successfully pressed the supervisors to keep expanding jail capacity, and they kept them full. Men’s Central Jail became a breeding ground for deputy gangs and for unwarranted violence inflicted on inmates who were often there because the county lacked the foresight to build mental health and substance-use treatment clinics that would better serve them, and the public at large.

The Board of Supervisors in 2019 saw the foolishness of continuing on the same course, scrapped plans for a replacement jail and committed to its care-first program. But Men’s Central Jail still stands, and is still nearly full.

At the January forum, the candidates were asked whether they would support replacing Men’s Central Jail with a new, modern jail. Each candidate had signs that said “Yes” on one side, “No” on the other. Every candidate held up the “Yes” sign but one. It wasn’t Luna. He said “Yes” to a new jail.

Later, he told The Times editorial board that he was learning more each day about the situation and was open to tearing down the aging jail and replacing it with treatment instead of jail beds (the county has several other jail facilities). That’s good to hear. Luna is no pushover, but he appears to be a man who listens.

On the same day he was elected, L.A. County voters also passed Measure A, which allows a supermajority of the Board of Supervisors to remove the sheriff for cause. It changes the political dynamic regarding independent sheriffs, but in a sense, it doesn’t change it all that much. Recall that the board ousted a sheriff in the 1920s, and appointed or anointed many of the successors. The job requires cooperation, and Luna appears to know how to engage without giving in.

He opposed Measure A, but he took the vote “as a reminder to us that none of us are above the law.” It’s what happens, he said, when the public loses faith.

Luna comes in on a wave of goodwill and, after Villanueva, relief. Restoring public faith is a good next step, but that will mean not merely restoring the Sheriff’s Department, but transforming the jail-centered organization of decades past into a modern and responsible component of a broader public safety and care-oriented county system.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.